Something of a Vigil: Saying Goodbye to Afterwords

February 2018

“We have tried to keep Afterwords going to serve our community and to support our family. In the end, we can do neither. Goodbye.”

I read the sign many times over. Actual grief swelled in my chest; my eyes felt heavy and ready to cry. I’d worked at Afterwords Bookstore for five years, but left when I went back to school. I knew the business was on shaky grounds. Every time I stopped by, I asked how Afterwords was doing. I asked like you’d ask about the terminally ill. How is Afterwords?

“Oh, we’re hanging on by our toenails,” David would say.

“Are there many bookless vagabonds these days?” I’d ask, echoing his words. Customers were bookless vagabonds. Parking attendants were Meter Maids of Doom. I liked slipping into the old lingo. I’d never really wanted to leave.

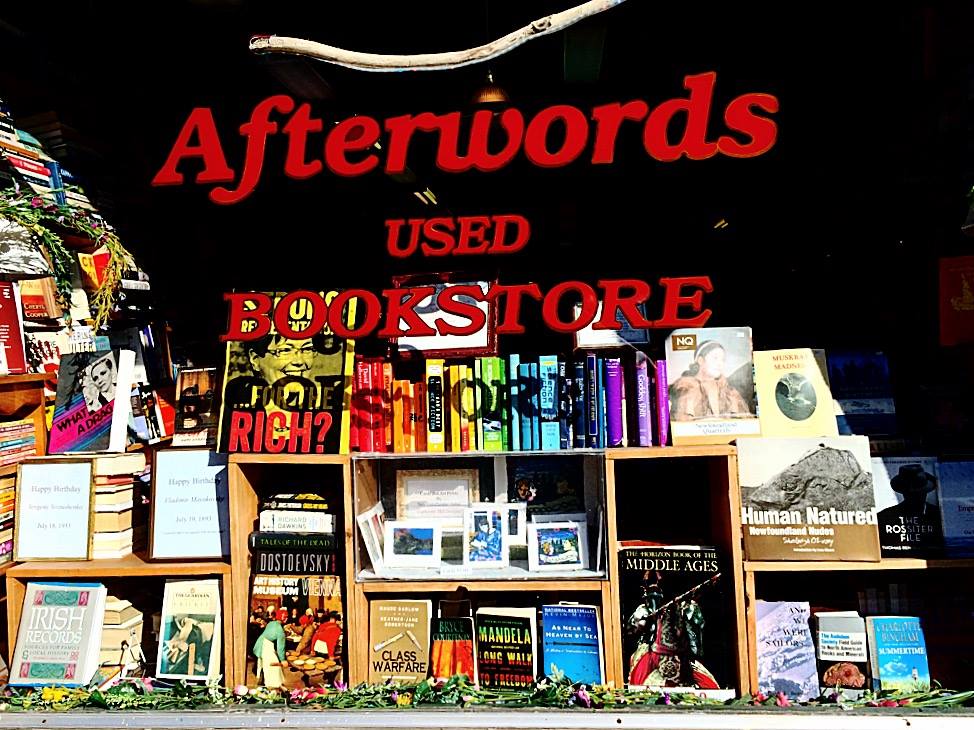

Photo from Afterwords facebook page.

David would shake his head sadly. Then he’d start muttering about online shopping, or the demise of education; he’d say that politicians want a compliant, uneducated populace, that this was only the start of it. Then he was talking about flooding in Bangladesh, bombing in the Middle East, various shades of local incompetence. We’re ravaging Africa for cellphone minerals, he’d say, but nobody thinks about this. Our lives depend on the suffering of others, and we’re all too self-absorbed to see it.

I agreed with most of it, felt grateful for the reminders, but still wracked my brain for a gentle diversion. It was all tied together, the slowing of business and the looming world order. And yet, Afterwords did hang on. In spite of so many things. I knew it was precarious and I worried about it, but the notion of its closure was too terrible to face. I’d never really and truly imagined its absence. It still hasn’t sunk in.

At the moment, there’s a drama at play: The end of an era. The collective mourning. The final sell-off (at last, the bookless vagabonds are out by the dozens). But when I think about the next part, the part where Afterwords just doesn’t exist, I am back to an in-the-body sensation of grief. It’s not a shrug, not a sigh. It feels like the city’s being hollowed out, scraped clean of its heart and guts and soul – its brains. The downtown is getting a lobotomy. What will we do without Afterwords?

—

When I’d mention working at the bookstore, I was usually met with the same response.

“Afterwords? Next to the Tim Horton’s down on Duckworth Street? Do you work with the Man Who Smokes the Pipe?”

Those words were certainly capitalized. His pipe was the perfect prop. In allegiance to it he’d step outside, leaving the store to become a fixture of the road. Pipe smoke is its own perfume, as most people know. The pipe was paired with a thrift store suit. He wore a hand-sewn flower in his lapel. As a sight to behold, he was enigmatic. People often asked what he was really like.

David used to be a sailor and had sailed around the world, carrying bags of paperbacks all the while. In summer, he kept the front door of the store open with a series of sailor’s knots. He showed me how to tie them, too. He was also a published poet and, as he often remarked, he strived to “wield his pen as a sword.” He felt that poetry – indeed, all art – should address injustice. I fell in line with this idea for awhile. I read the dystopian novels I was recommended – 1984, Brave New World, and We (the Russian predecessor and inspiration for the others). But I didn’t share David’s disdain for coming of age novels. What about art for art’s sake? What about empathy? I took a philosophy course, and learned about the sublime.

I started to voice counter-thoughts, but realized it wasn’t much use. David’s opinions were part of the experience. There was usually something to admire about them. I tended to listen, veering somewhere between a sponge and a sceptic and back again.

A businessman, he was not. Certain books incensed him, especially books with historical inaccuracies. One time, I watched him discourage someone from buying The Colony of Unrequited Dreams in his own store. The author had gotten the geography of old St John’s all wrong, amongst other things, which infuriated David.

“When James Joyce wrote Ulysses,” he would say, “he wrote letters asking about the number of steps on a particular stoop.” David clearly revered this kind of care and attention. He couldn’t contain his contempt for careless mistakes, and was driven to express it, even when doing so hindered his own self-interest.

Some customers said we should up the prices. Many rare finds and sought–after books were sold for 90 cents. Shouldn’t we try and reach for a profit? But we had a pricing system, and we followed it. Most of the time, the cost was based on the sale price or year of publication. The market didn’t change anything, because accessibility was the most important part of the whole operation.

I loved the customers. It was a congregating grounds for idle wanderers, political discontents, the homeless, the lonely, writers, children – really, just about anyone. It was a place of longing, of so many kinds – escapism, curiosity, self-knowledge, fantasy – the furthering of any impulse or trajectory. We kept lists of the books people were looking for, and called customers up when the books came in. There were the vague hopes for books unknown – Anything on vaudeville; Books about robots from the 80’s. There were the nearly completed collections – the people who’d already bought seventy Agatha Christies or Danielle Steeles from Afterwords, and were patiently waiting for the rest of the batch. I knew who liked the books I liked; knew the yearning for local fairy lore; knew that the list of Kurt Vonnegut hopefuls was perpetually three pages deep. I loved sifting through our newest used books. Sorting them in categories, scanning the wish lists, setting things aside for my own perusal. Stumbling on the marginalia, the letters, the grocery lists, the long-lost bookmarks from Montreal. Reading the twelve-page story, handwritten by a child, that came in with the books that time. Dusting off the spines, blotting out the pen strokes, choosing the shelves for the books to live on.

The cat books were placed beside the True Crime section. This was a strategic decision. David wanted True Crime fans to have cats, so that they would learn to know terror and, in doing so, rid themselves of their cravings for murder. He hoped that with a cat purring at their side, reformed True Crime fans would turn their attention to mysteries. I loved the warped logic of this, and made the cat book section a top priority.

As David often said, “The book you need is right next to the book you’re looking for, which isn’t here today, but we’ll get it for you when it comes in.”

There was a bedraggled palm tree in the corner named George. A Morse code poem was broadcast in the window, cycling through in an endless loop. A couple years ago, in response to the e-book craze, David set up a window display with various items: a reel to reel tape from the 50’s, an 8-track from the 1970’s, several types of floppy disks, and a 100-year-old book, set alongside a framed caption: “Access the Information.” All but the book had become obsolete.

—

I first saw the closing sign online. Later that day, my roommate and I walked down towards the window. We fixed our eyes on the sign in disbelief, and stood reading it over for a while. Other people in the road joined us, as we tried to find words for the tragedy of it all. It felt like something of a vigil.

The busker on the corner said, “It’s horrible, isn’t it? I always changed up my cash in there. They never mentioned anything to me, nothing.” He knows me from the store. He seemed dismayed about being kept in the dark.

I relayed this to Catherine, David’s wife, a couple days later. She said that sometimes, the busker made more in a day than Afterwords. People were saying all kinds of things. A Tim Horton’s employee, shocked at the news, said to Catherine and David, “You can’t close up. You two are the furniture down here.”

You can tell that nobody wants this to happen. Crowds are swarming the store like never before, drawn by the sales, or maybe just the need for one last look. There was something disheartening about it, I said to Catherine. She said, “I know, but you can’t think of it that way. You have to feel glad that people are finding things to read.”

Afterwords closed in October 2017. In January 2018, Broken Books announced it was moving into the space.