A Grand Time: NL Music at the Irish Traditional Music Archive in Dublin

BY Marie Stamp

July 2018

If you visit a certain elegant 18th century building in the heart of Dublin, you may still hear the voices of the dead. They chat and giggle and sing like happy, benevolent ghosts. There is nothing eerie about it… except that some of these ‘ghosts’ are from Newfoundland.

Unlike most visitors to 73 Merrion Square over the last 250 years, few Newfoundlanders would grapple confidently with the weight of the solid brass knocker that confronts you at the door. Few of our ancestors would have affiliated with the well-heeled former residents of this genteel urban neighbourhood. The Duke of Wellington was born around the corner, Oscar Wilde a few doors away. Yet, somehow, it has become home to the spirit of a little woman from St. Mary’s Bay in Newfoundland who died a quarter of a century ago.

By the time Theresa McCarthy of Mount Pearl arrived on that doorstep earlier this year, the hollow clang of that ancient brass knocker on its massive wooden door had long ceased to be relevant. An electronic buzzer was the medium that announced the arrival of Theresa and her sister to the current occupants: the Irish Traditional Music Archive (ITMA).

Inside, past the stylish fan-shaped window and slim classical columns, there is little evidence of the original inhabitants of this grand old brick house. Buzzing doors and tinkling cell phones, the hum of machines, footsteps muffled by carpet, and politely lowered voices greet the ear. The familiar white noise of a modern office takes the place of any whispering spirits that may have lingered. But Theresa McCarthy and her sister had indeed come to hear a ghost. They had come to hear their grandmother Ellen Emma Power, who died in Branch in Newfoundland in 1983.

Ellen Power (1893-1983) of Branch

This is the story of how that spirit was conjured up.

It begins in 1973. Aidan O’Hara was a young man from Donegal living in Dublin with his Canadian wife Joyce and their four children. An Irish scholar and singer, Aidan had been a teacher and a broadcaster. He had recently made a radio documentary about an Irish singer named Delia Murphy, who had lived in Canada as the wife of a diplomat. While researching Delia’s time in Canada, he came in touch with Dr. Kenneth Goldstein, who eventually become well-known for his extensive collection of Newfoundland folksongs.

Goldstein encouraged O’Hara to study at the Folklore Department of Memorial University of Newfoundland (MUN). Joyce O’Hara, herself a teacher and musician from Ontario, was delighted to go along with the idea. It would solidify their four children’s connection to Canada. The voyage was launched.

Once in St. John’s, it was not long before Professor John Mannion (a Galway man) introduced the O’Haras to the communities of Irish settlers on the Avalon. Aidan quickly joined the ranks of enthusiastic folklorists that were exploring our outports with their tape recorders in those days, but something about him was different.

Aidan O’Hara had made a career on the radio; he knew how to interview people and put them at ease in front of a microphone. He knew how to select the best equipment for the job and he knew how to use it. In short, he was a “pro”.

The people of our Province don’t always warm to the role of being a specimen for study by “pros” or anyone else. We’re not always happy about being asked to “perform” for people from “away” who are interested in our language, our accents and our humour. There are sensitivities. But O’Hara was different in this respect as well. He didn’t just record people. He joined in.

Joyce, who would eventually form her own recording company and publish an extensive series of CDs for children, accompanied him in a repertoire of beautifully harmonized folk songs. “Word would go out that we were coming” he chuckles, “and there’d be a ‘time’.” Clearly, it wasn’t always an academic exercise.

Aidan would eventually make hundreds of recordings of the stories and songs of the people he met in Newfoundland. He did not have to insist too much to coax them to take the mic. “Sing a song or hum a tune, do a dance or leave the room! That’s what they used to say,” he remembers of his time in Branch.

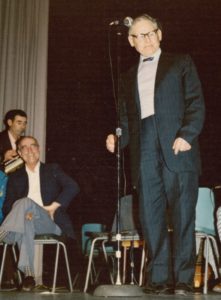

February, 1976: John Joe English & mbrs of the Branch Crowd perform at the MUN Little Theatre concert for O’Brien house.

Forty-five years ago, the people of Branch reacted to the arrival of their Irish guests in a way that might seem antiquated to us now. In 1973, in a remote fishing village poorly connected even by roads, transatlantic travel was something few people had achieved. For a remote community that had descended from Irish immigrants in the 1800s, being visited by people from modern Ireland must have felt a little bit like being found after a 200-year-old shipwreck. The welcome was effusive.

Charmed by the sound of familiar Irish accents and warmed to the heart by outport hospitality and friendship, O’Hara grew more enthusiastic about recording what he heard. The reels of tape would multiply until the family moved back to Dublin in 1978.

In 1980, Aidan returned to St. Mary’s Bay to film a documentary entitled “The Forgotten Irish”. This documentary made an enormous impression on audiences in Ireland and infused the people of Branch with a new sense of pride. Aidan believes that by sharing their Irishness with Ireland, the small community reaffirmed itself and became more determined to survive its economic distress.

Gerald Campbell (with cup) and Albert Roche of Branch.

Aidan donated a significant portion of his collection to the MUN Folklore Archives, where it continues to be studied. The Newfoundland and Labrador Folk Arts Society is recognizing this contribution in a lifetime achievement award at the 2018 Folk Festival.

Hundreds of other recordings travelled back with him to Ireland. Tapes disintegrate over time, and Aidan began to be concerned about conservation as well as the preservation of his collection. When the ITMA was founded in the late 1980s, Aidan offered it to them.

Let us now “fast-forward”, pun intended, to 2017 and the arrival of another pair of feet from Newfoundland on those impressive steps at Merrion Square. Dr. Rebecca Draisey-Collishaw had moved to Dublin from St. John’s, where she had just earned her PhD in Folklore from MUN.

“She was the right person at the right time,” says Grace Toland, the Donegal-born director of the ITMA. Both women agreed that the O’Hara collection was of tremendous value and interest. They began to work on a project to make it more accessible. The result: a ‘digital exhibition’ entitled “A Grand Time”, to be launched on the ITMA website on the 1st of August 2018, will project voices from Newfoundland onto the world stage.

The exhibition will tell the story of the connection between Newfoundland and Ireland, present a history of the recorded collections and a video interview with Aidan O’Hara. A number of the original recordings themselves will be available for listening, accompanied by photos and specially commissioned historical maps. It will also include information about the songs, biographies about the performers, and bibliographies and downloadable songsheets.

Grace Toland has ensured that the exhibition is curated with the greatest respect. The ITMA is home to over 37,000 sound recordings, nearly as many printed collections, and tens of thousands of photos and other items. Musicians, singers, historians and the curious from around the world visit or login by the thousands to consult them. Toland regards her stewardship of the archives as a labour of love. She sees

the Newfoundland collection in her care as a particular honour, and she wants us to know it. “I do hope they see that this is the right home,” she tells me, “I hope they feel it has ended up in the right hands.”

And now to close this Irish loop.

Rebecca Draisey-Collishaw got in touch with people back in Branch to let them know about the digital exhibition at the ITMA, and the news reached the ears of Theresa McCarthy as she was preparing her Irish holiday. Theresa (née Nash) was raised in Branch, and her grandmother Ellen Emma Power (1893-1983) is one of the singers who will feature on the ITMA’s website.

Theresa determined to visit the ITMA with her sister during their upcoming trip. Rebecca was delighted to welcome them, and to play their grandmother’s recording. It was an emotional encounter.

Not only was Ellen Emma a much-loved grandmother, but her daughter – Theresa’s mother – had inherited her voice. Theresa’s mother, who died in 2006, had learned to sing those songs in exactly the same way. The two sounded so similar, that both women seemed to come to life again at the simple click of a button. Stunned, delighted, and full of tears, the two women burst with feeling as the room was flooded with that maternal voice.

But there was something new. The familiar Branch accent they had grown up with was only ever a Newfoundland accent, and neither of the women had reckoned with how Irish it really sounded. Hearing it now in Ireland felt like a surreal kind of homecoming.

As the voice of her grandmother was carried off onto the Dublin breeze, a strange thought occurred to Theresa for the first time. This is where Ellen Emma Power belonged. “This is where she’d want to be,” Theresa told me. “She is home. Her voice is home.”

“A Grand Time” is being launched with three special homecoming events – at the Branch Community Centre at 7pm on 1st August, at The Rooms in St. John’s at 2:30pm on 2nd August, and at the Oral Traditions Tent of the NL Folk Festival in St. John’s on 4th August at 1pm. For detailed info, go to https://www.itma.ie/events/a-grand-time-in-nl