Personal soundtrack- A chat with Jamie Fitzpatrick

November 2017

“When you’re young, you use music to invent yourself.”

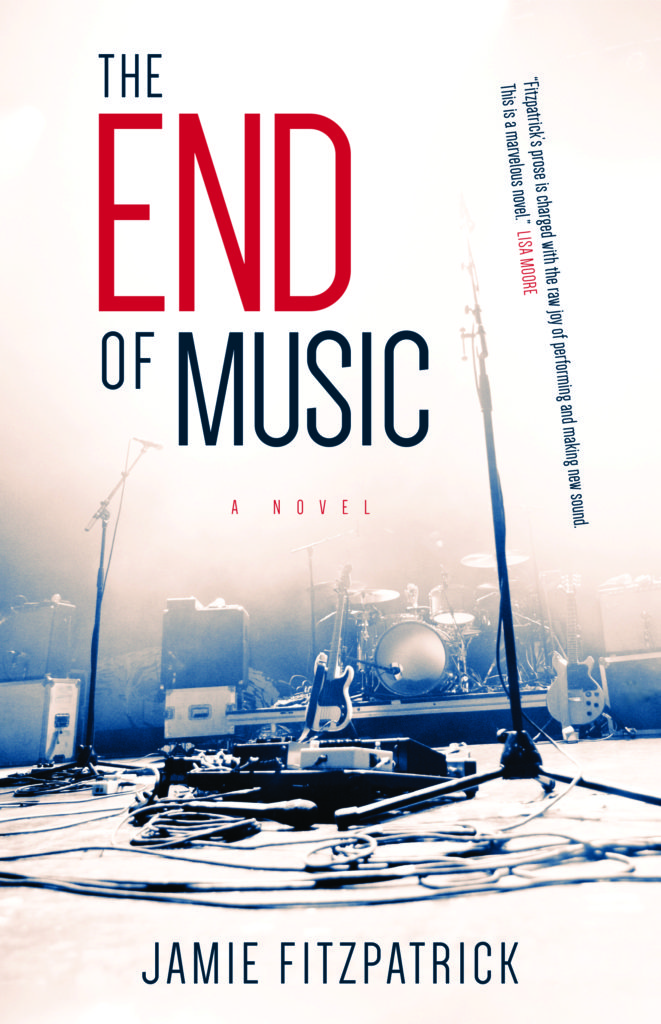

So said Jamie Fitzpatrick when I spoke with him about his second novel, The End of Music. Throughout the story, popular songs, from old standards to indie rock, shape the world of his characters.

Our conversation ranged from his hometown of Gander to whether or not it is wrong to make your children listen to The Eagles in the car.

R:

So, tell me about The End of Music.

The End of Music will be available later this month.

J:

There are two parallel stories in the book. One takes place in the 1950s and the other happens in the current day. The 1950s story is about a girl from out around the bay named Joyce who goes to Gander to work for one of the airlines and to forge a life for herself.

The present-day story is her son, who is already middle-aged. They’re both musicians – she mostly as a hobbyist, part-time after work, and he was in a band trying to strike it big for some years. She plays in a local dance band with a big-band sound, while he plays in a rock band.

R:

Why did you set one of the stories in Gander?

J:

In the 1950s and right up to the 1960s, Gander was this really young town. There were no old people there. There was almost no one who had been born and raised there. It was one of the big international service stations – the gas bar on the highway for trans-Atlantic flight.

When I was growing up, my parents and some of their friends would tell stories about that time.

R:

So tell me about your character Joyce. How does she get into the music scene when she arrives in Gander?

J:

She leaves home, hops on a train, and gets a job. The year is 1953. On her first night there, so goes to a dance at the Airport Club with her friends and there is a band playing. It’s a brass band playing what you would call the pre-rock and roll classics, people like Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra – when jazz was popular music.

She starts singing with them, but she isn’t an experienced singer. I mean, she used to sing in church growing up, that kind of thing, but she really comes around to it. Singing becomes a big part of her identity.

R:

Is the music of that time something that you recall hearing while you were growing up?

J:

A little bit. It wasn’t so much in our house as it was around the community. There was always a dance band in Gander, right from day one. If you talk to anyone from there who is a little bit older, like me, they would remember The Solidaires. That was the band for a long time.

They would have had signature songs, but I invented my own playlist based on songs that I really like.

R:

Like what?

J:

Oh gosh. Black Coffee is a great old song from that era. Baubles, Bangles and Beads is one of my favourite Sinatra songs. There’s a great old track, I can’t remember who did it, called Got a Feelin’ You’re Foolin’. I make reference to that. I also made some of them up.

R:

So what about Joyce’s son, Carter? How does his story fit?

J:

We start his story long after he has given up music. He went to Toronto and put a band together with a woman who eventually became his first wife. They played shows, built a following and recorded an album, but eventually it all fell apart.

He’s moved on to another life, and has remarried, has a kid, and is in grad school. Then his ex-wife calls him and lets him know she’s dying of cancer and that she wants to make some decisions about the archive of music they made together.

R:

Are the mother and son able to connect through music?

J:

No, Joyce and Carter don’t really connect through music, because by the time he was born, she had given it up. It was always a part-time thing. She loved it, but once she settled down, she just didn’t do it anymore, which would have happened with a lot of moms in those days.

Music is a bit of a gap between them. He knows that she used to sing, but they don’t really connect on that level.

R:

So where does Carter’s band fit into it all?

J:

In the contemporary story, the name of the band is Infinite Yes. It’s from a song title by Wintersleep, and I liked it because it’s a phrase that speaks to the boundless energy and heady ambition of youth. That energy and ambition has long since burned out when I tell the story.

I struggled for a long time to figure out they sounded like. If you wanted to nail them down to a genre, it would be along the lines of that kind of droning shoe-gazer type of thing.

R:

Like The Jesus and the Mary Chain?

J:

Yeah, more in that vein. I listened to a lot of different bands. It was a lot of fun.

R:

Was music something you always wanted to write about?

J:

I don’t know. It seemed like a natural thing to write about. I’ve worked with music most of my adult life, and I’ve devoured it since I was 12 or 13.

R:

So what bands are your biggest influences?

J:

In the mid-late 1970s I had this classic baby boomer moment when they did a television special and showed The Beatles appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, and that made me an instant fan. I’ve been one ever since. A very predictable answer.

Prince was the first one to knock me off the standard middle-class teenaged white boy rock n roll track. 1999 – that whole album kind of rewired my musical brain. Bjork had a similar effect at a later age.

Another really important band for me was Thomas Trio and the Red Albino. When we used to go see them they were just the best live band in the world. They were fantastic.

Sinatra has been a huge one for me, and that’s part of why that music plays a role in the book.

R:

You can remember hearing some of those artists for the first time. How has the new way that we listen to music affected the sorts of musical experiences available to young people today?

J:

Back when I was a kid, you could only experience the music that was available, and now lots of people would say there’s too much available. You can just go on Spotify and skip through a million tunes and if you don’t like it within the first 10 seconds then what odds about it?

I still think that’s no worse than hearing one good song, saving up to buy the LP and then finding out the other 10 songs are crap.

Also, even with the limited availability of music, which was basically what was at the department store in Gander, I still managed to fall in love with a lot of crap. In high school I had all The Eagles records …

R:

You have a young child. Have you introduced her to the bands that we’ve been discussing here?

J:

I don’t play too much old music that I grew up with for my kid. I think anyone who starts out with a small innocent child and indoctrinates in the stuff you listened to as a teenager – I think it’s criminal!

They shouldn’t have to tolerate classic rock in the car…

The End of Music by Jamie Fitzpatrick is published through Breakwater Books and will be released on November 28th, 2017.