Clarence Birdseye Eats His Way Through Labrador

June 2017

OF ALL the animals Clarence Birdseye devoured during his three years in Labrador, lynx was the most memorable. “I arrived by dog team at the North West River,” he wrote, “and, after thawing out, sat down to one of the most scrumptious meals I ever ate. The pièce de résistance was lynx meat, which had been soaked for a month in sherry, pan-stewed, and served in a brown gravy.” It tasted even better than polar bear.

The ever-adventurous gourmet found himself far from home in 1912, having traded his Washington office for a berth on Wilfred Grenfell’s hospital ship. Hired to help establish fox farms, which he knew almost nothing about, Birdseye travelled to Labrador with his eyes open and his stomach grumbling. With the tricks he learned from the ice and the Inuit, he would later revolutionize the frozen-food industry, almost singlehandedly putting a freezer in every kitchen in America. Along the way, he stuck a fork in every wild animal he could find.

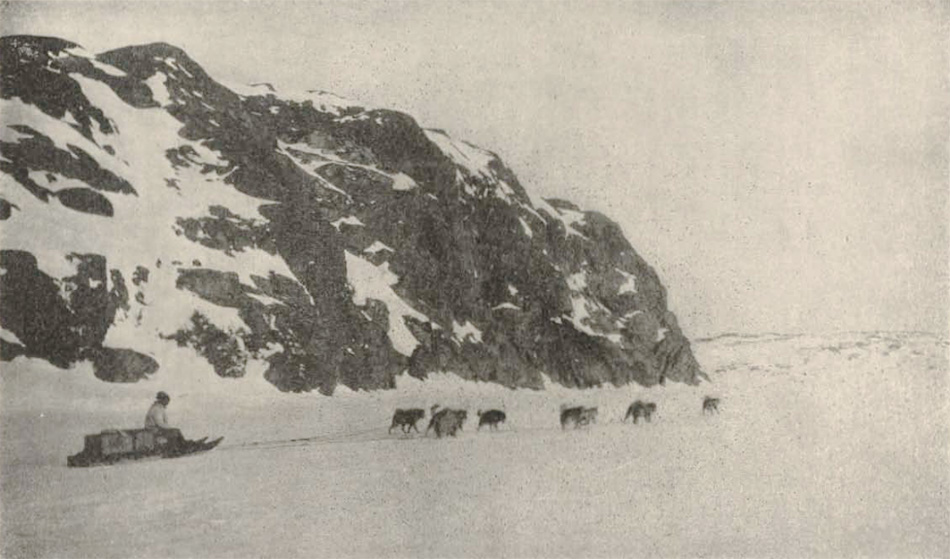

“My team, a live silver fox in the rear box,” from Birdseye’s 1914 article in Among the Deep Sea Fishers.

Growing up in Brooklyn, Birdseye loved cowboy stories and spent much of his time outdoors. “I guess I was some kind of naturalist from the time I could walk,” he later wrote. At ten years old he taught himself to stuff birds and rodents, mostly by pestering people in taxidermy shops, and trapped muskrats to buy himself a shotgun. In university he scrounged up tuition money by collecting rare rats for a biologist, and frogs for the Bronx Zoo. Characteristically inquisitive and entrepreneurial, willing to try anything, Birdseye once described himself as “just a guy with a very large bump of curiosity and a gambling instinct.”

He was also notoriously obsessed with food, especially wild game. Working for the U.S. Department of Agriculture in New Mexico and later Montana, he trapped and cooked field mice, chipmunks and gophers. Slices of rattlesnake fried in salt pork, according to Birdseye, “tasted much like frog’s legs.” He sampled porcupine, beaver, and woodchuck, and was particularly fond of “the front half of a skunk.” His menu also included winged creatures, from wild geese to hawks to great horned owl.

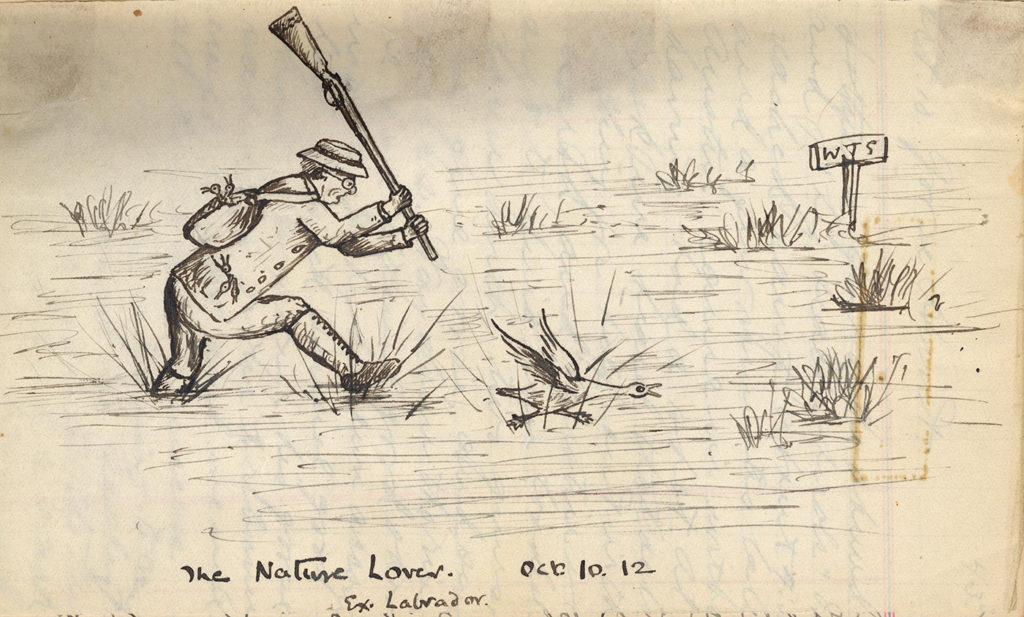

A caricature of Clarence Birdseye, “The Nature Lover,” drawn by Wilfred Grenfell (note Grenfell’s initials, WTG, on the signpost).

It’s perhaps not surprising that Birdseye was drawn to Wilfred Grenfell, Labrador’s medical missionary. After all, Grenfell’s many adventures included being marooned on an ice pan, where he fashioned a flagpole out of the legs of frozen sled dogs. “Mr. Clarence Birdseye, an expert naturalist, has left the department of zoology in Washington to try and foster a series of live fox farms for Labrador,” reported Grenfell in a 1912 issue of his newsletter, Among the Deep Sea Fishers. Birdseye initially accompanied Grenfell on a six-week tour of the Labrador coast, travelling by hospital ship, talking to fur traders and learning all he could about breeding and selling foxes. He returned the following spring, and in 1915 he and his wife Eleanor built a house in Muddy Bay, near Cartwright.

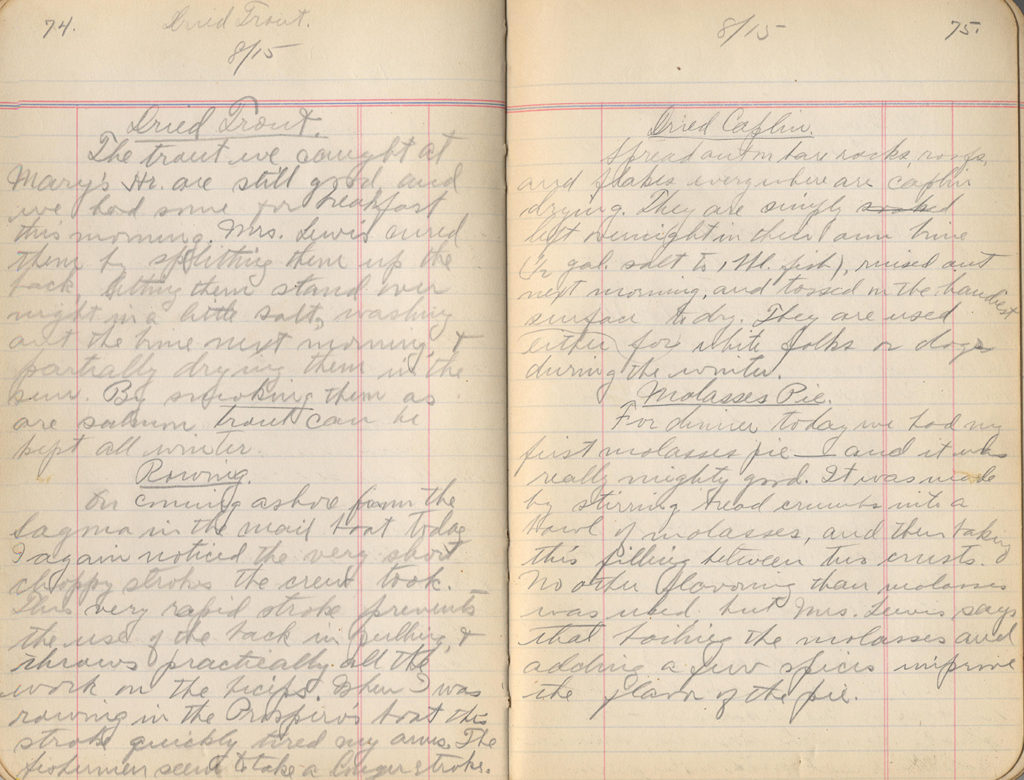

Birdseye thrived in Labrador. During the long northern nights – especially before he was joined by his wife – he wrote letters home and kept meticulous journals of his dogsled travels, fox-farming schemes, and everything he ate. A keen observer, he was especially fond of recording local recipes, and there are journal entries titled “Dried Trout,” “Dried Capelin,” “Fried Stewed Partridge,” and “Molasses Pie.”

A page from Birdseye’s Labrador journal, with recipes for Dried Trout, Dried Capelin, and Molasses Pie.

Birdseye also wrote for American magazines such as Outing, and his voracious appetite often seeped into his prose. In a 1914 article titled “Camping in a Labrador Snow-Hole” he describes being stranded for two days in a blizzard as “being lost in a flour-barrel,” and lists everything he ate during the ordeal, including rice and raisin pudding, salt codfish, bread and molasses, rice, prunes, candy (which he disliked, but kept on his sled to give to children), and a lunch of cocoa and fried partridge.

“A Valuable Meat Food for War-Times” is the somewhat unappetizing title of the single article that Birdseye published in Newfoundland Quarterly, in 1915. Proposing to ease wartime rationing by feeding soldiers seal and whale meat, he argues that it made both economic and gastronomic sense. “Many, perhaps most, people will consider the idea of eating seal or whale meat disgusting or absurd,” wrote Birdseye. “Yet it is neither. I have eaten most kinds of game to be found in North America, and consider that the flavour of none of them surpasses that of young ‘white-coat’ harp seal.” Describing young whale as tasting “much like beef and as tender as the best tenderloin,” Birdseye insists that its bad reputation is simply because people are eating animals that are too old. “The meat of old seals and old whales may be both strong and tough,” concedes Birdseye, “but so is that of old bulls, or of old stags or old bears.”

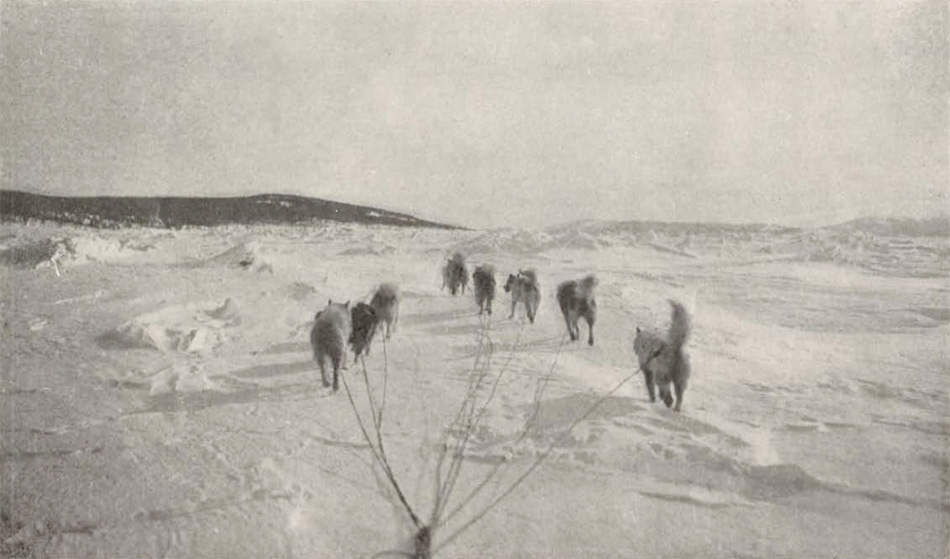

“My team doing business in a typical manner,” from Birdseye’s 1914 article in Among the Deep Sea Fishers.

In Labrador, Birdseye sampled otter, marten, muskrat, and numerous seabirds. “Good Lord,” he wrote in a letter, “how fine gull gravy tastes!” But it was his appetite for cod that would change American kitchens forever. He had noticed that fish solidified almost instantly in the -35°C air, marvelling that they were “frozen in mid-flip!” He had also observed that Inuit fishers stored their catch outdoors, thawing fish in water before cooking. Frozen fish in Labrador tasted fresher than any frozen fish he’d ever had in New York, and Birdseye was determined to find out why.

It was common knowledge in Labrador that food kept best when frozen during the coldest winter months. Comparing a fish frozen in midwinter to one frozen in spring, Birdseye noticed that the ice crystals were much smaller on more quickly-frozen fish. “When it snows on a mild winter day,” he later wrote, “the flakes are large, and on a cold day they will be small. It’s the same principle.” Birdseye theorized that smaller ice crystals were less damaging to food, helping to preserve flavour and freshness. He tested his theory by flash-freezing cabbages, and it worked wonderfully.

From here, Birdseye’s story reads like a case study from a business-school book. Upon returning to the U.S. he patented his techniques, founded a frozen-foods company, and in 1929 sold his business to Post for $23.5 million (the equivalent of about $300 million today). Birdseye continued to work for Post as a researcher and consultant. From 1929 to 1959, the percentage of American homes with a refrigerator went from 8% to 96%, and “Birds Eye Frosted Foods” became a household name.

Back in Labrador, the fox farms didn’t really work out, but Birdseye’s innovations certainly benefitted fishers, saving them from having to split and salt fish before selling it, and creating vast new markets for frozen seafood. “The value of their catch was more than doubled,” wrote Wilfred Grenfell in 1935. “Little did we think when that youthful student from Washington joined us in Labrador that his would be the honor and joy of being such a permanent blessing to the future.” So if there’s a freezer in your kitchen, you can thank Inuit tradition and Birdseye’s relentless appetite. Anyone who’s ever dropped icecubes in a drink can raise a glass to that.