Volatile Vulnerability in Pepa Chan’s Brush

BY Eva Crocker

April 2019

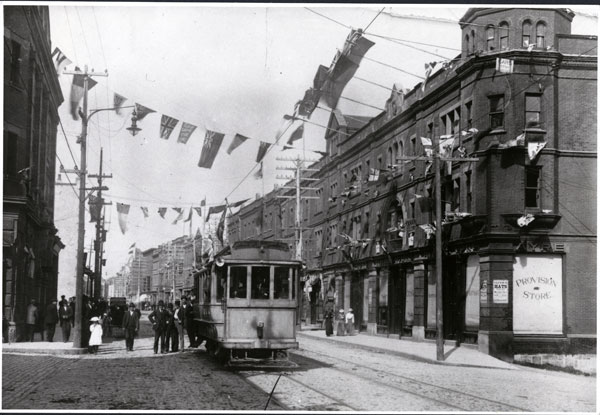

Pepa Chan’s Brush is installed in a secluded corner of The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery. The small gallery suits the exhibition, which uses the act of hair brushing to explore themes of intimacy, vulnerability, and the threat of violence.

When I went to see Brush, Chan welcomed me in and asked if I would like her to brush my hair. The walls of the tight space are painted a pale pink, evoking a childhood bedroom. There is a vanity with circular mirror mounted on it and a bench pulled up in front of it.

Pepa Chan

Brush

Installation detail

I sat on the bench and she spritzed my head with liquid from a slender spray bottle. On the table in front of me were a couple of sealed, see-through baggies with a few strands of long hair inside. Chan started gently tugging the brush through my hair, occasionally turning it over to pick hairs out of the bristles and lay them on the vanity.

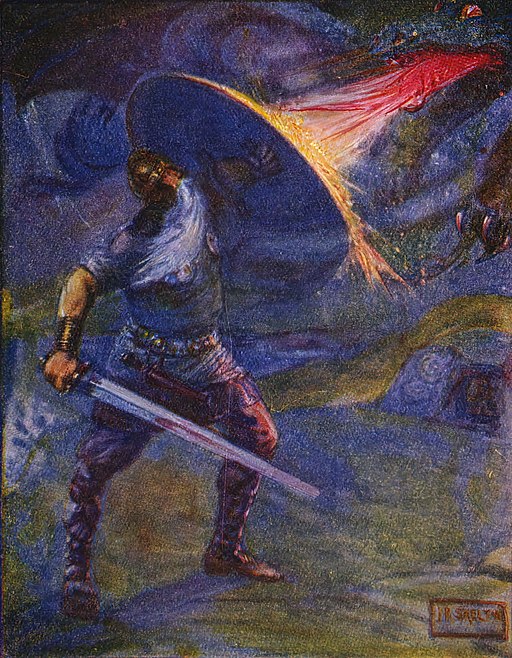

Where the glass of the mirror should be a video is playing: it shows someone sitting with their back to the camera, two disembodied hands methodically brushing the long brown hair. In the foreground of the mirror shot another disembodied hand holds a burning hairbrush. There is something disorienting about the distance between the burning brush and the thick hair – the flames should be melting the hair. At times the hands moving through the hair overlap with the burning brush, making the fire seem like a ghostly apparition.

Chan has a background in old-school special effects; in a past life she worked with latex and made monsters for movies. The fire in her video has the warmth and movement of real flames because the fire wasn’t added in digitally during editing. To create the deeply unsettling effect of the burning brush hovering near enough to singe the hair but leaving it untouched, she used an elaborate set-up that involved angling a mirror and a large pane of glass toward each other. She filmed a reflection of a reflection of the burning brush. The illusion created through the skilful deception of the double reflection, combined with the unusual experience of looking into a mirror and seeing something other than your own image, produces the feeling of having entered another realm.

Pepa Chan

Brush

Installation detail

Against another wall, ten hairbrushes with matchsticks for bristles are lined up on a narrow, curved-legged table. The first brush’s bristles are completely intact and the handle is a pristine white, while the bristles of the brush at the opposite end of the line have been reduced to a charred mess and the handle is stained with soot. The brushes in between are laid out in order of ascending decimation. It’s like looking at a series of stills from the burning brush video: time has been elasticized inside in the exhibition.

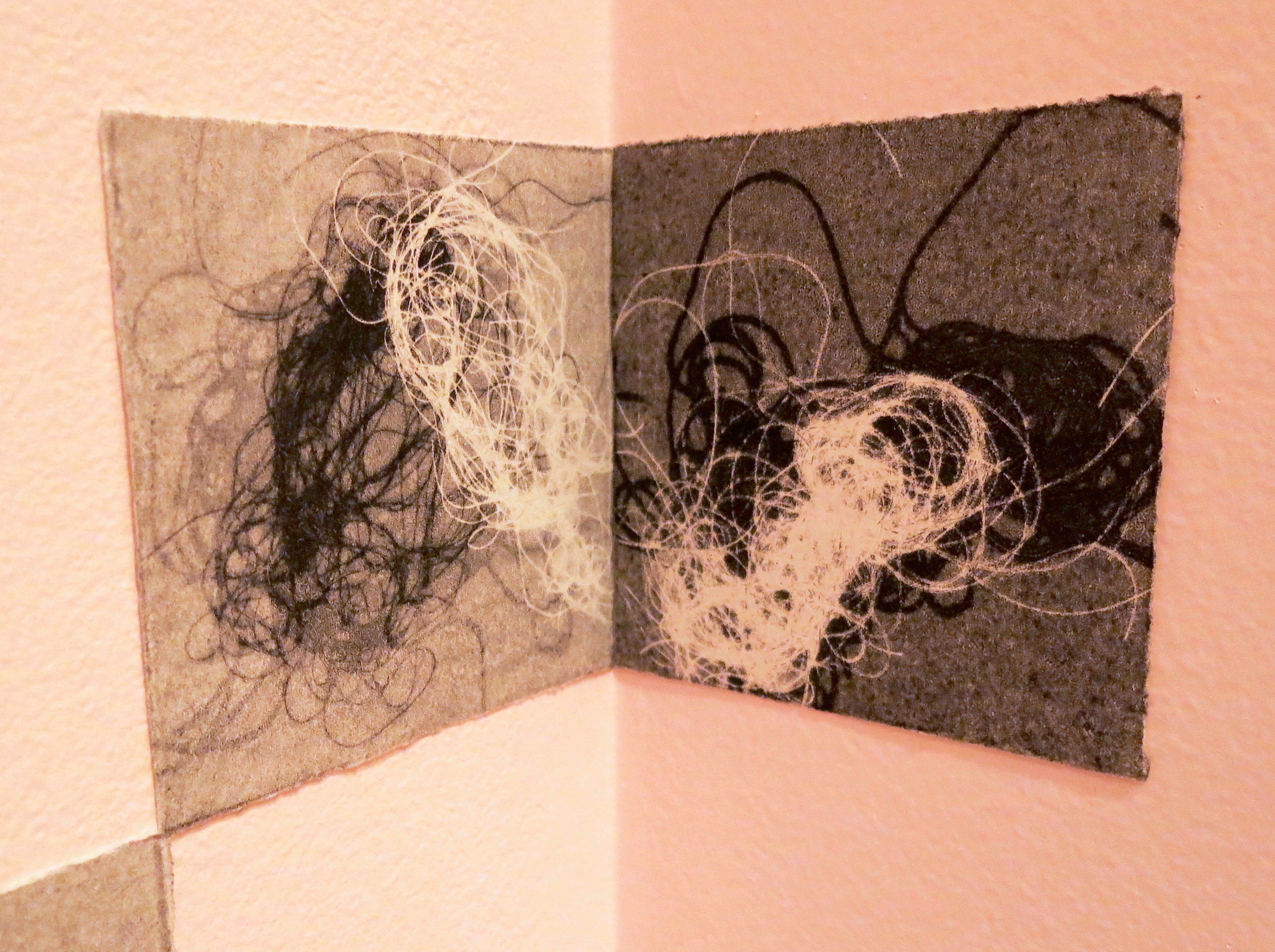

There are clusters of small, square, monotypes of squiggly snarls of hair in black and white arranged in geometric patterns on the pink walls, samples Chan has been collecting from hair brushing sessions with viewers over the course of the exhibition.

As she de-tangled my hair with her fingers, Chan and I talked about hair brushing as an act of care that parents often perform for their children. There is an intimacy in allowing anyone, and especially a stranger, to brush your hair because it recalls that parent/child dynamic. Chan is interested in how both physical and emotional intimacy make us vulnerable to being hurt. Brush evokes the privacy of a childhood bedroom and a fear of violence through the fire-y imagery. By brushing the viewer’s hair in this context, Chan forces the viewer to explore the awareness that being close to someone necessarily means giving them the opportunity to cause you harm.

Pepa Chan

Brush

Installation detail

We also talked about the unusual cultural significance of hair itself. How many religions require women to cover their hair in particular settings because it represents unruly, irresistible sensuality. How politicized the texture of racialized people’s hair is in our society. How we spend copious amounts of time and money on grooming our hair but we are viscerally disgusted to find a clump in the drain or a strand in our food. How hair contains our DNA and can be used by the state to confirm our identity and extrapolate details about what we’ve consumed, where we’ve been, and what we’ve done.

Chan recalled that one viewer said, “It feels like there are a lot of people in here,” as they took in the monotypes. Through these, Chan transforms the detached hair into art, re-imbuing it with the significance it typically loses when it falls out. Each acts as a souvenir of the intimate, vulnerable moment that particular viewer shared with Chan as she brushed their hair in the surreal world of Brush.

Brush continues at The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery until April 14th 2019.