Pleasure and Other Nutritious Matters

May 2018

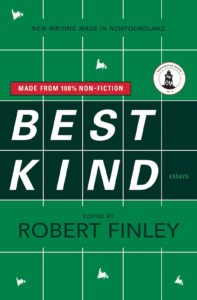

This is an excerpt of Elena Slawinska’s story Pleasure and Other Nutritious Matters. The story is part of a new collection released by Breakwater Books called Best Kind. The collection features outstanding non-fiction written as part of the creative writing program of Memorial University’s Department of English. Best Kind will be launched later this month.

This is an excerpt of Elena Slawinska’s story Pleasure and Other Nutritious Matters. The story is part of a new collection released by Breakwater Books called Best Kind. The collection features outstanding non-fiction written as part of the creative writing program of Memorial University’s Department of English. Best Kind will be launched later this month.

Wednesday, October 14th, 2015.

One o’clock.

Temperature +23 C.

Atmospheric pressure 1,018 mbar.

Wind SW 21 km/h Libeccio.

The Mediterranean Sea is calm and turquoise.

The beach is downwind and far enough not to carry the voices of the vacationers, in this season mostly Germans.

Not an unusual autumn day in Liguria.

The south-westerly wind from Libya seems to blow Gianni to our table as soon as we sit down. With his usual warmth, he hugs and kisses both Michael and me, updates us on his new granddaughter. Seeing that we are hungry, he gets to the point.

‘I have fresh acciughe today, caught last night just around the point. Marinated or breaded and fried. I’d go raw, if I were you: they’re almost alive.’

Nothing compares to marinated fresh anchovies: the intensity of olive oil, and the acidity of lemon and vinegar wed the tenderness of the raw fish in a grand feast. Gianni uses a touch of hot pepper, which brings the fish to swim in your mouth. Then, what it does to you, just as Gustave Flaubert describes in his mirage of lemon ice during a trip across the desert,

it bathes the uvula, glides over the tonsils, descends into the gullet, which is only too happy, and it falls into the stomach which bursts with laughing, so delighted it is.

‘Marinated!’ we blurt out in unison.

One of his waiters has just brought a carafe of sparkling white wine.

‘This one is on the house,’ Gianni decrees.

Italy provides the ultimate food-based therapy to help us reconcile with life. We indulge in two long epicurean meals a day, often with friends or family. Social life revolves around mealtimes. You are always allowed and even encouraged to stretch your meals for hours. Yet, there is no flexibility for the starting time: fixed and confined to a one-hour slot. It does not surprise me to find an Internet entry for the proper time for lunch: ora di pranzo, which translates not as time but hour of lunch: 12:30 PM, slightly earlier in the north and later in the south but always punctual. No chance to find a restaurant open at 4 PM in Italy, even on Sunday.

There is a major distinction between the dictionary entries in Italian and English for pranzo and lunch. They have in common the meaning of representing a meal taken in the middle of the day, but, while in English lunch is often defined as a light meal, in Italian pranzo is the main meal of the day. Other meanings highlight its conviviality, richness and abundance, such as in pranzo di nozze (you would always say pranzo even if the wedding celebration happens at night). One of the most interesting connotations of pranzo is that of space. Italian houses have a sala da pranzo, not a dining room, which is congruous with the importance of this meal in the culture.

Luckily, living in the United States and then in Canada has inoculated me against the bondage of meals at specific, fixed times and places. My new habit is declassed by my father as feeding, nutrirsi, as opposed to eating, mangiare. You should read the word feeding with a tone of contempt. Solitary ingestion of calories is a deadly sin to any Italian, as every day, twice a day, you are to infuse your food consumption with social rituals pivoting on conviviality. The ceremony includes admiration of the food, comparing it to previous similar recipes, assessing of someone’s mother’s inevitable superiority in the rendering of the recipe. A long, winding chat to accompany the many-course meal, all courses to be consumed separately, in a specific and immutable order, each on a clean new plate, every day, twice. Unthinkable on the other side of the Atlantic, where breakfast often slides into the middle of the day, and supper is so early to encroach on lunch. The one-course dish never contains a single food type but an odd assortment of colourful and, mostly incompatible, “things.” I am sure you can hear the voice of my father here.

After the piscatorial introduction to our pranzo, Gianni is back for the main courses, primo and secondo.

‘As a first course, try spaghetti con porcini,’ he offers. ‘I found them this morning in the woods up there, firm and big, twenty-five of them! All that rain in September, and then this heat…’

I look at Michael and we both nod at Gianni, mouths already watering with anticipation. Gianni always delivers…