Making Album Rock

November 2018

Did you know that there’s a place on the Northern Peninsula called Nameless Cove? Or that in the 1880s, a travelling painter made hundreds of brilliant watercolours of the French Shore, including some ingenious cartoons? Did you know that there’s a huge rock in Sacred Bay that takes its name from 1850s graffiti?

These are all things I learned as I worked on Album Rock: Looking back through the lens of Paul-Émile Miot, which has just been published by Boulder Publications. I like to describe Album Rock as part art history, part road trip, part detective story. Through creative nonfiction, poetry and photography, it delves into the mystery of a photograph titled Rocher peint par les marins français (Rock painted by French sailors).

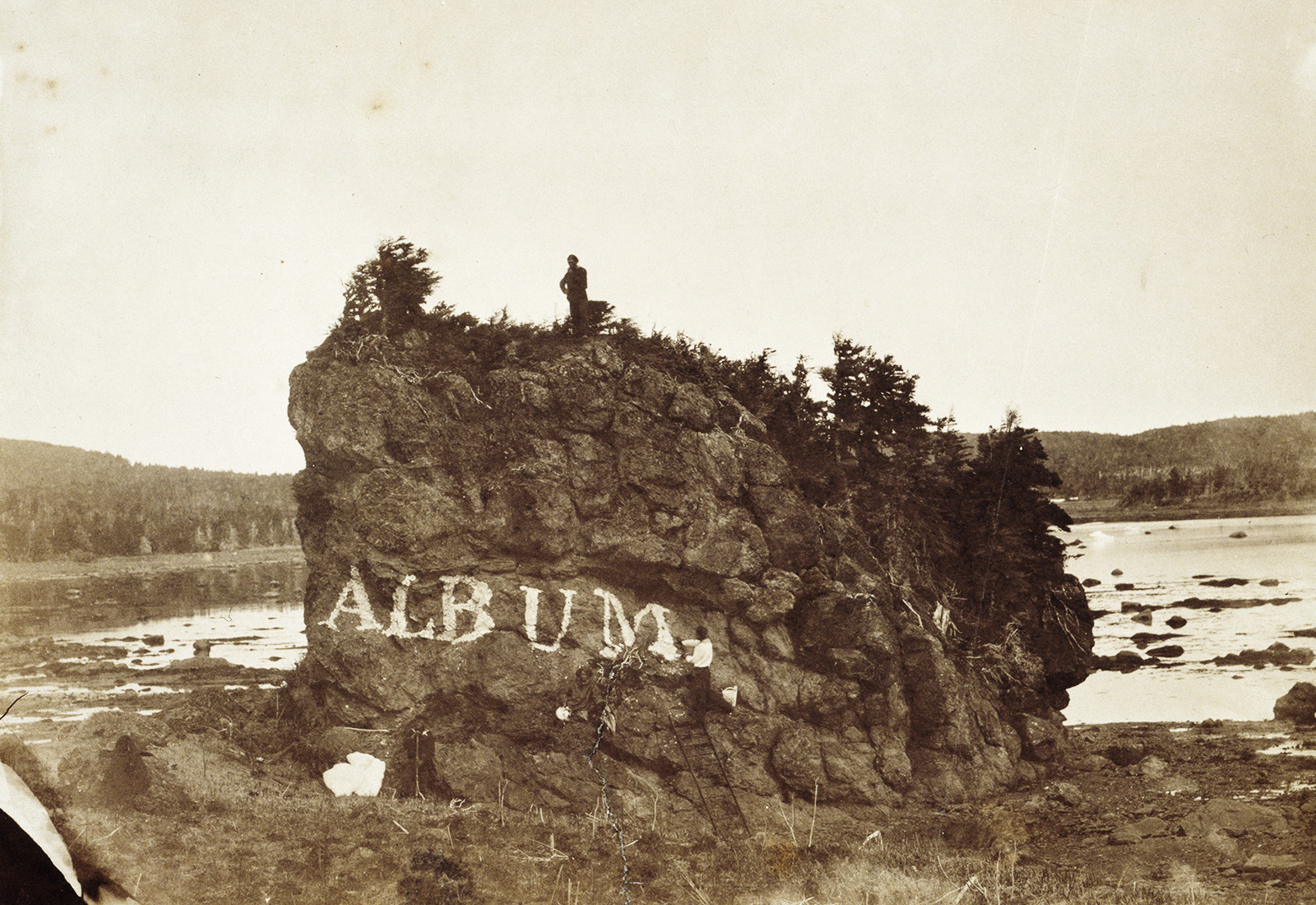

Paul-Émile Miot, Rocher peint par les marins français (Rock painted by French sailors).

I first stumbled across this image several years ago, on the website of the Corner Brook Museum & Archives. It shows a group of sailors posing on a large boulder on the Northern Peninsula. On the rock, they’ve painted the word Album in enormous capital letters. The photo was taken between 1857 and 1859 by Paul-Émile Miot, a French naval officer and amateur photographer who made some of the earliest photos of Newfoundland. Apparently, he’d intended to use it as the cover of a photo album.

The more I learned about Miot and his peculiar photo, the more it intrigued me. I love the startling precision of the painted letters against the rugged landscape, and the sheer whimsy of the scene. Historical images can be so stuffy and formal, but Miot’s photograph has a playfulness and charm that I find captivating.

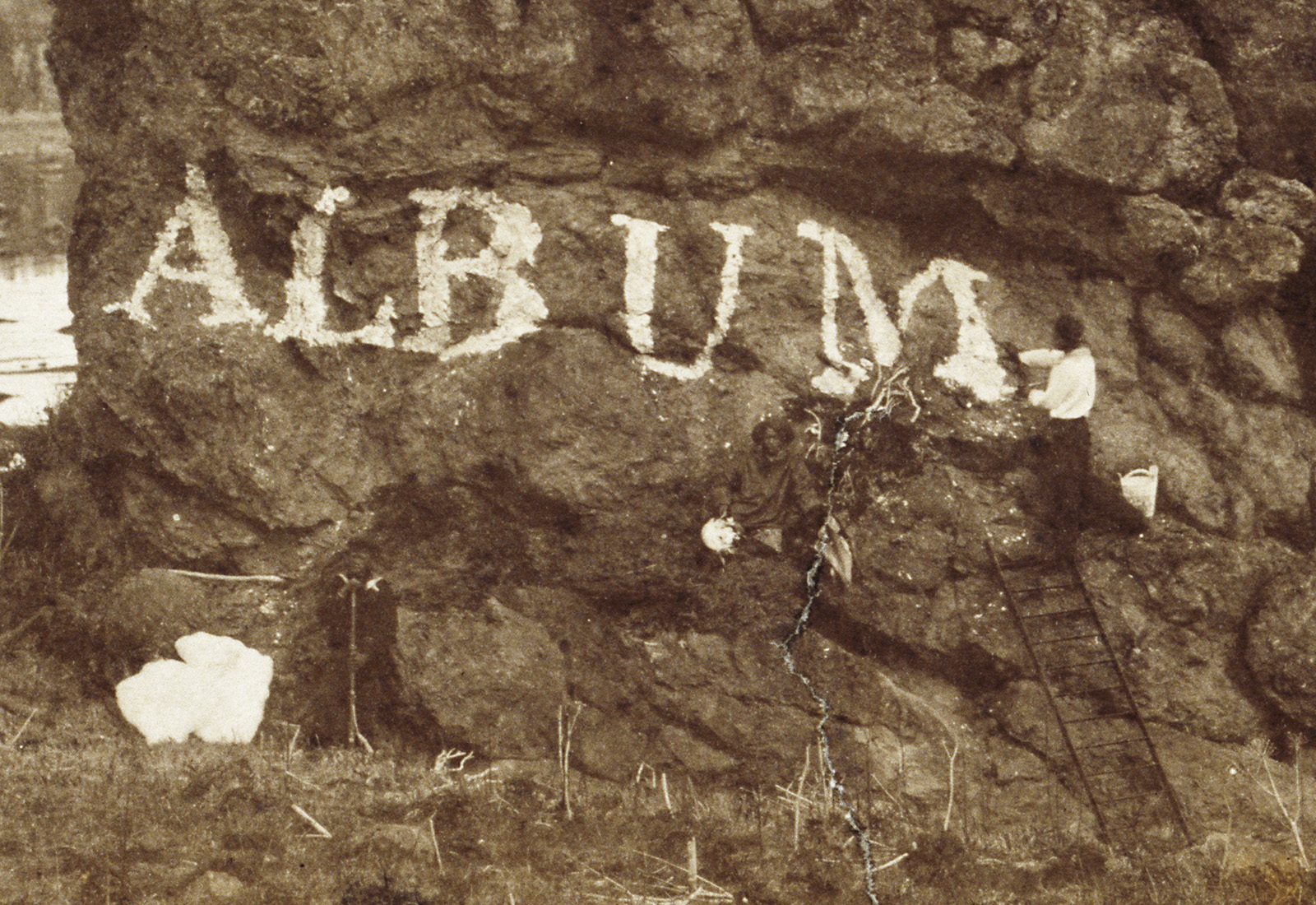

Detail of Rocher peint par les marins français.

I obtained a high-resolution scan of the photo from Library and Archives Canada, and things snowballed from there. I met with historian Michael Wilkshire, who was happy to share his knowledge of Miot and the French Shore. With the help of an ArtsNL grant and a friend with a car, I travelled to the Northern Peninsula to rephotograph the rock. I pored over nineteenth-century hydrographic charts at The Rooms, and later tracked down Miot’s original albumen print at an archive in Gatineau. A curator at the National Gallery in Ottawa showed me crumbling, leather-bound albums of Miot’s photos from voyages around the world: Peru, Uruguay, Madagascar, Tahiti.

Over 150 years after Miot took its portrait, the boulder in Sacred Bay is still known as Album Rock. Driving across the island to find it was a magical experience. We passed names spray-painted along the sides of the highway, and later the sign for Nameless Cove. I began to think about how a landscape becomes a place, and how names shape our perceptions of places.

Album Rock, photographed by Matthew Hollett in 2016.

Miot is best known for his photos of Tahiti and the Marquesas Islands, including many portraits of indigenous islanders. He also made some of the earliest photos of Mi’kmaq people in Newfoundland and Cape Breton. I met with Jerry Evans, a Mi’kmaq artist who has incorporated some of Miot’s photos into lithographs such as We Were Not the Savages, and began to consider Miot’s impact as an agent of colonial exploitation. Who was this person?

It’s hard to puzzle together the personality of a photographer who left very little writing behind, and sometimes my research felt like looking through a telescope the wrong way – everything was too distant, too small. Taking a cue from Michael Ondaatje’s The Collected Works of Billy the Kid, I used the poems in Album Rock to imagine outside the historical record, fictionalizing the scene from the point of view of the four sailors.

You can find such surprising and funny things while digging through archives. The Pilote de Terre-Neuve, published in 1869, is full of dollhouse-like illustrations of Newfoundland’s coastline, complete with tiny ships and houses. I also came across a sea captain’s letter to his daughter, in which he describes “seven little gulls recently hatched” that he is attempting to raise.

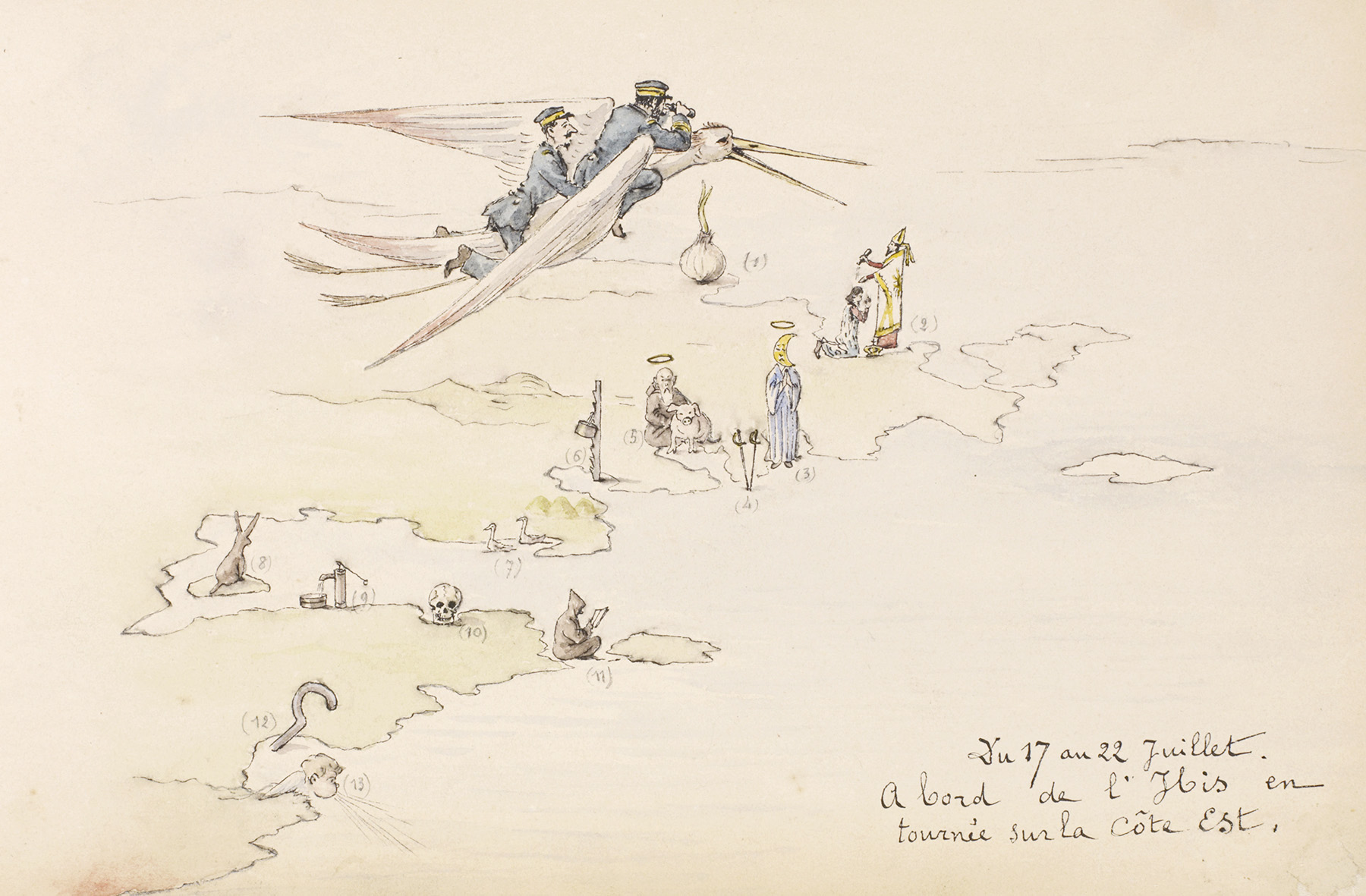

My favourite discovery was the illustrated journal of Louis Koenig, who spent the summers of 1885 and 1886 on the French Shore. His vivid watercolours show the landscape in lively detail, while his cartoons depict the misadventures of his shipmates with inventiveness and humour. In one, a comical swarm of mosquitos chases away a doryload of hapless sailors. Another shows an improvised clothesline, with clownish pants and shirts billowing from the rigging of a ship. And then there’s this amazing bird’s-eye tour of the Northern Peninsula, with place names depicted as hieroglyphs:

Louis Koenig, À bord de l’Ibis en tournée sur la côte Est (On board the Ibis touring the east coast)

These curious historical images – and the unexpected connections between them – gave me plenty to write about. But it wasn’t until I happened across a second remarkable photograph of Album Rock, taken decades after Miot’s, that I realized the project might turn into a book.

Thanks to the wonderful folks at Boulder, you can read the rest of the story in Album Rock: Looking back through the lens of Paul-Émile Miot. It’s in bookstores now, and is also available at boulderpublications.ca.