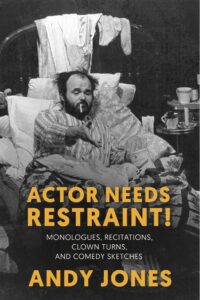

“In all the shows, I’m wanting something to happen”: Andy Jones releases a theatrical collection

January 2025

Congratulations on your new book, Actor Needs Restraint! Monologues, Recitations, Clown Turns and Comedy Sketches. (I won’t spoil the inspiration for the title.) The scripts (Out of The Bin, King o’ Fun, An Evening With Uncle Val) as you present them here are so thorough: the precise dialogue, the extensive and descriptive stage directions, the meticulous notes on props, set pieces, and different production histories.

It was all the instructions that took so long.

You watched videos of those productions so you could be so specific – down to the numbers of ‘ha’s in your ‘hahahahas’.

Also I didn’t know there was videotape of Out of the Bin until after I had done almost everything. After I came back from Toronto I did a benefit for the Hall, I did five nights and Mike Jones and Jim Rillie filmed that. So then I changed a few things because of that. But it took a long time.

How did you choose these scripts for this book?

They had the least number of graphics. I would like to have done the first three (chronologically), but some of them were very graphic-dependent. I wondered if I could describe them – but it will be fun to have them, some of them are quite funny.

It makes a nice arc of your age though, young man, middle age, Uncle Val – I didn’t realize how young you were when you first did Uncle Val.

Uncle Val, when I very first started, it was 1978. I was only 30. I’d just met Francis Colbert, the summer before that, at, it was called The Good Entertainment Festival I think, and it was in Killdevil, on the west coast of Newfoundland, and that’s where I saw Francis.

I’m struck by how often you talk to the audience, and you have a very specific reason why you’re talking to the audience. You’re working out some ideas. And you give the audience a reason to be there.

I always say my name and I always say my age. I am definitely talking to the audience. I try to make up a formula, I try to pretend that it’s scientific, or that it’s a Royal Commission on Reality. I kind of do that with all the shows, that I’m wanting something to happen. I haven’t really analyzed this properly. I go that route almost every show. But every show you do in the world you want people to understand people in the world, this is one person’s story.

The opening of Out of The Bin, I was just right in front of the audience, that’s a real clown turn, to me, that’s pure clown being in the bed, and not having the show together, and talking to the audience in real time. Well, this is the show. What do you think so far? Suppose I’ll get any groupies? Yeah, suppose they’ll be lining up. I’d never had the chance to speak on the stage like that. I didn’t have to raise my voice, I was able to just talk. Then I was able to go do some performative things after I got out of the bed, and I tell them this is a retrospective of my first ten years as an actor, so I did my shtick and all that stuff.

Why is that a “clown turn’?

I asked Beni (Malone, of Wonderbolt Circus) about this and I asked Dean and Mimi (of Theatre Smith-Gilmour), I think it’s because it’s silent. It’s not saying a line, and a line, and a line, a lot of it’s about taking your time to go under the bed to take the can of tobacco out, open it up, to take the tobacco out, take the paper, roll the cigarette. Most Newfoundland theatre you’re talking all the time, it’s very rare you’re having these little moments when you’re just doing something a little bit funny. There’s also a lot of what they call lazzi, and lazzi are your special talents that you have, each one is called a lazzo, but they always call it lazzi even if it’s just one, it’s Italian from Commedia dell’ Arte. Like for example my codfish is definitely my own, and no one else does it. I’ve done that ten times, in CODCO, I used to get caught as the codfish and hauled across the stage. That’s a lazzi and that’s my special thing. In the Commedia dell’ Arte, you’d have a piece of lazzi like that, they’d actually leave it in a will to their children. I did the codfish, I did the vomiting, I always did vomiting. I could leave that to (daughter) Marthe in my will, or (granddaughter) Frannie, to do it on stage. I do the eyes (he makes his eyes bulge by putting his glasses in the flesh under his eyes) of the mother in Jack Meets the Cat and the wolf face (makes a scary wolf face) in Uncle Val. There’s a bunch of those in there.

You also frequently indicate that some audience members are Danish, and may need some extra context. Have you been to Denmark?

Years ago, with The Ken Campbell Road Show, 1973-74, and I never forgot it, we went to Aarhus, the second city after Copenhagen, you know that TV show The Bridge? That’s Aarhus. I was just a young guy, I’d been to university but here we were in Denmark and it was a different world, being in England was such a different world, everything seems much more the same now. I couldn’t believe it. We went to a place called Jazzhus Tagskaegget, it was a music venue but they loved having extreme theatre things there too. The next guest after we left was Miles Davis. Everyone spoke English and everyone was really nice to us, so I’ve used that in a couple shows now, oh by the way for the people from Denmark, Gonzaga is a high school.

You give audience members lines to say. And you often give us chocolates.

I get people in the audience to say things. I’d ask them before the show to say a certain line. It’s a very mild version of what a lot of people are doing now. We just came back from Toronto and we saw Big Stuff, and Hook-Up; they must be the best improv group in the world, Bad Dog Theatre. All the comedians we saw were really involving the audience, talking to the audience, building their whole act around what the audience says. I think it’s a big movement or a big thing that’s happening. And I did that, but I didn’t have very many people. What I think was a very good moment in that clown piece, is where I roll a cigarette and I say Anybody got a light? Of course in those days, everybody smoked, so anybody got a light, and they’d throw a box of matches, and of course it would go on the floor, and I’d go, anybody else got a light? And it always got a huge laugh. Sometimes it took ten boxes of matches or lighters getting thrown at me by the time I finally got one on the bed. I had a match just in case but it never went there. It always, always worked. It was lots of fun. Then I gave them a chocolate. People had to come down and get the chocolate, pick it up.

In your book you write: “these short forms are my beat.”

Everything in me comes in sketches. Except for the last show (Don’t Give Up On Me, Dad), that was about Louis – but I look back at everything I’ve done since my last show and find something in it. You have a concept. And I always usually have one foolish theory based in my foolish version of modern physics. Every single part of all three shows is divided into sketches.

Are you switching from being a comedian to being an actor, or are you smooshing those together? Because I would say – you’re an actor.

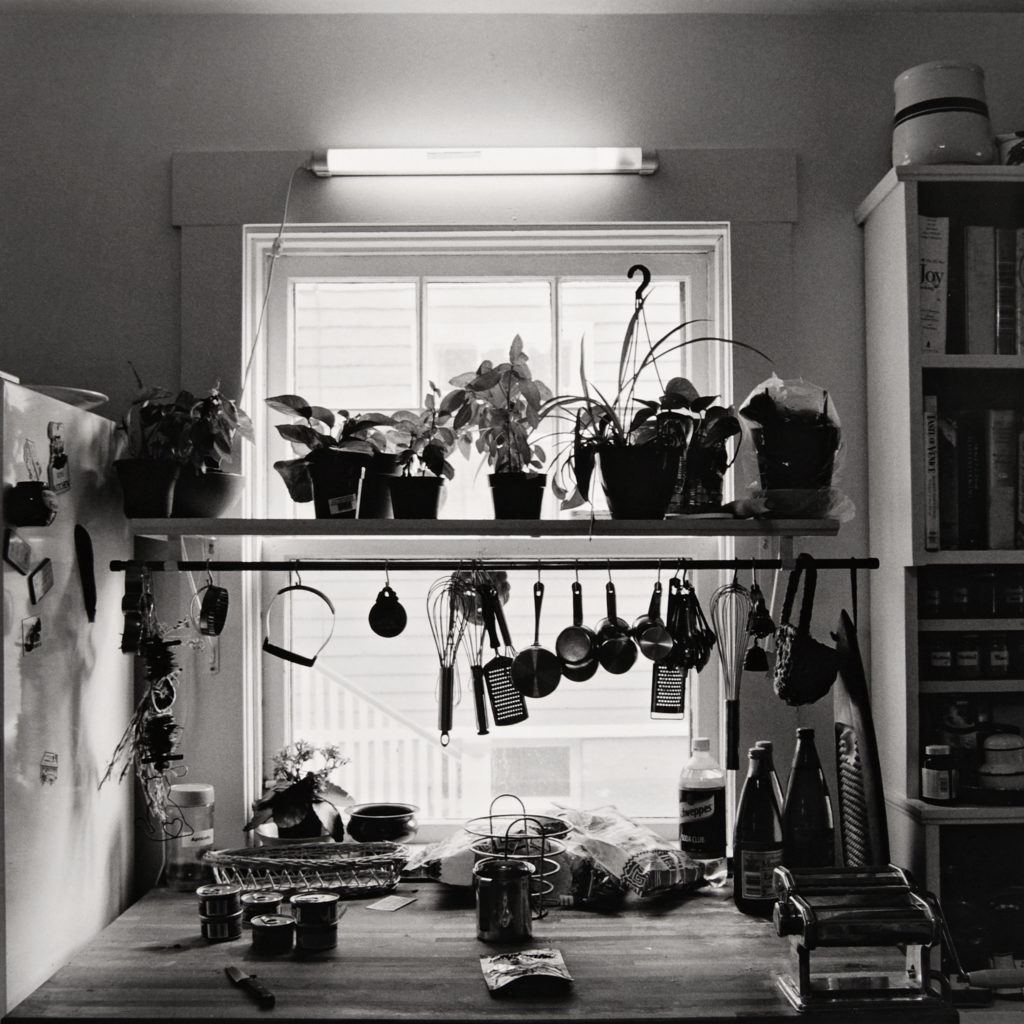

Sometimes inside a sketch I’m an actor. The opening of Out of The Bin is a clown turn, lying in bed going oh my Jesus, ohh, and then nothing, nothing, and then oh my Jesus. You’re obviously performing, it’s performative, it’s not a Fourth Wall, but it’s not (he ‘acts’ oh my Jesus to show the difference). That’s acting, here’s a guy who’s depressed, but I’m not really depressed, I’m playing up the depression, I say it’s arts-related despair, and I’m 35 years old and I got no money and no youngsters. That’s why it took so long to make that set, you couldn’t just throw everything on the set, you had to layer, when we toured people would say I can do that, but no, the magazines had to be laid down how they would be laid down, a bit of clothing here a bit of clothing there, it’s not a complete mess, it’s built up. We weren’t trying to make it look messy. And I literally was able to say, this is a retrospective of my whole career, I’m doing all my stuff. That was the real conceit of the evening, hey it’s been ten years, do you remember this, do you remember that? I’d get in the bed, I’d get out of the bed, in the end all the characters are in bed together. Then in the second half I’m in my apartment and I realize the audience is there. It’s very simple, the actor realizes the audience is there. And any time I want I can refer to a sketch and where it came from.

Is it easy to organize these series of sketches?

No. And often it doesn’t work. It really doesn’t work. I remember telling (director) Charlie (Tomlinson), I don’t know Charlie why this sketch is there, I’m just putting it there. I like a blackboard, it’s partially a lecture, it’s a classroom thing. That made such an impression to me, being in school, I didn’t ever leave it behind, I’m still in the classroom, the chalk dust and the humour and how much we made fun of the teachers. They were specially sent by God to stand in front of you every day for nine months and to squeeze every drop of comedy from what they did.

Jones’ next collection will include the plays Still Alive, To The Wall, and Don’t Give Up On Me Dad. In May, Jones will be the Ambassador for the NL Sketch Fest. He is also cast in This Side of the Grave, a new 6×10 minute web series filming in the St John’s area this coming summer, directed by Catharine Parke. “We are so honoured to have this legend of both theatre and film as a key member of our cast,” Parke shared in an email. Other cast members include Emma Hewitt, Mark Power, Santiago Guzmán, and Jill Kennedy. “We applied for web series production funding through the Independent Production Fund and the Canada Media Fund and were over the moon when This Side of the Grave was selected.”

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.