RESURRECTING THE GREAT AUK

BY Drew Brown

April 2018

The Woolly Mammoth is often raised as a prime candidate for de-extinction: that is, the re-creation of an extinct species through a close genetic replica. The new mammoths would be an Asian elephant-mammoth hybrid, and its first few generations would never know the wild. While this kind of necromantic biotech is more speculative than real, in principle it can be done.

The prospect of mammoths thundering again across the Siberian steppes is thrilling. But if we’re getting into the business of resurrecting the genetically dead, we should spare a thought for the poor Great Auk.

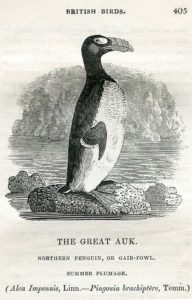

Great Auk, Thomas Bewick , 1804

The Great Auk was a large and flightless seabird that made its home among the inhospitable rocks of the North Atlantic. One of its largest breeding grounds was Funk Island, 37 miles off the northeast coast of Newfoundland. They were two and a half feet tall and weighed as much as a well-fed toddler. Marvelously, this “penguin” was singularly unafraid of human beings. For its courage, the species was rewarded with a spectacularly grisly demise.

Not only was the Great Auk an excellent source of fresh meat and bait for transatlantic sailors, but it also had fine, soft down ideal for the feathered pillows and cushions fashionable in Europe. Its body was covered in a thick layer of fat and oil good for all manner of fuel, and its eggs were so delectable that the Beothuk canoed 60 kilometres out to sea in search of the big bird’s nests. When Sir Richard Whitbourne wrote in 1622 that it was “as if God had made the innocency of so poore a creature to become such an admirable instrument for the sustenance of man,” he could not have foreseen that this providential treasure would be squandered in less than two hundred years.

In its 18th century heyday, trappers looking to get in on the Great Auk gravy would camp all summer on the foul-smelling Funk Island. The pliable pseudo-penguins were corralled around with makeshift rock walls and driven into boiling cauldrons of water. The birds had to be boiled first in order to pluck the feathers, and because there were no trees on the island most fires were lit using the fatty carcasses of other Great Auks. It did not take long to burn through the fatally sociable birds. The last of Newfoundland’s Great Auks was boiled on a pyre of his cousin’s corpses sometime around 1800, and the species was extinct worldwide before 1850. William Blake’s “dark Satanic mills” pale before the columns of crematory fire that lit up Funk Island like a ghastly, hellish lighthouse.

It is easy to read the story of the Great Auk as an early omen that the hunger of human society might stretch and smash the limits of nature. This is true but incomplete. Time and distance make it easy to throw judgement on the men who did that work. It is harder to put ourselves on those schooners bound for Funk, ten millennia of brine and birdshit stinking in your nostrils over the hunger pangs, praying that this seasonal slog of blood and grease and soggy feathers will get your family through the winter. As Dr. Marx likes to remind us: men indeed make history, but rarely on the terms of their own making.

The Great Auk got a raw deal. Setting its cloned Razorbill-hybrid progeny down on Funk Island as an act of atonement is a tempting proposition. Easing our collective guilt aside, a resurrected Auk could be an economic boon. Every cove and tickle would put in an ACOA grant to host a penguin hatchery. Newfoundland and Labrador would become the world’s leading exporter of child-sized emotional support birds. One less piece of karmic debris to discharge and one less crime to confess to Jesus when He comes back in anger to boil away the seas.

Then again, necromancy might be a touch too ambitious. Better to leave the bones of the dead to their final rest at Funk until we fully absorb their lesson. What is the real cost of a feather pillow? A ytterbium smartphone? A bag of shrimp, a candy bar, a banana gently ripening on the grocery store shelf? Physician, heal thyself. So long as the grind of global production keeps us anchored to a funeral pyre somewhere in a far-flung corner of the world, I beg you: the world is not yet pure. Let the Great Auk sleep.