“One of our core beliefs is that all records should be seen as living things”

February 2023

You compact so much information into the book, introducing readers to pioneering filmmakers from Nancy Columbia to Miriam Look MacMillan, and influential projects from Last Days of Okak to Last Stop Garage. And yet it’s not text-heavy. What was the process of finessing that?

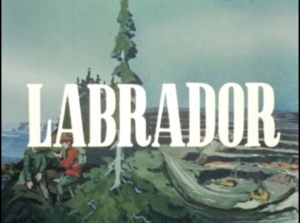

Mark David Turner: This might boil down to having a great deal time to think about how we were telling this story and, also, by integrating design into the creation process very early. Writing about film that aims to be comprehensive — whether it’s from a specific culture, a region, or a time — tends to drift from the thing itself. Using images to anchor the story allowed us to stop that drift and show a story rather than just tell one. This, I think, is most obvious in places where we have an image from a film and an image related to the same film. Atlantic Films’ Labrador (1963) is a good example. The frame enlargements we include from the title sequence give you a sense of the resources invested in making the film. But with the photograph of the St John’s premiere of the film in the next spread, you can see the power dynamics at work.

Morgen Mills: Haha, Mark mentioned “a great deal of time.” In a very real sense, it took us 12 years to make this book. We did so much talking in all that time, and we’ve both learned that when it comes to commentary, less is more. Of course we need to situate the images in context so that people know what they’re looking at, but throughout the project we tried to choose images that speak for themselves better than we could ever do.

You explain the roots and advancements of documentary cinema, which comprises so much of Labrador cinema. Why do you think there isn’t there a tradition of narrative cinema? Do you see one developing?

MDT: Historically, most film made in Labrador was by people from outside Labrador. Those filmmakers often came to Labrador precisely because of the value of its documentation. It’s a similar story across the North. When film equipment became readily accessible in the region via Memorial University’s Extension Service in the 1970s, Labrador was fully engaged in regional organization and documentary became a valuable tool in that organization as it allowed people to talk about their circumstances directly. The longest running television show in Labrador, OKâlaKatiget Society’s Labradorimiut (1983-2011), remained popular in part because it was the only audio-visual document of contemporary life in Northern Labrador. As narrative cinema tends to require the presence of an industry (crew, producers, infrastructure), the absence of industry in Labrador limits opportunities to create narrative cinema. I’m not certain that the population exists to sustain an industry in the way that has taken shape in Newfoundland, but I think it is likely that we will see more Labrador presence in the provincial industry in the short to medium term.

MM: I’m in the middle of writing my PhD dissertation on prose story-telling in Labrador, so this question puts you in real danger of getting a far longer answer than you could ever have wanted! In a nutshell, though, I think every culture tells its stories in its own ways. There are no stories that Labrador filmmakers can’t tell, there’s only what they choose to tell and how they choose to tell it. Filmmakers sometimes like to tell narratives that viewers can relate to, but other times, they prefer to show a world in which viewers can see themselves and others — and so far, I think that’s mainly how people have chosen to do things in Labrador, most of the time.

Where do you think Labrador Cinema goes next? What about you, what are your new projects?

MDT: We would like to see the book as a focal point for more activity concerning filmmaking in Labrador. At both of our Happy Valley-Goose Bay and St John’s launches, we used the opportunities to screen more historical films with the idea that they would help to bring the book to life. But what we are discovering is something of an opposite effect. The book allows us to have richer conversations about the films — what they document, why they document it and what it means to watch it now — because it creates a context. We are planning more screening-discussion events this year. We also would like the book to serve as a tool to help develop filmmaking in the region and we’re happy to talk with anyone about how we can best advocate for this.

Beyond this project, we are excited to continue to develop our imprint, Brack and Brine. Publishing is part of what we do — and we have another project or two in the works — but our imprint aims to help Labradorians, Newfoundlanders, and people in the Northwest Atlantic generally do creative things with their records.

MM: Labrador Cinema is just one expression of a long-term relationship that Mark and I now have with these films and the whole medium of filmmaking in Labrador. It’s been a tremendous pleasure to share that relationship in book form, and also with the screening series and all the different talks and media interviews, plus at the Big Land Film Festival last year. We have some plans for web-based initiatives and more ideas that we can’t announce quite yet. Let’s just say that we’re not going anywhere!

One of our core beliefs is that all records — whether they’re texts, photos, videos, or whatever they are — all records should be seen as living things, as points of connection or possible connection between people. As a business, we work with records, but really we only do so in order to work with people. Real communication isn’t about publishing things and sticking them on shelves, it’s about keeping conversations going. We love what we do, and we’re looking forward to whatever comes next.

Images: frame enlargements, Labrador (Atlantic Films, 1963), The Rooms Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador

Labrador Cinema is available from Brack and Brine (180 pages, $40.00)