Working the Rock: Newfoundland and Labrador in the photographs of Edith S. Watson, 1890-1930

January 2018

In a world of 24-hour news cycles and digital ephemera, it seems impossible that there are stories that have not been told, images that have not been seen. And yet, in basements and attics, crawlspaces and even the cavities between walls, treasure troves of documents from the last century and beyond still gather dust, unviewed and unread.

Toronto-based writer Frances Rooney has found just such a treasure in the photographs and letters of Edith S Watson. A chance encounter with an image credited to Watson in a WWI-era magazine captivated Rooney, and started her on 30-odd years of research yielding multiple articles, a scholarly picture book, and now the Newfoundland and Labrador-focused Working the Rock, beautifully produced by Boulder Publications. “One look and I was hooked,” Rooney writes of the photograph that made such an impression. “Who was the photographer? Where was she from? What other photographs had she taken?”

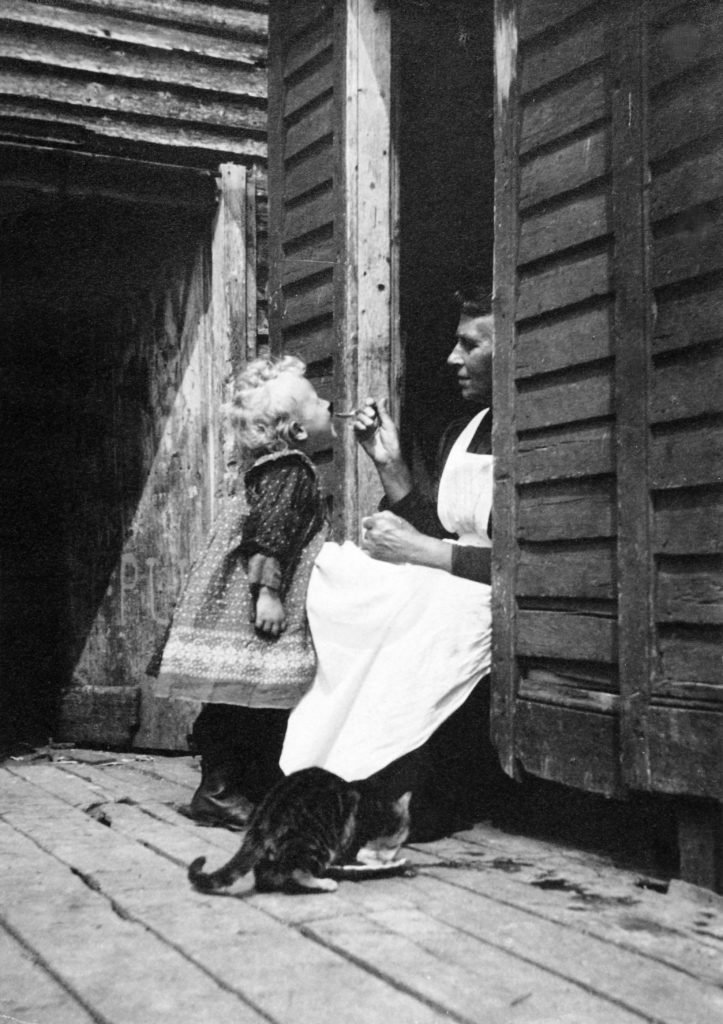

“Bread and Milk Time” black and white photo by Edith S. Watson, from “Working the Rock:Newfoundland and Labrador in Photographs of Edith S. Watson, 1890-1930” by Frances Rooney

The short answer is that Watson was an American artist, born in 1861 and raised on a tobacco farm in rural Connecticut. A well-educated, well-traveled woman, she made her living as a watercolour painter and then as a photographer. She was self-reliant and purposeful, selling her photographs to newspapers and magazines at a time when what we now call photojournalism was a burgeoning career path. By the turn of the 20th century, Watson was being referred to by the media as “Miss Edith Watson, the camera artist.” What first brought Watson to Newfoundland is unknown, but as early as 1891 or 1892, the photographer was travelling by coastal boat to outport communities like Bay of Islands, Fortune Harbour, Twillingate, Hermitage, and Burgeo with her cameras and darkroom equipment in tow. Watson’s visits to the Island, and occasionally on to Labrador, were frequent, and from 1913 on she was accompanied by her partner and creative collaborator, Bermudian journalist Victoria “Queenie” Hayward. The two journeyed together as a working couple, with Hayward providing articles to accompany Watson’s photographs.

And what is in these photographs? In Working the Rock, the images are primarily of women and girls, captured in their everyday clothes, often smiling warmly at their photographer. They are depicted performing the essential daily tasks of rural Newfoundland life: digging potatoes, tending to babies, carrying bundles of hay or firewood. There are a few photographs of men too, mending nets, helming ships, and in one memorable image, dismantling a whale, but Watson’s eye is clearly more drawn to female subjects. Social media era readers might not grasp the significance of these choices, accustomed as we are to images of women performing any mundane duty from compost-turning to bathtub-scrubbing. But at a time when most photographers were men, Rooney explains, “[h]onest depictions of ordinary women were almost invisible … [women] are often accessories to men or delicate creatures of decoration in a man’s world.”

“Delicate creatures of decoration” Watson’s women are not. These are hard-working matriarchs and daughters of fishing families. Their days revolve around the labour of the domestic sphere – cooking, washing, child-rearing, gardening, hauling water – and the seasonal demands of the inshore cod fishery. Many of the photographs Rooney has selected show women “making fish:” minding the drying cod so it doesn’t get scorched or damp, spreading it, stacking it. Other photos show women carrying water, two pails at a time, from community wells using an ingenious method involving a wooden hoop to keep the pails from spilling or hitting the water-carrier’s legs. This bit of vernacular technology was virtually unknown outside of Newfoundland, and is all but forgotten by contemporary Newfoundlanders, making Rooney’s book invaluable for its water-hoop photographs alone.

“Two Women, Four Buckets” black and white photo by Edith S. Watson, from “Working the Rock:Newfoundland and Labrador in Photographs of Edith S. Watson, 1890-1930” by Frances Rooney

Working the Rock is much more than a coffee-table volume of charming outport pictures. Rooney’s accompanying text is itself fascinating: the book is part Watson biography, part ethnography of the Newfoundland woman of a century past, part history of photography. In the book’s first chapter, Rooney writes, “I neither claim objectivity nor believe that it is possible.” Indeed, Rooney patches together the story of Edith Watson – both Watson’s own life story, and Rooney’s story of the “delicious months” spent surrounded by Watson’s papers – with the same affection that comes through in the faces of Watson’s subjects. She writes with the conversational ease of someone who knows her topic inside-out.

While Watson’s photographs exhibit the influence of Romantic art, Rooney does nothing to romanticize the lives of the outport women Watson encountered. She writes, “The dangers of the sea are well and vividly documented. The perils of being a woman living in outport Newfoundland have received almost no attention.” She goes on to enumerate the many challenges Newfoundland women faced during Watson’s time: overwork, malnutrition, frequent pregnancies and miscarriages, incidents of domestic violence, little to no maternal health care, and so on. Given these many tragic elements of rural life, it would be easy to characterize outport women as downtrodden wretches, but Rooney’s reading is nuanced and humane. She sees them the way Watson did: as “people who considered themselves ordinary but who shine … as independent, resourceful, and exceptional.”

If there is a flaw to be found in Working the Rock, it is that the publisher hasn’t anticipated how useful the book might be to researchers. While there is an excellent bibliography, there is no index. This is hardly a deal-breaker; it’s a slim-enough book that a bit of flipping back and forth won’t kill you, but a simpler method would be helpful for those using the book for academic purposes.

“Stacking a Fish Drum, Shoe Cove” black and white photo by Edith S. Watson, from “Working the Rock:Newfoundland and Labrador in Photographs of Edith S. Watson, 1890-1930” by Frances Rooney

Working the Rock will appeal to casual readers and to students of history, Newfoundland and Labrador studies, gender studies, and visual art. Readers familiar with the communities depicted (and there are many stunning images of various coves and harbours) will be eager to see how these places have changed in a hundred years. Older readers who can remember trips to the well with water hoops and hauling hay in homemade quilts will be interested in Watson’s perspective on these humble chores, and readers who love a good story will be compelled by Rooney’s narrative of how Working the Rock came to be.