Good Country

BY Sharon Bala

January 2018

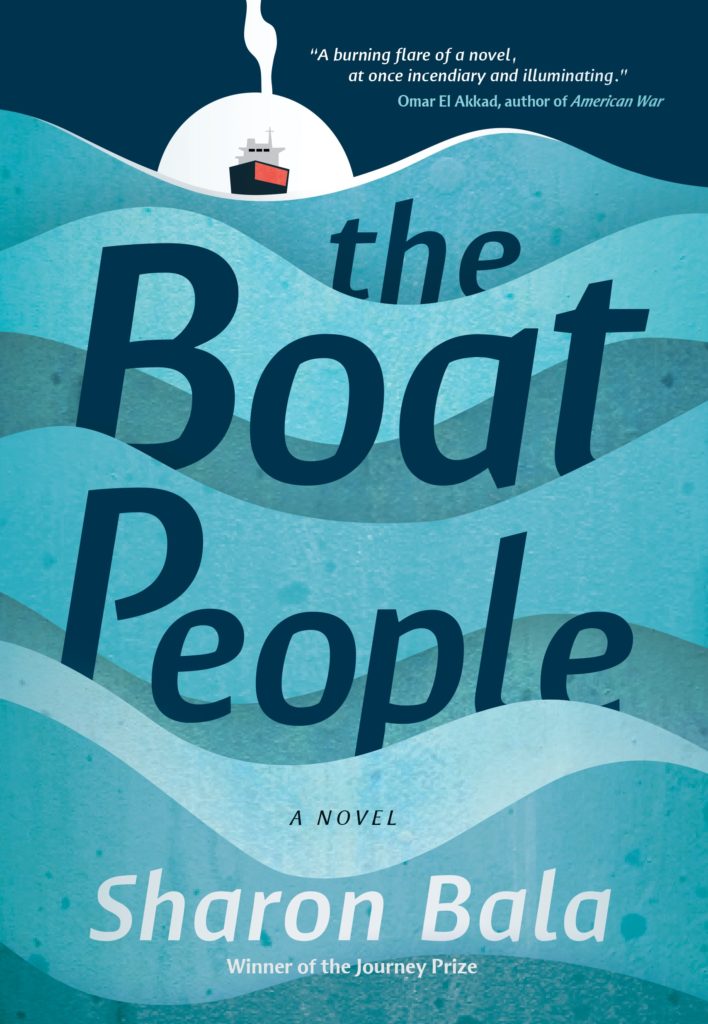

Sharon Bala’s debut novel, The Boat People, exploring the experiences of a father and his son arriving in Canada on a migrant boat from Sri Lanka, was published this month. The St. John’s launch is taking place at Eastern Edge Gallery, on Thursday, January 18th, at 7:30.

On a rainy afternoon in September 2010, I stopped in at Halifax’s Pier 21. Once a bustling terminal, this seaport welcomed 1.5 million immigrants and refugees between 1928 and 1971, roughly one in every five new Canadians. Today it houses the Canadian Museum of Immigration and showcases the hardship and hope of all those who arrived looking for a new start. Announcing the museum’s creation a year earlier, then-Prime Minister Stephen Harper declared: “Pier 21 symbolizes who we are, a nation of newcomers bonded together by a common quest for freedom, opportunity, and democracy.”

A nation of newcomers. I wandered around, mesmerized by the exhibits documenting new arrivals: Cold War-era Hungarian refugees, the Vietnamese Boat People, WWII child evacuees from Britain, Holocaust survivors, and many, many others. I saw archival photographs of crowds packed on boats and heard their testimony of being seasick during terrifying ocean crossings.

I had recently returned to Canada after a year living overseas and was going through a phase where I felt unusually patriotic. The country was still revelling in the afterglow of the Vancouver Olympics which, no doubt, contributed to my feelings. It wasn’t pride exactly, more like a recognition of my own good fortune. To have the right to claim ownership to a vast, safe, rich country is a miracle.

And it’s one I don’t take for granted. My family is from Sri Lanka, a country torn apart by ethnic tension – the majority Sinhalese vs the minority Tamils. My father, a Tamil, has memories of being a child during the riots of the 1950s, in the capital city of Colombo, when the local Hindu priest was set on fire by Buddhist nationalists. From the age of 12, he was plotting his escape.

At Pier 21, I came across this quote, something an anonymous immigration officer told a newly arrived Hungarian refugee: “You have come to a good country. There is room for you here.” This was certainly the case for my family. We immigrated in 1986, in the early years of the Sri Lankan civil war, when Canada’s doors were wide open and a tidal wave of Tamils flooded in.

That same year, Newfoundlanders will remember, 155 Tamils who were found floating in life rafts and rescued off the coast of St Shott’s. Amid the clamour to “send them back,” then-Prime Minister Brian Mulroney stood in front of reporters and declared: “We are not in the business of turning away refugees. If we err, we err on the side of fairness and compassion.”

But Canada has a split personality when it comes to these things. The Komagata Maru (1914). The St Louis (1939). These are ugly chapters in our nation’s history. And in 2010, while I was ambling around Pier 21, another ugly chapter had begun. The MV Sun Sea – a rusty cargo ship bearing nearly five hundred Tamils – had just arrived on the west coast. These refugees – survivors of a brutal 30-year civil war – were being labelled by our government as illegals, queue jumpers, and terrorists. They were thrown into prison, children separated from parents and put into foster care. The news media buzzed with the controversy and judging by the call-in shows, polls, and online comments, the government’s actions were bolstered by popular support.

I was feeling vaguely connected to these asylum-seekers on the opposite end of the country, who could just as easily have been me, but also seeing the drama unfold from a great physical and psychological distance. And I was thinking: My god, what people endure just to come here, to have a shot at all the freedoms and safety I take for granted.

And I was disgusted too, appalled by the national amnesia that allowed us to celebrate our openness and generosity, our common quest for freedom, on one coast while simultaneously slamming the door shut on the other.

That day at Pier 21 struck a chord. Those complicated feelings – of national pride and shame – stayed with me, rattling around deep in my subconscious. I wasn’t a writer then but three years later, when I sat down to draft a novel, the words of that immigration officer returned to me: “You have come to a good country. There is room for you here.”

This was the seed I unwittingly picked up in Halifax and carried home to St John’s. Before plot and character and pacing, before anything else, I had those two sentences, and this notion of the country as a place of continual influx – war brides and war escapees, American slaves seeking freedom via the Underground Railroad, evacuees air lifted out of Kosovo, wave upon wave of new arrivals lapping up on the shore.