MAKING NEWFOUNDLAND’S SOLDIERS: THE NEWFOUNDLAND REGIMENT, THE BRITISH ARMY, AND TRAINING FOR BATTLE, 1914-1915

March 2019

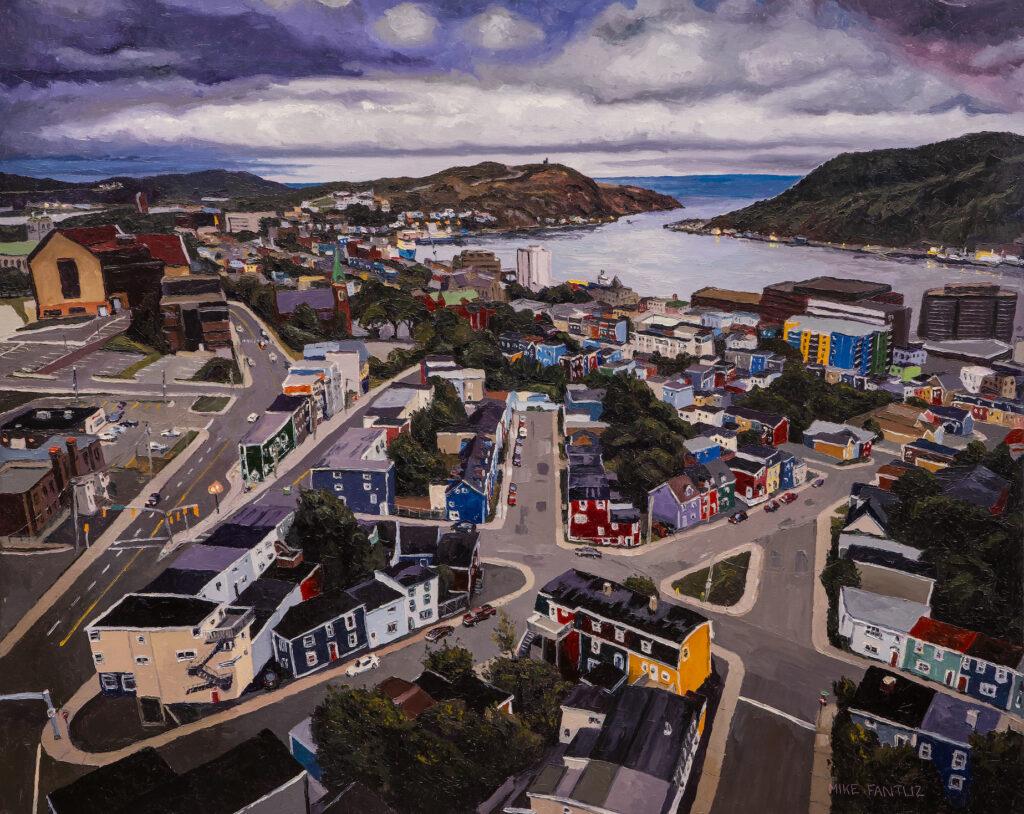

In early October 1914, the first contingent of the recently-raised Newfoundland Regiment left St John’s for England on SS Florizel, after having undergone a month of basic training at a makeshift camp at Pleasantville. There they had begun their transition from civilian volunteers to battle-ready soldiers through a program of training that included drill, physical training, route marches, skirmishing, and rifle practice. While the men of the regiment displayed a very high level of enthusiasm that would serve them well in the struggles to come, the rudimentary nature of the facilities at Pleasantville, combined with a dearth of professional military instructors, meant that the bulk of their training would have to take place overseas.

While Part I of this study (published in NQ fall 2018) dealt with the Newfoundland Regiment’s initial period of training at Pleasantville, this concluding installment will cover their training experiences from their arrival in the United Kingdom to their deployment to the battlefield. In that period, the Newfoundland Regiment would go from being a raw but eager collection of amateurs to a well-trained military unit ready to take its place alongside British regular troops. But despite the cohesiveness and efficiency which they achieved during their first year in uniform, and the honing of their military skills in the Gallipoli campaign, the Newfoundlanders were still inadequately prepared for the large-scale industrial warfare they would encounter on their arrival in the trenches of Picardy in 1916. The fault, though, lay not in any specific failings of the Newfoundland Regiment, but in the structural inadequacies of the British Army as a whole. By 1917, the Regiment would prove decisively that it could equal the performance of any British infantry battalion.

Training in the United Kingdom

Once the Newfoundland Regiment reached Britain in October 1914, they were able to train for the first time with up-to-date equipment. The soldiers were issued with Canadian Ross rifles and British web equipment,1 but much of the training they received still consisted of the basics they had begun at Pleasantville. The main difference was that their instructors were more experienced, and the training was much more “realistic” than what they had been through prior to leaving St John’s. Most of the men appreciated the much higher standard of training provided by professional instructors, though some of the more sensitive souls in the Regiment were horrified at the foul language used by British Army NCOs.2

The first destination for the Newfoundland Regiment in the United Kingdom was Salisbury Plain, where they were attached temporarily to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. There, they resumed their regimen of basic infantry training. Conditions on the Plain, which was normally used only as a summer training ground, were almost unbearably miserable during a particularly cold and wet fall. Owen Steele complained in early December that the men of the Regiment had “seen more mud than we have ever seen before.”3 Having to train all day in ankle-deep mud, and then appear on parade the next morning in spotless puttees and well-polished boots, was, to say the least, a bit of a challenge, and after seven weeks the men of the Regiment were happy to learn that they would be moving elsewhere.4

Newfoundland Regiment on Salisbury Plain, with Ross rifles, 1914.

Courtesy of Centre for Newfoundland Studies.

In early December, the Regiment was posted to barracks at Fort George, in the Scottish Highlands, where they spent ten weeks undergoing intensive training. Even the rigors of a Scottish winter came as a relief after the misery of Salisbury Plain. The men of the Regiment were very impressed with the facilities at Fort George, an 18th-century star fort which served as the regimental depot for the Seaforth Highlanders. Excellent musketry ranges were close at hand, as were rolling hills ideal for skirmishing practice, and an obstacle course for advanced physical training.5

Courtesy of The Rooms.

Most of the Regiment’s training in Britain was supervised by Lieutenant-Colonel Reginald de Hardwick Burton, a retired officer of the Middlesex Regiment, who was appointed to command the Regiment in November 1914. Burton was a stereotypical “dug-out” who believed in old-fashioned training methods, with a heavy focus on parade square drill and a fondness for long and grueling route marches.6 Once ensconced in Scotland, the men were forced to march as much as 20 to 25 miles in a day with full equipment. And for a British infantryman in 1914, “full equipment” tipped the scales at more than 60 pounds. By way of comparison, that was more weight than was carried by a typical medieval knight in full suit of plate armour.7 Many men of the Newfoundland Regiment, like their British counterparts, found these long route marches arduous and tiresome.8

Their arrival in Britain also introduced the Newfoundlanders to other elements of infantry training. One of these was bayonet training, which involved learning techniques of thrusting and parrying, as well as practicing bayonet attacks against dummies made from sacks filled with straw. While the Regiment had done some rudimentary “bayonet drills” at Pleasantville, it was not until they arrived in Britain that they could train with actual bayonets. Infantry Training 1914 emphasized the importance of bayonet training and the need to develop an aggressive approach to its use. British Army leaders, like their counterparts in other armies, tended to be big believers in the decisive power of bayonet attacks and sought to imbue men with “the spirit of the bayonet.”9 That clearly appears to have worked in the case of the Newfoundlanders. After one particularly vigorous session of bayonet drills on an obstacle course in Scotland, Private Frank Lind noted that “we often regret it is not Germans who are there instead of sacks.”10

Soldiers also had to be trained in the digging of trenches, an activity valued in the pre-war army not only for its tactical aspect but for its contribution to physical fitness.11 It was not a particularly popular part of the training regimen, as soldiers tended to view trench-digging practice as a form of drudgery. Despite the importance of trenches in the AngloBoer War, British pre-war training manuals dealt with their construction only in the most rudimentary fashion. Given that the training manuals in use in 1914 placed so much stress on offensive action, practice in constructing trenches was not of primary concern. They were considered to be only a temporary expedient, as an adjunct to offensive action. Hence little or no thought was given to the issue of the longterm inhabitability of trenches, in terms of water drainage and other such factors.12

The emergence of trench warfare in France and Belgium in late 1914 led to a greater emphasis on trenches in infantry training. The trench networks that developed on the Western Front were far more elaborate in their construction than anything envisioned in pre-war times, so gradually more effort was devoted to practice in the siting, digging, and defending of trenches.13 By the spring of 1915 the men of the Newfoundland Regiment found that they were spending an increasing amount of time practicing trench-digging.14

All the basic skills of a soldier had to be practiced until they became “second nature” to the men. Once these basics were mastered, soldiers moved on to more advanced training, including techniques of fire and movement, the use of ground to conceal movement from the enemy, patrolling, and moving by night.15 As well, selected soldiers were given advanced training in weapons like machine guns and Mills bombs (grenades). Specialized training was also provided to those soldiers selected for the roles of signalers and pioneers. The Regiment’s officers had to attend special courses as well, including instruction on the use of their swords in combat.16 This despite the fact that by late 1914 swords were no longer worn on the front lines, as sword-carrying officers made attractive targets for enemy snipers.17

To many of Newfoundland’s volunteers, the length of their training period in Britain came as a cruel shock, as most of them had joined up expecting to see almost immediate action. The months spent in Scotland were hard on the morale of the Newfoundlanders, who were increasingly anxious to get to the front. By February 1915, soldiers of the Regiment were expressing frustration at having to remain in the United Kingdom.18 Almost half of all disciplinary infractions committed by soldiers of the Regiment during the war occurred in Britain prior to their deployment to the Middle East.19 The full year spent on training the Newfoundland Regiment was hardly unique; none of the units of “Kitchener’s Army” left the United Kingdom for at least ten months after their training began.20

The Final Preparations

In May 1915, the Regiment moved to Stobs Camp in Scotland, where for the first time it engaged in training exercises with a British infantry brigade. It was also at Stobs Camp that the men of the Regiment, who up to this point had been using Canadian Ross rifles, were finally able to train with the short Lee Enfield rifles that they would use in battle. By this time, the Regiment’s training period was nearly complete and the men were, in the words of Lind, “hard as nails.”21

The beginning of August saw another move, this time to Aldershot to put the finishing touches on their preparation for the front. There they engaged in large-scale exercises which included artillery and other arms. On August 12 came the big day when the Newfoundlanders were inspected by Lord Kitchener, who announced that they would soon depart for the Dardanelles campaign. Eight days later they were on a troopship bound for the Middle East, and the journey begun at Pleasantville entered a new and much more dangerous phase.22 On an ominous note, one of the last lectures received by the men of the Regiment before leaving Aldershot was on the use of the newly-invented gas mask.23

The Regiment underwent one final round of preparatory training in Egypt, consisting mainly of route marches to acclimatize the men to hot Mediterranean conditions. The Newfoundlanders found marching in the blistering desert heat to be one of the most difficult parts of their entire training period.24 Ironically, the greatest challenges of the Gallipoli campaign in terms of climate involved coping with frostbite and hypothermia as winter set in.25

So how effective was the training that the Newfoundland Regiment underwent before going into battle? The answer seems to be as effective as was likely under the circumstances. Despite the makeshift nature of their early training and the lack of military experience within the unit, the Newfoundlanders were ultimately able to keep up with the British regular units with whom they were brigaded in the 29th Division, and with whom they took their place in the trenches at Gallipoli in September 1915. After a slightly shaky start, the Newfoundland Regiment gained a reputation for enthusiasm and efficiency that led to them being chosen for the vital task of covering the withdrawal from Suvla Bay.26

Yet despite the success of their training, the Regiment was not well prepared for what faced them in 1916 when they were transferred to the Western Front. That problem, however, was not peculiar to the Newfoundland Regiment. In fact, it applied to the entire British Army, and was the result of the army’s shortcomings when it came to preparing for a major continental war.

Drawbacks of the British Training System

Newfoundland Regiment marching in Britain, 1915.

Courtesy of The Rooms.

One major shortcoming of the British system was that infantry soldiers got very little training in cooperating with other arms, particularly with artillery, before arriving at the front. While the Field Service Regulations of 1909 stressed the importance of close coordination between different arms, noting that “the full power of an army can be exerted only when all its parts act in close combination,” it said precious little about exactly how coordination between arms was to be achieved.27 The problem of inter-arms cooperation would plague the British Army through the first few years of the First World War. The inability to properly coordinate the actions of infantry and artillery units was a major contributing factor to the catastrophic death toll during failed attacks at Beaumont-Hamel and elsewhere on July 1, 1916. This was in stark contrast to the French Army, which had considerable success in attacking on the first day of the battle of the Somme by employing a well-timed artillery barrage.28

The main cause of the problem of inter-arms cooperation was that the British Army of 1914 was designed primarily to fight colonial wars in faraway places, and its decentralized regimental system provided great tactical flexibility in the diverse circumstances of such “little wars.” In some ways, it was less a cohesive army than a collection of regiments, each with its own identity, traditions, and methods; it was thus not particularly well designed for a large-scale war on the European continent. Larger formations tended only to be wartime expedients, at least until 1909, when the Army in the United Kingdom was first organized into permanent divisions.29

The decentralization of the Army carried over into military training, where the 227-man company served as “the principal training unit in the battalion.”30 This was in stark contrast to the German and French armies, which spent much time on large-scale exercises. In the United Kingdom, large divisional level exercises did not begin until after 1909, and even then they were held only once a year, mostly with understrength units. Overseas, where most British soldiers were stationed in peacetime, there was no training above the battalion level.31 This carried over into the war, when, as was the case in the Newfoundland Regiment at Aldershot in August 1915, training with a full division was limited to barely a week at the very end of their training period.

Britain’s lack of such large-scale training impacted not only units but the men who commanded them. All British generals in 1914 had experience commanding troops in battle, and all those in high command positions were men who had proven their competence and efficiency in the Anglo-Boer war. But only three of them had ever commanded at a level higher than that of an 18,000-man division, and that was only during brief periods of training on Salisbury Plain. Thus at the start of the war, British commanders had to learn to control formations much larger than any they had previously worked with, and to do so while fighting was going on.32

While on the one hand British Army training was deficient in the tactical handling of large formations, it was also lacking when it came to small-scale platoon tactics. The Field Service Regulations of 1909 noted the importance of small-unit tactics in modern warfare, but at the start of the First World War, small units themselves existed in only the most embryonic form. While 40-man platoons existed as administrative entities, they had not fully evolved a clear tactical purpose by 1914. The only discussion of platoons in Infantry Training 1914 pertained to close-order drill.33 The workings of small-unit tactics had to be learned by British troops while fighting on the Western Front.

Moreover, all British infantry training at the start of the war was geared toward preparation for mobile warfare; it was simply assumed that the main emphasis in modern war would be on rapid manouevre. British infantrymen in 1914 were very proficient in field craft, the use of ground, fire and movement, and executing flanking attacks. These skills were passed on through contemporary training regimes to the new units raised in the early months of the war, including the Newfoundland Regiment. While the fire and movement tactics practiced by British forces in 1914 had proven successful in the Anglo-Boer War, they fell short against well-entrenched German troops equipped with plentiful machine guns and heavy artillery.34 The first British Army manual dedicated to teaching the methods of trench warfare did not appear until the spring of 1916.35 And not until 1917 did the training of new recruits really begin to reflect the realities of war on the Western Front.36

Conclusion

Despite their long period of preparation, the Newfoundland Regiment’s first major action on the western front, the attack on Beaumont-Hamel on the first day of the battle of the Somme, was an unmitigated disaster, in which nearly 700 men of the Regiment were killed, missing, or wounded without any gains being made. The training deficiencies that contributed to both the high death toll and the failure to capture objectives on July 1, 1916 were not at all specific to the Regiment; they reflected the British Army’s structural failings in preparing for both inter-arms cooperation and small-unit tactics. Numerous British infantry battalions, including regular and territorial units, also suffered very high casualties in failed attacks on the German trench lines.37 On the other hand, French infantry units which took part in the attack enjoyed more success at a much lower cost, a reflection of the French Army’s overall better preparation for largescale warfare, particularly when it came to coordination between artillery and infantry.38

Training, though, did not end once a unit was deployed to the front. In fact, British Army units on the Western Front spent considerably more time in training than they did in the trenches. Between short stretches on the front lines, soldiers spent weeks in rear areas, keeping their basic military skills well-honed and learning new techniques for dealing with a constantly evolving tactical situation.39 The Newfoundland Regiment would spend its time on the Western Front in an ongoing process of learning and adapting, with veteran soldiers passing on their skills to a constant stream of fresh reinforcements.

Any notion that the Newfoundlanders might not be up to the challenges of the modern battlefield was put to rest on October 12, 1916, when the Regiment took part in an attack on German lines at Gueudecourt. Advancing behind a well-coordinated creeping artillery barrage, a technique borrowed from the French, the Regiment was the only British unit which managed to capture all of its objectives in the attack.40 Gueudecourt turned out to be only the first of a series of impressive though costly successes by the Newfoundland Regiment on the Western Front, which won them numerous accolades from British generals and resulted in the Regiment receiving the designation “Royal” in December 1917.41 By the time of its final action at the battle of Courtrai in October 1918, in which the Regiment again enjoyed notable success, it was easily the equal of any unit in the British Army. Newfoundland’s soldiers had come a long way since their very humble start on the cricket field at Pleasantville.