False Armistice – November 7, 1918

November 2018

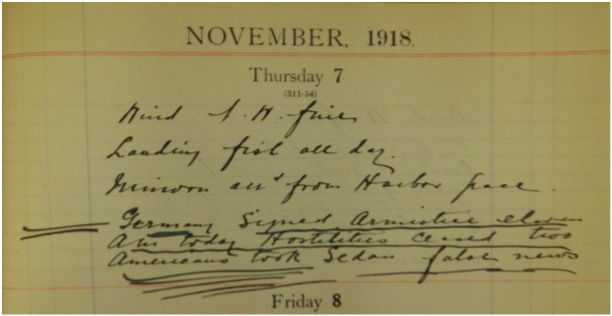

In a diary filled with weather reports, dockside activities (“screwing drums” and loading fish), and ship movements, the entry for November 7, 1918 would have stood out even if it had not been underlined with multiple strokes.

“Scribbling re weather…,”

Baine Johnston & Co. Ltd. fonds, Box 2J

The Rooms Provincial Archives

“Germany signed Armistice eleven am today. Hostilities ceased two. Americans took Sedan. false news.”

“Germany signed Armistice eleven am today. Hostilities ceased two. Americans took Sedan. false news.”

The exclamation of sheer joy literally leaps off the page, only slightly modified by the last two words which are understood in hindsight and may have been written later.

On November 7, an Armistice would have signalled the end of a war that had lasted from August 1, 1914 to November 7, 1918, 1,560 days – four years and three months. It would have signalled the end to a conflict that left millions of people, military and civilian, wounded, widowed, orphaned, or dead. On that day, without the luxury of hindsight, news that the war had ended led to jubilant celebrations not only in Newfoundland, but also in communities throughout the nations which had participated in the Allied effort. But it was a premature observance caused by a chain of events which led to the inaccurate declaration of the end of hostilities. There are variations on how these events unfolded, with all sharing the sentiment that the news was believed because people wanted to believe it. Those involved in the sequence of events included the American Army’s Intelligence Service, a Vice Admiral in the United States navy, and the president of the United Press (UP) organization.

In November 1918, there was a growing optimism that the war was winding down and would end soon. Turkey and Austria had signed peace agreements and victory against Germany seemed imminent. Anticipation was heightened on November 6 when there were reports that German delegates had crossed the front lines on their way to Paris to begin armistice negotiations with Marshal Ferdinand Foch, supreme commander of Allied forces. Events leading to the November 7 celebration began when staff of the American Intelligence Service read a German cablegram which had been intercepted. Misconstruing the message, which mentioned a cease fire, as a declaration of signing an armistice, they forwarded their “intelligence” which eventually made its way to the American embassy.

Someone, possibly a member of the embassy, passed the information to Admiral Henry Braid Wilson, commander of US naval forces in France whose headquarters were in Brest. Believing it to be official, Wilson shared the news with Roy W. Howard, president of UP, who happened to be visiting the vice admiral. According to UP procedures, all cables from France had to be signed by UP’s foreign editor William Philip Sims. Unfortunately, Sims was 591 km (367 mi) away in Paris and Howard was about to board a ship leaving Brest for the United States. Rather than lose the scoop of a lifetime, Howard allegedly forged Sims’ name to a cablegram sent to W. W. Hawkins UP’s general manager in New York City. As far as Hawkins was concerned the names of both Howard and Sims were sufficient to confirm its veracity. Besides, protocol required all telegraphed messages to pass American and French military censors before being sent. Hawkins didn’t realize that the censors had accepted Howard’s and Sims’ signatures as legitimate and cleared the communication.

At some point the French censors in Paris did order newspapers not to report what they rightly insisted was unconfirmed war news and instructed regional censors to block its transmission. It was too little, too late. Private telephones, military telegraph networks, and word-of-mouth, were beyond the censors’ reach, and the false news spread. In the United States, Secretary of State Robert Lansing denied the report, but no one wanted to believe that it was an error; by then the victory celebrations had begun and they would continue, unabated.

On November 7, UP released the contents of the cablegram to its subscribing newspapers, many of whom put out extra editions declaring WAR IS OVER. The Washington Times even boasted that it was “First with the news!”, claiming to be far in advance of any other paper, and probably the first in the country to make the news public. It certainly beat The New York Times which merely reported that the end of the war was near. In Canada, The Globe (predecessor of The Globe and Mail), unable to corroborate the story through their Washington and European reporters, refused to print the story. But, the Manitoba Free Press (predecessor to the Winnipeg Free Press) put out an extra edition declaring that an armistice had been signed.

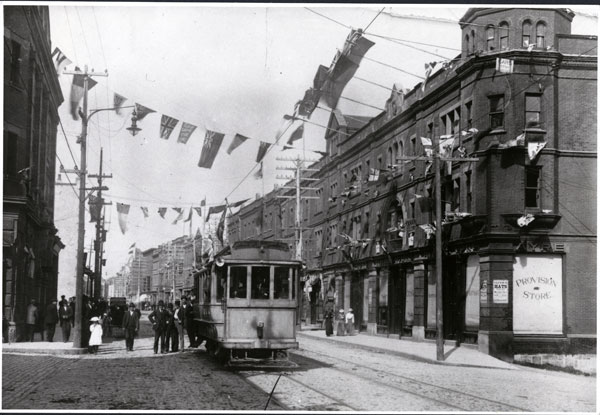

Water Street decorated for the end of W.W.I.

The Great War photograph collection, The Rooms Provincial Archives

Collection MG 110, Item A 42-113

Newspapers in St. John’s were as diverse in their coverage as were the foreign newspapers. The Evening Telegram and The Daily News had reports about the Hun standing hat in hand before Foch, while noting that nothing was yet final. On page one, The St. John’s Daily Star quoted a statement from London that had appeared in the Montreal Star, “Semi-official reports declare that Germany has decided to accept Foch’s terms for an armistice.” With less restraint, the paper’s page two headline shouted, “HUNS QUIT!”, based on a special despatch which had been received by F. B. McCurdy & Co., St. John’s bond and stock brokers. The despatch is dated at Paris, November 7, with no indication of who sent it.

At eleven o’clock this morning an armistice was signed between The Entente Allies and Germany and at two o’clock this afternoon hostilities ceased. Sedan was captured by the American forces before the truce between the belligerents was concluded.

Regardless of what the newspapers printed, the news spread, and celebrations burst forth in in St. John’s, Grand Falls, Corner Brook, and anywhere that it was heard. Festive decorations were hung, flags raised, and crowds gathered spontaneously to rejoice. In the words of one newspaper, St. John’s “was agog with excitement.” But, by the evening it was apparent that the news was premature and on November 8 newspapers were reporting the circumstances which had led to the announcement.

In a way, the false armistice was not all bad, the intensity with which it was received relieved the emotional tension that was growing as people waited on peace, while allowing people to start planning for the real armistice. The November 7 false armistice news was not the cruel hoax some believed it to be, nor a deliberate deception. Rather, it was a perfect storm of misinterpretation, misinformation, and mistaken priorities.

The real armistice agreement with Germany, signed on Monday, November 11, 1918, finally ended the First World War with a cease-fire starting at 11:00 a. m. (Paris time). It was the last of the September-November 1918 armistices between the belligerents and was celebrated with no less joy and cheer, no less emotion.