Root Cellars and Flying Fish: the Bonavista Biennale

October 2017

Catherine Beaudette and Patricia Grattan made the solar eclipse happen. Well, not quite. But through a careful alignment of curatorial skill, community-building, and grant-wrangling, they put into motion something just as impressive – the inaugural Bonavista Biennale, which took place from August 17 to September 17, 2017.

Biennales happen in big cities: Venice, Istanbul, São Paulo, Berlin. So the idea of a ‘Bonavista Biennale’ sounds incongruous, something like proposing Woodstock at Woody Point, or an Olympics at Ochre Pit Cove. Nevertheless, thanks to two intrepid curators and their team, a constellation of contemporary art lit up the Bonavista peninsula this summer, with 26 artists from across Canada (about a third from Newfoundland & Labrador) installing work at sites from Trinity to Keels.

Living up to its promise of “art encounters on the edge,” a tour of the Biennale takes you to some out-of-the-way places. Laura St Pierre and Jon Bath have transformed a root cellar in Elliston into an eerie terrarium of bottled plants. Reinhard Reitzenstein’s inverted trees wave their roots like flags from the barachois in Knight’s Cove, while in nearby Duntara Marlene Creates’s wind-felled evergreens reveal their ages in a 136-year-old saltbox house. In Port Rexton, Pam Hall’s flour-sack fish swim through a blue sky, over a windswept field of raspberries. Other sites include a salt fish plant, a diminutive church, and a rocky lookout in Maberly.

From watercolour to steel sculpture, crochet to performance art, the work varies widely in media, but has in common an attentiveness to local materials and landscape. It’s clear that the curators paired artists and locations with careful consideration for the history and visual context of each site. This is especially evident in the way Doug Guildford’s crocheted forms seem so at home in the careworn Coaker Factory Building in Port Union, or the way Catherine Blackburn’s beadwork quietly interrogates colonial history in the Ye Matthew Legacy Centre in Bonavista.

I’m very grateful to have been asked to show work in the Biennale. As one of the artists, I spent several days there setting up my work (in an old schoolhouse in Bonavista) and meeting people. At a reception for the event sponsors at Fisher’s Loft in Port Rexton, John Fisher spoke about the importance of businesses supporting arts and culture. He also noted that this was the first time so many communities in the area have come together to work on a project of this scale. The Biennale has put the scaffolding in place for something more. There was genuine excitement in Fisher’s voice, and you can feel it in the air here – Bonavista is booming with new small businesses, there’s a new brewery in Port Rexton, and the recent Cultural Craft Festival in Port Union was a huge success. When people come together, things start to happen.

Perhaps that’s what art does best – it brings people together, sparks questions, conversation and connection. This is especially true of art that ventures out into the world, far from the safety of the gallery. If you want to bolt a steel replica of an antique chair onto a rock barely jutting out of the Atlantic, as Will Gill did in Maberly, you can’t do it from your studio. You have to spend time in the place, talk to locals, track down a fisherman who knows the water and the weather. You have to ask permission, ask people to trust you. It’s an exchange, and in this way public arts funding is absolutely an investment – in what a place can be, and what people can imagine together, or as Pam Hall puts it so succinctly in Bojan Fürst’s article for the current issue of NQ, in “the creative capacity of communities.”

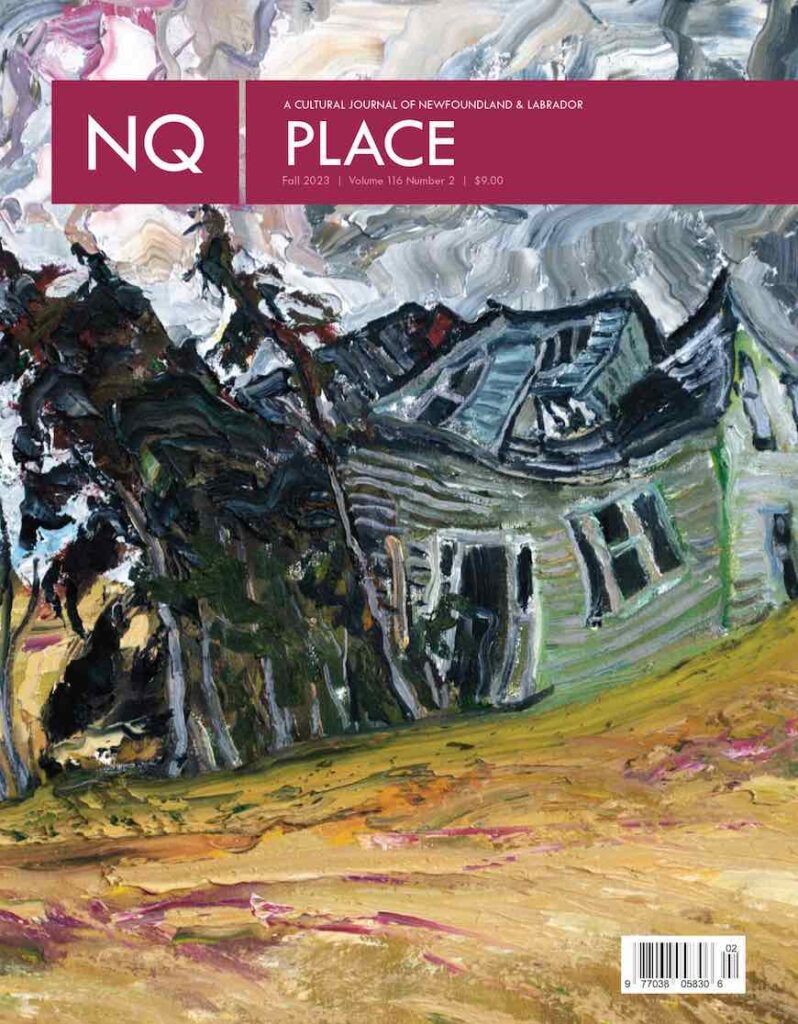

Pam Hall’s Bonavista Biennale installation in Port Rexton. Photo by Matthew Hollett.

Like the solar eclipse, site-specific art is something you have to see for yourself. Even videos don’t quite capture the thrill of Sarah Angelucci’s toy bird whistle performance transforming a tiny wooden church into a forest, or catching a glimpse of Pam Hall’s fish whirling over Devil’s Cove. It’s hard to understand that difference unless you’ve experienced it, and the Biennale has brought that experience to Bonavista and surrounding communities in a way that’s new, rare, and absolutely worth a visit. Go and see for yourself (the Biennale has ended, but Will Gill’s chair is still there) – if not this year, then two years from now, when hopefully everything all lines up for it again.