“I realized that I had a job of work to do as an artist” – Kate Story on ancient tales and modern angst

September 2023

Can you tell us a little about yourself?

I am a genderqueer writer and theatre artist. I grew up in St John’s in a house full of art, writing, reading, and talk, left home at 16, and ended up living and working in Nogojiwanong/Peterborough Ontario, as an uninvited guest on Treaty 20 Territory. My works – novels, short stories, performance pieces – almost always seem to have strong ties to home; most recently my debut collection of short stories came out, including several I wrote years ago, and I was surprised by how many of them were set in Newfoundland. My latest novel, Urchin, is set on the Southside Road, and was a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award (YA category) – I think there’s something potent going on there that I keep seeming to need to work out.

For a thousand-plus year-old manuscript, Beowulf still has a lot of cachet – and profile; even people who couldn’t tell you it’s an epic poem still have some awareness of the name. Why do you think that is?

A number of reasons – one being, simply, that it’s one of the few surviving written texts in Old English. It reflects Anglo-Saxon language and culture, and as such has been studied extensively by generations of scholars. It’s also a really compelling superhero story. Beowulf has “the strength of thirty men” and succeeds at feats like killing a monster, which has been eating the best Danish warriors for twelve years, with his bare hands; swimming to Finland; slaughtering sea demons; etc. The story also has an overriding atmosphere of longing and sadness, all mixed in with the ripping yarns. There have been some film adaptations – mixed success there, I’d say – and that keeps it in the popular consciousness too. JRR Tolkien’s The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings also draws on Beowulfian themes and language, another source if an oblique one.

I touch on this in the show: I love this poem, and at the same time have to ask what the world would be like if the weight of scholarship behind Beowulf went behind even one Indigenous language.

What’s your history with Beowulf?

Hahahaha, well, I’m a complete ignoramus. I didn’t study it in my brief career as a university student, but always thought I’d get around to reading it some day. I had this irrational notion, based on no evidence whatsoever, that I’d have some kind of intuitive affinity for Old English. When we were in lockdown, I thought, now’s my chance. I swiftly discovered that in fact I had no idea how to read Old English – our language has changed a lot since the 8th century – so I started diving into parallel translations, working slowly through those. I was really fascinated by the words that do leap out – it’s fun, like a kind of code – and slowly found myself being able to pick my way through the text. But my comprehension is very poor, honestly.

I also got really interested in something I wasn’t seeing given a lot of scholarly air time: the given circumstances of the people in the story (which, while written down in the 700s, refers back to oral folklore sources, and events and a few actual people from the 6th century). There were two volcanic eruptions in the mid-500s which led to climate crisis: a mini-ice-age, terrible famine, plague, you name it. Scandinavian elites began hoarding gold, and it’s thought that the legend of Ragnarök stems from this time. So climate crisis, and increasing migration and violence brought on by that, was another parallel for me.

How do you get from Beowulf to Anxiety?

I got the idea part-way through my exploration of various parallel translations that there could be some kind of performance piece in this. I was inspired and horrified by all the parallels I was seeing in present-day politics and the climate crisis. I also had an experience when Jagmeet Singh visited Peterborough – I happened to be walking by the regional NDP office before he arrived, and saw a friend of mine holding an NDP sign in a sea of yelling people waving Canadian flags. I joined him to make sure he was ok, and ended up standing there holding the other end of my friend’s sign for over two hours while people shouted and ranted (you know, all the F*ck Trudeau stuff, Covid is a conspiracy by the World Economic Forum, Jagmeet and Justin are gay, etc). I was kind of frightened, but, after a while, also bored, so I started talking to the yellers, and found three or four of them did want to connect. In some ways I found we agreed about what was wrong with our struggling community (Peterborough is a dumpster fire) but we totally disagreed on why. And I found that they had very few tools to determine what was a legitimate new story versus conspiracy rants; they’ve been systematically robbed of that capacity. And I found overwhelmingly that their rage was fuelled by intense anxiety. And then I had to admit that so is mine.

I invented a whole character who is a war reporter on the ground during the Bosnian crisis, because that war had a big impact on me when I was younger. I wrote a very long script about this person, who had a scholar father who has passed away, and then her dragon-lady mother inadvertently sets fire to the childhood home and all her father’s books, and of course she has PTSD from her war experiences … I researched the war in Bosnia, war correspondents (what an intense bunch!), and so on …

But I became aware that what I really had a hunger to do was to tell the story of Beowulf. The text itself is difficult – aside from the language, there are so many side-stories (probably these would have been touchstones for contemporary listeners and readers, but we really have to struggle with them). I also struggled to understand Viking age warrior codes of conduct.

I did more research on the phenomenon of violence, and came across the work of James Gilligan, a psychiatrist who, after years of work with violent offenders in the American prison population, came to the conclusion that nearly all violence stems from the experience of shame. This helped me make sense of some of the very weird things people in Beowulf do (go up solo against a dragon, for example).

And then I realized that I had a job of work to do as an artist. I needed to explore my own shame, and how that – and anxiety, and then rage, because as humans we find it almost impossible to sit with shame – get stirred up around all these current political storms, as well as my own past. I was seeing something really vital in the relationship Newfoundlanders and Labradorians have to language, a relationship to English that differs from the Upper Canadians I live among (and my mother was one of). I realized I was frightened of doing a show that touched on the work of my father, George Story, one of the authors of the Dictionary of Newfoundland English. I am very proud of my father’s work, and the whole Newfoundland Studies movement is so very important. I had a fairly uncomplicated sense of adoration for my dad. At the same time, growing up with that job of work at the centre of our family had an impact. I realized that even if it didn’t become something performable, I needed to stop hiding behind my war-correspondent-in-Bosnia character (and in any case, as someone who has never – yet – experienced war first-hand, it started feeling offensive to me to pretend to be someone with an intimate knowledge of that kind of violence). So then I dove in and started writing what has become the performance text Anxiety.

Can you share a little about your creative process with this project? Is it completely different from completing a short story or novel?

The advantage of a performance text is that you get to collaborate. The disadvantage of a performance text is that you have to collaborate.

When I write a novel or short story, I get to please myself, and only myself, especially in the first draft stages, and I love the freedom of that – but that also means I am constantly faced with myself, which frankly can get really tangly. I seem to need to swing between the two creation modes – they seem to feed different parts of my creator self. I generally know pretty early on in a creation phase whether the thing is going to be a performance or prose.

My first collaborator on Anxiety was Ryan Kerr, who is also my partner – he was forced to hear all my deliberations and mind-changing and rants. He and Joe Davies, a marvellous Peterborough writer, read over some drafts with me. Then Ryan and I got into the theatre (we run The Theatre on King, a wonderful little black-box space) and threw paper around and told stories and made charts, and I started playing different pieces of music that seemed in some way to connect to the work, and lay on the floor and cried.

I got a small amount of funding from the Ontario Arts Council’s recommender grants for theatre creators program, and from local arts council Electric City Culture Council, so I could rent the venue and hire some collaborators. I brought the fabulous choreographer and dance artist Marie-Joseé Chartier on board – she has such extensive experience with dramaturgy and direction, and she really helped us hone the characters, their voices and physicality. Marie-Joseé is also a francophone, and working with her helped me focus on what the hell is going on with the English language and Newfoundland identity in my piece. And I also brought in Patti Shaughnessy, theatre artist, director, and producer. Patti is fifth-generation Irish from the settlement of Peterborough and Anishinaabe from Curve Lake First Nation, so she has deep roots in Treaty 20 soil. I wondered how the themes of the rise of white supremacy and so on would sit with her; we talked about that, and also she made some key staging and text suggestions having to do with other aspects of the piece. I couldn’t have made this work without Ryan, Marie-Joseé and Patti.

I also brought in two composer/musicians: karol orzechowski (also known as doom-rap artist garbageface) and Benj Rowland to make some original music, and collaborated with Ryan and Paul Oldham and Brad Brackenridge on the set. We presented it as a work-in-progress to an invited audience, got feedback, and then produced it at The Theatre on King in November/December 2022 with the support of presenter Public Energy.

When the piece got accepted by the Festival of New Dance, we re-worked the set so we can ship it, and we re-mounted it at TTOK last week – just to try and get my feet back under me.

How does your theatre/performance activity fit in with your publishing resume (Blasted, Ferry Back the Gifts)?

I don’t know.

I think I made a grave error right out of the gates in terms of being both a theatre artist and a writer: my “brand” is confused. And not only that, I write across all kinds of genres – science fiction, young adult, fantasy, so-called literary fiction, historical, etc. It makes it a job of work to promote anything I do because there’s not a lot of consistency in terms of genre. But I’ve always been like that. Even my identity – I’ve settled on “genderqueer” because it comes closest to my lifelong experience of being in the world – is open to interpretation and changes. Am I a woman? Yes, but. Am I a Newfoundlander? Yes, but. Am I a writer? And so on.

But ultimately I have so much gratitude for having been allowed to make what I have. For my prose work, I’ve slid around working with a number of different publishers – partly due to the vagaries of the publishing industry, partly due to my inconsistency in terms of genre – and while that can be hard, it’s also enabled me to keep exploring multiple voices and forms. I have worked with many wonderful theatre and dance artists and companies over the years, and learned so much, while also finding places that nurtured my own work. I’ve been very lucky.

I hope people check out this year’s Festival of New Dance. It’s a wonderful festival, and I am honoured to be part of it. This year is so very eclectic; there really is something for everyone! And Anxiety kicks it off, and there two nights to choose from.

The Festival of New Dance runs September 26 – October 7 at Resource Centre for the Arts and other sites in St John’s..

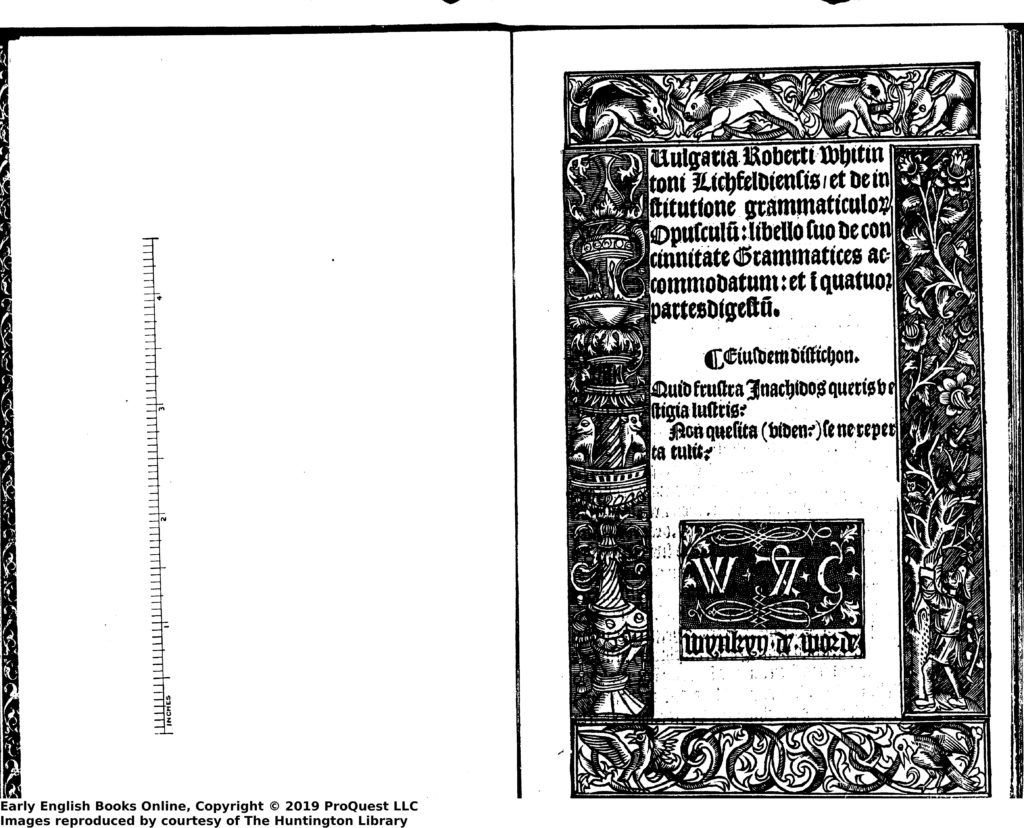

(Image: Beowulf and the Dragon.)