Emily Urquhart: I like to say that I’m a journalist on the folklore beat

September 2022

Thanks so much for taking time to do this. First I should say I meant to skim through Ordinary Wonder Tales, getting the gist of it to prepare for this interview, but I am devouring it. I like your observation: “For every malady of the human psyche there is a folk tale.” Can you expand on this a little? When you discuss plagues, for example – the throughlines behind those tales seem to lead directly to today’s anti-science movements. It’s incredibly current, even urgent.

Our most personal fears, the worries that visit us in our waking night hours, are not new. We feel as if they are specific to us and our lives but once you regain some of your logic in the daylight hours, you can turn to the wisdom in the world’s great folklore bank and discover a story that might help you to understand your most confusing and difficult fears, or, if not understand these fears, at least let you know that you aren’t alone. I wrote the line you quoted in a story about seeing my deceased brother in the faces of living people. I was in my early 20s when he died and I was afraid that if I shared what was happening to me – these visions – it would be pathologized. It wasn’t until I began research for this story that I understood that these ‘sightings’ were a normal and well-documented part of grieving. More comforting, were the many folk tales and legends and beliefs across cultures that featured this experience.

My pandemic fears were also well documented in folk literature. The old plague legends are terrifying but so is scrolling the internet and the two storytelling forms hew closely to one another despite the centuries between them. Some legends touted ways to ward off the plague (ie burying children alive – yikes!). Some were stories of how people from elsewhere brought the plague to them. One legend was about how a king dispatched cholera to the poor people in the countryside in the hopes of getting rid of them. These all felt eerily familiar to me while living through our current pandemic: anti-science cures, xenophobia, marginalized communities being hit especially hard.

On the one hand it’s depressing to think everything we are experiencing is predictable, and, on the other hand it’s comforting. The good news is that the legends persisted! It means that people survived to tell these stories.

With regard to your writing style, I’m struck by the liminal places you construct in the text. The factual and the imagined co-exist, even co-mingle. You often underscore that belief and experience can be truth. Is that a tricky argument to make?

I like to say that I’m a journalist on the folklore beat. The two can seem at odds with each other, certainly. At its core, reliable journalism is about truth. But, whose truth? What is true? Early in my career I spent a lot of time working as a fact checker, and, later, as a magazine writer myself, being fact checked. I like the process and feel it’s necessary, but, there need to be spaces that can’t be fact-checked. My imagination, for example. Or, what I see in my head when I read. Beliefs in religion, or the supernatural, also, cannot be verified against some version of the truth.

A decade ago, I had a fact checking tussle about fairies that changed how I viewed ‘truth.’ I’d written that fairies acted with malevolence when switching a regular baby for a changeling, and the fact checker asked how I might prove a fairy’s intention. Barbara Rieti, author of Strange Terrain: The Fairy World in Newfoundland, was part of the discussion, and she felt that the fairies were simply acting in their nature. She said they weren’t trying to be cruel, it was just what they did! The fact checker was torn between our two opinions, but ultimately, we went with Barbara’s version because it didn’t cast the fairy behaviour in one light or another. What we couldn’t do was ask a fairy – the ultimate expert.

So, yes, it’s a tricky argument to suggest beliefs and experience are truth, but it’s also a way of approaching people’s personal stories with empathy and respect.

You also present the reader with a fusion of memoir, research, and lore. There are multiple perspectives or ‘takes’. How do you balance and incorporate these?

This book took shape in a similar way to a short story collection. In the past I’ve been assigned or pitched articles to newspapers and magazines and so I had a venue in mind while working on a piece and some direction from an editor. Then, I had the fortune of being Laurier University’s writer-in-residence one winter and I just wrote what I wanted to write, and how I wanted to write, and submitted pieces to literary publications after completing the work. I had great luck with this approach, and this buoyed my confidence in what I was doing. It changed the way I wrote. I felt free to explore beyond the confines of a specific genre. I wrote what appeared in my head and let curiosity guide my research, and there were no editorial voices or a specific audience in mind. The one tenet that I followed in regards to perspectives was that my research needed to be accurate, and tied to a reliable source cited in the bibliography.

Among other subjects, you delve into NL outport demographics, radioactivity, ghost stories, difficult pregnancies. Is there a unity or progression to the topics covered? Or is this, as Homer Simpson once defined History, “just a bunch of stuff that happened”?

I love Homer Simpson’s definition of history! That is absolutely true! I think it applies to this collection in that these are personal essays, and, so, by nature they feature a bunch of stuff that happened in my life, or, stories that interested me which led me to investigate them further.

The one theme that ties each story together is right there in the title. These are personal, true stories, but each one has a sense of wonder that propels them. This could be magical or supernatural, or it could be something more akin to the verb wonder, as in, something awe-inspiring, or worth considering. For example, in the essay Nuclear Folklore, I write that as a child, I heard the story of a mad scientist who left radioactive material in a home that my uncle subsequently lived in. I knew the house had to be destroyed because it was dangerously toxic but no other details. This was a part of our family folklore, but, then, when I reported on it – quite extensively – some plot points turned out to be true and others were stranger than the original story. In a second essay in the collection, the basis of a well-known fairy tale echoes a modern-day story of prenatal genetic testing. In a third I notice parallels between watching Law and Order SVU and the narratives of traditional ballads that I heard while working as the cover charge person for Folk Night at the Ship Pub. The stories tie together around wonder – which can be a question, a surprise, a pondering, or something beautiful, unexpected, and magical.

What’s next for you?

I am researching and writing about a giant hole in the ground – an open pit limestone quarry on the shore of Lake Ontario. I’m looking at the past, present, and future of this space: what flora, fauna, people, and buildings existed before they tore open the landscape, what it looks like today as they continue to mine for limestone, and how this space might look when it has been decommissioned. Whenever people dig, they unearth stories. I haven’t incorporated any folklore into this research, but I can feel that there will be a more spiritual, belief-driven angle to this tale. I can almost see it there, hovering on the perimeter of this enormous crater. I’m at the very beginning so I’m not sure where this story will take me.

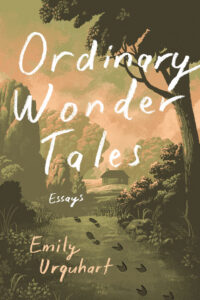

Ordinary Wonder Tales: Essays $22.95) is published by Biblioasis.

Author photo: Andrew Trant