Foggy, Clearing up or Threatening Storm: What’s the Science of Weather in NL?

April 2017

Rain lashes the windows as I write this, and the snowbank outside has sunk an inch since I made my first cup of tea this morning. Yesterday the Environment Canada forecast for St. John’s was a big red brick, with a Freezing Rain Warning, Wind Warning and Rainfall Warning all stacked on top of a Special Weather Statement.

Until yesterday, I was blissfully unaware that freezing fog is a weather condition that apparently happens on Earth, and not just on planets in the outermost reaches of our solar system.

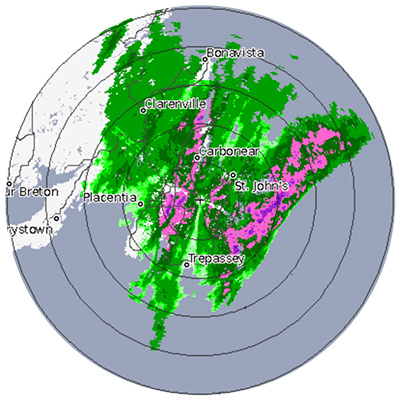

We’re officially ten days into spring, and at the moment the weather radar is doing its best to redecorate, garlanding the Avalon in bright spring colours. I like to call the radar the Pink, White and Green:

St. John’s is the foggiest, windiest, and cloudiest city in Canada, so it’s probably no surprise that #stormchips are now more important to the province’s economy than cod, an umbrella is a sure sign that someone is a CFA, and celebrity weatherman Ryan Snoddon is as much a meme as a meteorologist. We’re starving to know what the sky is up to, and we have countless ways to keep up: phone notifications, Twitter feeds, hourly radio updates, apps and websites, television channels, wall gadgets, watching to see what blows past the window, or the hopelessly oldfangled technique of poking your head outdoors.

A hundred years ago, our weather options were much more limited. In a 1913 Newfoundland Quarterly article titled “How We Get the Weather Forecast in Newfoundland,” William Campbell sought to explain to readers where the forecast came from. From his very first sentence — Everybody has nice things to say of the accuracy of the weather forecasts for Newfoundland — he describes a very different meteorological world than today.

Campbell describes how in the 1870s, at the top of Garrison Hill in St. John’s, there was an “apparatus for obtaining particulars of wind velocity, weight of the Atmosphere, etc., the result of which was filled in on a printed form and forwarded by mail to the Meteorological headquarters in Canada.”

This still happens today, as tourists coming from the Basilica often stand at the top of Garrison to snap photos of the harbour, and occasionally a gust of wind carries one all the way to Toronto.

“The public of Newfoundland derived no benefit from these reports,” Campbell notes, “until the past few years when regular weather report stations were opened at the Postal Telegraph offices at Port aux Basques, Burin, Fogo and Mrs. Higgins residence in St. John’s” (if Mrs. Higgins was around today, she would be all over #nlwx). Campbell continues:

Instruments are placed at these points and the observations obtained comprise the Barometric reading reduced to sea level, the temperature of the air, the maximum and minimum readings of the thermometer during the twenty-four hours, the kind of weather, the direction and force of the wind and the amount of snow or rain, if any. These observations are sent by a code which is translatable at sight and the whole observation can be deciphered in from three to four words.

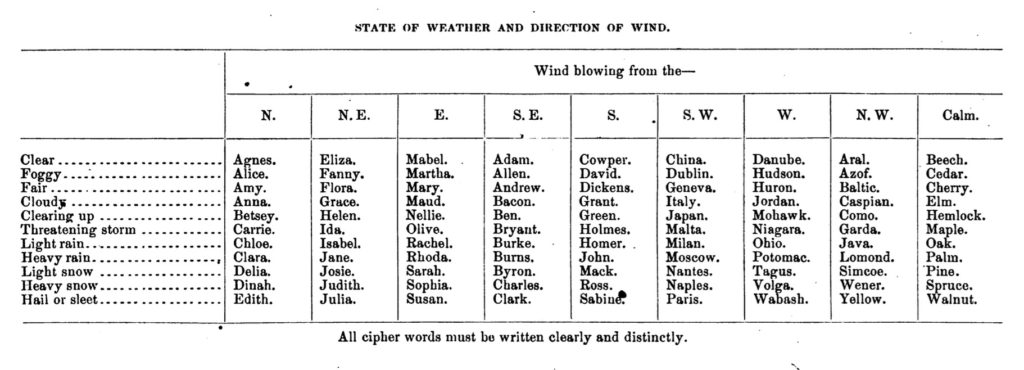

The article doesn’t go into detail about this, but I was curious about how complex weather data was telegraphed in “three or four words.” As it turns out, early telegraph operators used tables of miscellaneous words to encode complex information, since it was quicker and easier to transmit a single word than a long sentence.

Kind of like how, if a friend in BC texted me a photo of their garden and asked me how spring was coming along in St. John’s, I might just reply ⛄💩.

Here’s a table of cipher words used by the U.S. Army in the 1870s to telegraph the state and direction of wind:

From Cipher used for the telegraphic transmission of the weather reports of the Signal Service (1872)

So, for example, if you were a telegraph operator and you received the word Agnes (probably in Morse code), you were being told that wind was blowing from the North, and that it was clear. If you received Maple, it meant that the wind was calm, but there was a threatening storm. And if you received Maple Bacon… well, either the weather was quite a mess, or the operator on the other end was hungry.

People mostly found out about the weather through newspapers, although in From Telegraph to Internet — Canada’s Weather Service Since 1871, Environment Canada mentions some more innovative ways of getting out the forecast:

For farming communities along rail lines between Windsor and Halifax, an ingenious system was developed in 1884 to get the weather word out. After receiving a mooring dispatch from the central weather office in Toronto, railway agents affixed large metal discs (the shape depended on the approaching weather system) to the engine or baggage cars. To farmers working their fields, a full moon chugging by signalled sunny skies, a crescent moon meant showers, and a star meant prolonged rainy periods.

I love this idea and I think we should bring it back into service immediately, along with the entire Newfoundland Railway.

Advertisement from a 1929 issue of NQ.

Meteorology is a science, but there’s certainly a lot of art to it. Even a hundred years ago, weather forecasters caught flak from people who trusted their instincts more than a meteorologist’s crystal ball, as Campbell muses:

What perhaps surprises the official forecaster with his great charts before him and with his horizon so to speak thousands of miles away is the innate conceit of the everyday citizen who, looking around their little view of the horizon which possibly extends for ten or twenty miles, says “the forecast is all wrong, I am sure the weather is going to be so and so because the clock wound hard last night or for some other local sign.”

On the other hand, the article notes, “It has also been argued that as there is nothing but the sea to the Eastward of Newfoundland, from which direction the worst gales come, an accurate forecast cannot be given.”

It’s snowing now, and the weather radar has settled down a little. Although I haven’t left my desk, #nlwx tells me that St. John’s harbour has jammed up with ice, small icebergs are attacking reporters in Middle Cove, and there’s more weather on the way. ⛄💩!