Thirteen Ways of Looking at an Iceberg

August 2017

1

It is a cluster of Alpine mountains in miniature: peaks, precipices, slopes and gorges, a wondrous multitude of shining things, imposing and sublime. I’ve been reading After Icebergs with a Painter, Rev. Louis L. Noble’s imaginative travelogue from a voyage around Newfoundland in 1859. It’s like following a jet-setting paparazzo’s Instagram, day after day of swaggering selfies and impossibly scenic landscapes – except instead of celebrity photos, it’s full of nineteenth-century prose portraits of icebergs. Our game, for once, is the wandering alp of the waves; our wilderness, the ocean; our steed, the winged vessel; our arms, the pencil and the pen.

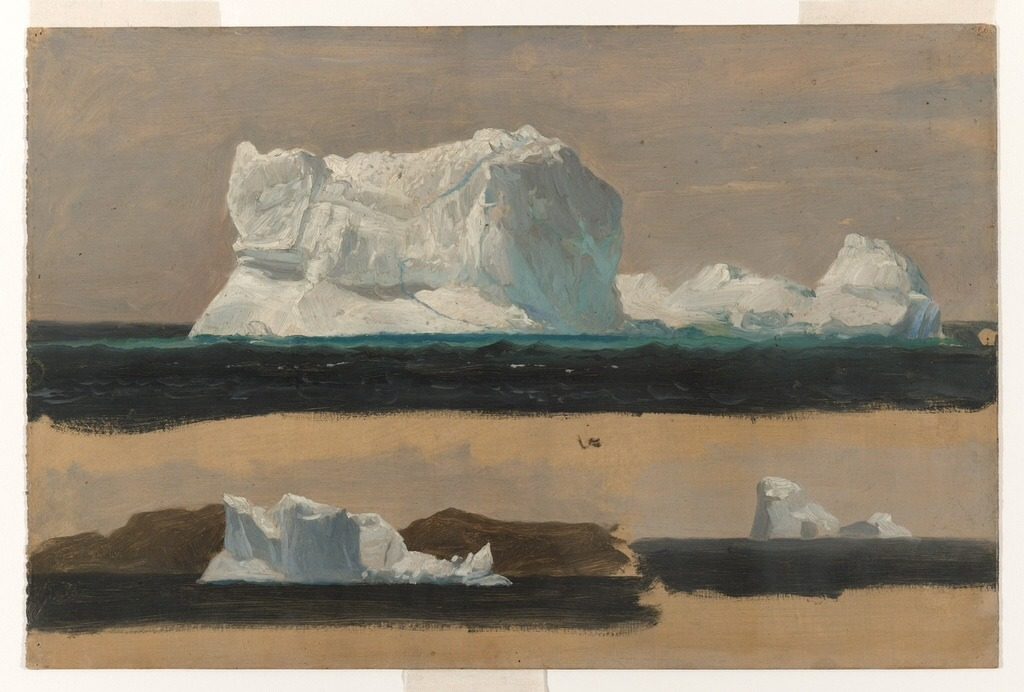

The painter in the book’s title is Noble’s friend Frederic Edwin Church, remembered today for his lush, panoramic landscapes painted in oil. Noble’s writing is similarly melodramatic. Fashioned by those fingers that wrought the glittering fabrics of the upper deep, and launched upon those adamantine ways into Arctic seas, how beautiful, how strong and terrible!

When I take a break from the book and look out my window to find a late-July iceberg lingering off Cape Spear, it’s hard to reconcile its simple white speck with Noble’s marble castles and glimmering mountains. So I head up Signal Hill for a slightly closer look.

Frederic Edwin Church – Iceberg Studies (Twillingate, Newfoundland) (1859)

2

There is something in a mountain ramble that pays for all warmth and fatigue. I often walk the North Head Trail, which starts at the end of the Battery and winds its way up to Cabot Tower. On the rougher parts of the path, as I clomp over boulders that jut from the hillside like broken bones, it’s possible to imagine walking Signal Hill a century-and-a-half ago, before the paved road and the parking lot, before the Parks Canada signs and the roar of motorcycles. I was going to write “before the tourists” – but of course even Noble and Church, visiting in 1859, were quintessential sightseers. Noble wrote:

We set off for Signal Hill, the grand observatory of the country… little rills rattled by, paths wound among rocky notches and grassy chasms, and led out to dizzy “over-looks” and “short-offs.” The town with its thousand smokes sat in a kind of amphitheatre… below us were the fishing-flakes, covered with spruce boughs. We struck into a fine military road, and passed spacious stone barracks, soldiers and soldiers’ families, goats and little gardens.

Goats! I always feel a little goat-like and giddy after picking my way to the ragged edge of the North Head. As I crest the hill, there’s the berg – poised like a silver coin, as if it’s about to slip into the wide slot of the horizon with a satisfying clink.

3

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

In Wallace Stevens’s “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” each stanza of the poem is inhabited – almost haunted – by the blackbird’s oblique presence. From my perch on the North Head the berg is mesmeric, its sharp brightness like a lick of flame, and I wonder if I could write “Thirteen Ways of Looking at an Iceberg.” When the blackbird flew out of sight, / It marked the edge / Of one of many circles, mused Stevens, and I imagine the iceberg as the pointy end of a drawing compass, pinned on the horizon’s arc.

Perhaps the compass’s pencil-end is in the hand of Noble, 158 years ago, as his ship transcribes a wary circle around his quarry. We dart off a mile or more from our right path in order to bring a small berg between us and the sun… all drips with silvery water as if newly risen from the deep. In the pure, white mass there is the suspicion of green.

Frederic Edwin Church – The Iceberg (1891)

4

It was already late afternoon when I left home and now, with my back to Signal Hill, the North Head’s brawny shadow stretches over the water towards the distant berg. The iceberg seems to quiver in its stillness, as if at any moment it might flee, scurrying for the shelter of Blackhead or Freshwater Bay. It stares back at me like the eye of a wild animal, as if I’ve stepped around a bend and startled a moose.

5

The iceberg gleams like the hilt of a sword, its blade sheathed in seawater. Beneath my feet, pale veins of quartz hint at mineral deposits slashing through the hillside. I look up at the lighthouse at Cape Spear and imagine it extending underground as solidly as the ice does underwater, its spiral staircase drilled into the headland twenty storeys deep.

6

I squint at the small white rectangle as if the iceberg is a label in an art gallery, seen from across the room. Maybe, if I could somehow stride across the ocean’s crumpled blue carpet, it could tell me who painted the elegant, sunlit landscape of Cape Spear beside it.

7

For Noble and Church, who hired a ship to get as close as they dared, icebergs were masterpieces meant to be seen up close. Monstrous, mighty, multifaceted, they lurch to life in Noble’s ecstatic testimony. The water streams down in all directions, glistening in the light like molten glass. Veins of gem-like transparency, blue as sapphire, obliquely cross the opaque white of the prodigious mass… all is perishable as a cloud, and charged with awful peril.

8

If I lean back and unfocus my eyes, attempting to take in the entirety of the horizon, the iceberg becomes a mote of dust lodged in the great eyeball of Earth. A dark cloudbank to the north slowly closes like a vast eyelid, as if, after the long blink of nightfall, the iceberg will be gone, cleared away like a tear.

9

After staring for a while, the ice dazzles my eyes. It freezes my brain, like guzzling a cold drink too quickly on a hot day. The marvellous beauty of these ices prompts one to speak in language that sounds extravagant. Had our forefathers lived among these wonders, we should have had a language better fitted to describe them…. I am quite tired of these words: emerald, pea-green, pearl, sea-shells, crystal, porcelain and sapphire, ivory, marble and alabaster, snowy and rosy, Alps, cathedrals, towers, pinnacles, domes and spires….

Frederic Edwin Church – The Icebergs (1861)

10

The iceberg plays the grooves of my brain like the diamond needle of a record player. I remember seeing icebergs near Catalina last summer, two of them bright as a pair of new sneakers. April White and I wrote a song about them:

Icebergs shaped like shoes!

Oh, if only I could choose

to make my feet the skippers

of these transatlantic slippers,

I’d stroll the ocean blues…

11

Looking for metaphors in icebergs is a little like finding shapes in clouds. Maybe it’s more useful to ask: what do icebergs do? Icebergs, to the imaginative soul, have a kind of individuality and life, wrote Noble. They startle, frighten, awe; they astonish, excite, amuse, delight and fascinate.

To which I’ll add: they drift, they gambol, they bask. They glisten, gleam, glint; they pack sunlight into snowballs and fling them at your face. They are a favourite playground of the lines, surfaces and shapes of the whole world, the heavens above, the earth and the waters under. They splash and drip, gurgle and fizzle, surge and churn, sputter and clink. They thunder and roar, shatter and collapse, make waves, sink ships. These are the poet’s and the painter’s fields, more than they are the fields of the mere naturalist. They jettison bits and pieces of themselves, become flotsam and jetsam, jazzing up landwashes and jars of whisky. They have a daily experience, and a current history more remarkable now than ever. They ferry messages from the past and future. They founder and languish, melt and diminish, vanish.

12

They mimic all the styles of the architecture upon earth; rather, all styles of architecture may be said to imitate them, inasmuch as they were floating here in what we please to call Greek and Gothic forms long before Greek or Goth were in existence.

Perhaps, instead of comparing icebergs to things, I should be comparing things to icebergs. What if I walk home to find my house half the size it was when I left, slumping into the sunny backyard? What if the entire island is an iceberg adrift in the North Atlantic, and might rumble and roll over at any moment?

Frederic Edwin Church – Icebergs (1863)

13

Perhaps the iceberg came here to look and listen, too. Perhaps it’s sharpened to a point underwater, scribbling on the seafloor, sketching a subaquatic portrait of Cape Spear or Signal Hill. I imagine myself from the iceberg’s point of view, a tiny dot against pale pink sandstone.

And, after all, what is it? It is simply shadow. All the grand façade is one shadow, with a rim of splendor like liquid gold leaf or yellow flame, but in those depressions is a deeper shadow. Shadow under shadow, dove-colored and blue. Thus there seems to be drifting about, in the hollow lurking-places of the dead white, a colored atmosphere, the warmth, softness, and delicate beauty of which no mind can think of words to express…. You can feel it, after you have forgotten what its complexion precisely is, and from that emotion you may come to remember it. You would remember nothing more beautiful.