ROAM LIKE HOME: JOURNAL ENTRIES FROM A TRIP ACROSS NEWFOUNDLAND

May 2019

The author and her daughter

Photo by Scott Grant, RONiN photography

Travelling across Newfoundland last summer, I put more than 3,500 kilometres on my rental car. That doesn’t include the time spent on foot, aboard boats, or the various other ways I could have marked the time. Like, I could have counted the number of diapers I changed, having taken my (then) 7-month-old daughter in tow for the entire trip. Or I could have logged how many meals of cod I indulged in – I was primarily there to research my forthcoming book about the collapse of the cod fishery and how the province and its people have changed since then. Or I could have attempted to capture the memories I shared with friends and family, having tagged in various folks to join me for road-trips along the way.

All told, June-July 2018 took me from the Avalon to the Burin peninsulas to the north-central coast to western Newfoundland, then to the Northern peninsula and back again. Apart from my book, I documented the trip with journal entries, photographs, and landscape paintings. What follows are some of my favourites.

June 25, 2018

Aquaforte, Avalon Peninsula

A grounded turquoise-trimmed, white fishing vessel is propped upright with wooden stakes. The paint peels on her plywood cabin and hull, which rests on a bed of greenery, mostly mosses and grasses. It’s the kind of hardy, low-lying vegetation one expects out here in the elements at the edge of the Atlantic, even in this sheltered bay. What these sturdy plants lack in height, they make up for in surface area, creeping across and over the bank to the stony beach at the water’s edge. There, every rock is adorned with the jewels of bright bursts of beaded orange seaweed. Competing for colour as they keep one another company are two white-trimmed, red ochre-painted fishing stages. One casts its reflection in the still and shallow bay, granting a flash of colour to the otherwise dull, silty liquid. Back on shore, the weary wooden vessel also keeps company, with a dory, wearier still. The dory’s stem is gaping open and her planks are rotting and gray. Give her a few more years and she’ll sink into her final resting place once and for all.

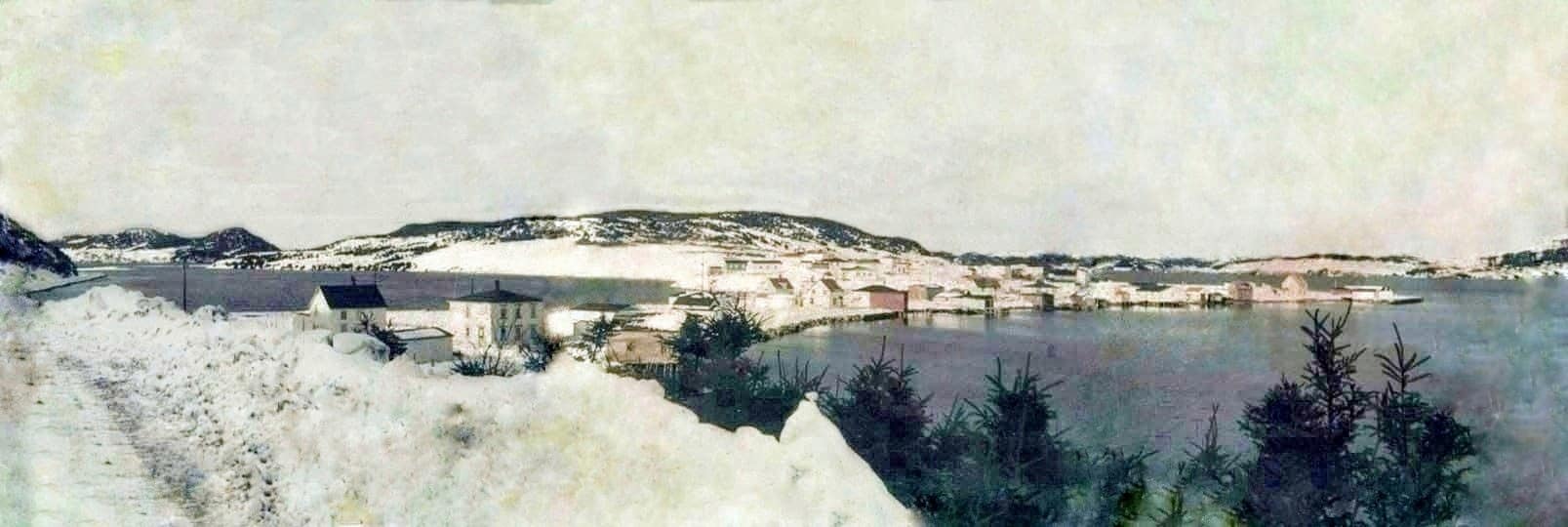

June 29, 2018

Little Bay East, Burin Peninsula

Little Bay East circa 1967-68

Original photo by Lloyd Green

Edited version by Clayton Burton

A nearly 100-year-old house sits on a floodplain, water views from all sides. It’s undergone renovations over the years: six front-facing windows downsized to four smaller ones; wood-clad siding replaced with vinyl; white picket fencing traded in for chain-link. I view the house from the shoulder of the highway, comparing it to a grainy photograph, showing it in its original splendour on a winter’s day. The house belonged to my paternal grandparents and then to my uncle. But my family sold it last year, not long after my uncle died, so now I observe this piece of my ancestry from the outside. Standing on the shoulder, I decide the photographed version is how I’ll remember Nan and Pop’s house and their outport fishing town. Across from the house, on the beach, my grandfather’s green-trimmed, yellow dory used to be ready to launch into Fortune Bay. He was the last fisherman in our family. Beach, bay, wharf, dories, fishing stages – all the similar structures are here, but the sounds and smells when fishing was in its prime are noticeably absent. As children, we used to watch the waves roll in and out from nearby this spot, atop the hill, overlooking all of town and the neighbouring community of Bay L’Argent.

July 1, 2018

Twillingate, Central

Mustard- and orange-coloured seaweed grips the shoreline and floats along the water, anchored to rounded gray stones, poking out from the shallow blue-lid. A small, white, fibreglass boat with an outboard motor is tied to the end of the wharf, on which sits a red ochre-coloured fishing stage. Behind it, around the bend of the rocky coastline, are four more – all white-trimmed, red ochre fishing stages. With one exception, they look newly painted or, at least, properly attended to and loved. Another small, white, fibreglass boat is seated on the grass for a rest. A rust-coloured spit of land divides the stage closest to me from those across the way, where, residential houses – mostly white, but there’s a red one, a light blue one, and a pale yellow one too – dot the land. The hillside backdrop rises above the water, then rolls away, concealing the bodies of several homes from view – only their rooftops are visible. Then the land rises again, culminating in bald-spots, where the wind has whipped the rocks clean of grass and shrubbery.

Mustard- and orange-coloured seaweed grips the shoreline and floats along the water, anchored to rounded gray stones, poking out from the shallow blue-lid. A small, white, fibreglass boat with an outboard motor is tied to the end of the wharf, on which sits a red ochre-coloured fishing stage. Behind it, around the bend of the rocky coastline, are four more – all white-trimmed, red ochre fishing stages. With one exception, they look newly painted or, at least, properly attended to and loved. Another small, white, fibreglass boat is seated on the grass for a rest. A rust-coloured spit of land divides the stage closest to me from those across the way, where, residential houses – mostly white, but there’s a red one, a light blue one, and a pale yellow one too – dot the land. The hillside backdrop rises above the water, then rolls away, concealing the bodies of several homes from view – only their rooftops are visible. Then the land rises again, culminating in bald-spots, where the wind has whipped the rocks clean of grass and shrubbery.

July 9, 2018

St Lunaire-Griquet, Northern Peninsula

The water is glassy, creating a dream-like, mirrored version of the world above. Its colour blue is a couple of shades deeper than the sky. I hold my paddle aboard the sea-kayak, restoring the stillness to the water. I have the feeling of being in a water-globe, held inside some transparent sphere in the middle of a landscape scene that, at any time, could be flipped upside-down, then right-side up to allow glitter-like snow to fall. It’s cold enough to be believable. In this globe, the landscape features an old merchant store, hinting at the past. It also holds an inflatable boat, revealing the present. Later today, this boat will zip tourists out to watch whales and icebergs, which still linger weeks into what people here consider summer. Later, I kayak out of the stillness into light, rolling waves; light enough to feel safe, but rolling enough to worry. Across the waterway, I spot the remains of the community of Fortune, abandoned in 1974 under the Fisheries Household Resettlement Program. Bouncing on the ocean, I see only a couple of structures standing. At the same time, fishers motor to the nearby fishing grounds, tending to their nets. Some 45 years later, the residents of Fortune are gone, but the fishers return for the codfish, which remain.

The water is glassy, creating a dream-like, mirrored version of the world above. Its colour blue is a couple of shades deeper than the sky. I hold my paddle aboard the sea-kayak, restoring the stillness to the water. I have the feeling of being in a water-globe, held inside some transparent sphere in the middle of a landscape scene that, at any time, could be flipped upside-down, then right-side up to allow glitter-like snow to fall. It’s cold enough to be believable. In this globe, the landscape features an old merchant store, hinting at the past. It also holds an inflatable boat, revealing the present. Later today, this boat will zip tourists out to watch whales and icebergs, which still linger weeks into what people here consider summer. Later, I kayak out of the stillness into light, rolling waves; light enough to feel safe, but rolling enough to worry. Across the waterway, I spot the remains of the community of Fortune, abandoned in 1974 under the Fisheries Household Resettlement Program. Bouncing on the ocean, I see only a couple of structures standing. At the same time, fishers motor to the nearby fishing grounds, tending to their nets. Some 45 years later, the residents of Fortune are gone, but the fishers return for the codfish, which remain.