Matthew Hollett: “There’s a kinship between photography and poetry – they both tend to be smaller, quieter ways of making things”

April 2023

Can you tell us a little about yourself?

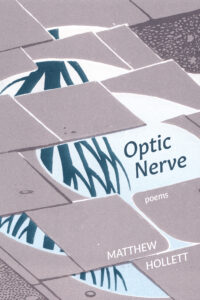

I’m a writer and photographer in St John’s. My background is in visual arts, and my writing is often very visual – I’ve published essays of writing and photos, and I enjoy writing in response to images. My poetry book Optic Nerve has just been published by Brick Books – an earlier version of it also won the NLCU Fresh Fish Award a few years back. It’s a collection of poems about photography and visual perception, with poems about peering inside an eyeball, looking closely at moss or frost, and foraging for filmstrips in the ruins of a burned-down cinema.

I’m currently writer-in-residence at the Al Purdy A-frame in Ameliasburgh, Ontario – it’s a charmingly rustic house by a little lake, jam-packed with books and birdsong. Poet Al Purdy and his wife Eurithe built the house in the 1950s. I’ll be here for six weeks, working on a new collection of poems about walking. I found out about this residency through my friend Anna Swanson, who spent time here a few years ago. I’ve only been here for a few days so far, but it’s been rejuvenating to get to know a new part of the country. These endless flat farm roads are a totally new landscape for me.

Good writing is visual, but your work seems to reinforce it as a foundational starting point (beginning with your title). Does your writing start with looking? How does it complement or alternate with your own visual arts practices – how do you decide if something is a photograph or a poem?

There’s a kinship between photography and poetry that I love – they both tend to be smaller, quieter ways of making things, as opposed to brawnier works like novels or oil paintings. I walk everywhere, and often take notes in the form of photos or jotting down details. I enjoy the process of placing two things together so that they resonate with each other, creating a larger meaning. You can do that within a photo or a poem, or you can build a sequence of images or a series of poems. Or you can place photos and writing together, weaving between language and image. So they’re very complementary processes for me.

Yes, I think my writing begins with looking. Here at the A-frame, there’s a beautiful writing shed that Al Purdy built to work in. It has a big desk, a typewriter, walls of books – and no windows! Al liked working in darkness. I haven’t spent much time in there, as I much prefer his kitchen table with its expansive view of Roblin Lake.

Your poetry includes what some might find surprising “unpoetic” work choices, like “persnickety” and “noggin,” let alone allusions to Looney Tunes cartoons. I guess this isn’t a question, but I kept finding these delightful moments in the text.

Thanks! That’s something that I love about poetry, how it can become a playground for language. Optic Nerve is full of puns and wordplay, particularly in some of the shorter poems (“A squiggle ripples, a scurry / wriggles, a waggle squirrels / along a wire”). I write poems with reading aloud in mind, so sound is important. There are poems in the book that are like songs, lectures, stand-up routines, and sermons.

There’s a lightness to wordplay, but it can be employed for more serious purposes as well. One of the poems in the book, “Portable Keyhole”, examines the male gaze in Hitchcock’s Rear Window through a sort of relentless stream of synonyms for a voyeur’s camera: a body snatcher, a supervillain monocle, a grin reaper, a photon torpedo.

You reference visual arts figures like Milne, Vuillard – and particularly André Kertész; you set three piece “after” him – where did you come across him? Why are you so struck by him?

André Kertész has been one of my favourite photographers forever – he’s one of those artists I latched onto in art school and always return to. Just the other day, I was flipping through a photo history book and whenever a photo caught my eye and made me stop turning the pages, it was by him. Kertész was a Hungarian-American photographer known for his slightly surreal street scenes. His photos often capture some unexpected juxtaposition of things – a train, a bird, someone silhouetted in the distance – that feels surreal at first glance, but seems to grow more meaningful the longer you look at it. He has a marvelous eye for composition, and for suggesting a story in a single image. I often think of his work when I’m wandering around with my camera, and [as noted] three poems in Optic Nerve are inspired by his photos.

Can you discuss your interest in natural philosophy and scientific theories such as Olbers’ Paradox?

I’m a pretty eclectic reader, and find most of my books in thrift stores. There’s one particular series of books called Very Short Introductions, published by Oxford. They’re tiny things, each only about a hundred pages, that are meant as introductions to different topics. They’ve published about 750 of them over the years, on everything from Spinoza to Synaesthesia to the Spanish Civil War. Whenever I see one of those in a thrift store, I always bring it home. They all have these Rothko-inspired covers that are very colourful together on a shelf, and I have about 50 of them. So that Olbers’ Paradox poem came directly from me reading A Very Short Introduction to the History of Astronomy. There are other poems in Optic Nerve about entoptic phenomena, musca depicta (flies in still life paintings), and the possibility of pinhole photos occurring naturally on other planets.

What’s next for you?

Here at the A-frame I’m working on new poems about walking, and wrestling with a little fiction. I’m also very much looking forward to some summer swimming when I get back to St John’s!

Optic Nerve is published by Brick Books ($22.95, 80 pages)