Souvenir Shopping with Smallwood: Newfoundland and Expo 67

May 2017

“I’M A SORT of tourist attraction,” Joey Smallwood quipped, late in his career. “Everyone who comes here wants to meet me.” Having cajoled Newfoundland into joining Canada with promises of progress and baby bonuses, he was famously dubbed the “only living Father of Confederation.” By 1967 Smallwood had spent almost 20 years trying to industrialize the province, building everything from hydro dams to chocolate factories, determined to drag Newfoundlanders into the twentieth century. It’s no wonder he was so enchanted by the flashy internationalism and architectural extravagance of Expo 67, Montreal’s celebration of Canada’s Centennial.

A Smaller, Shinier Island

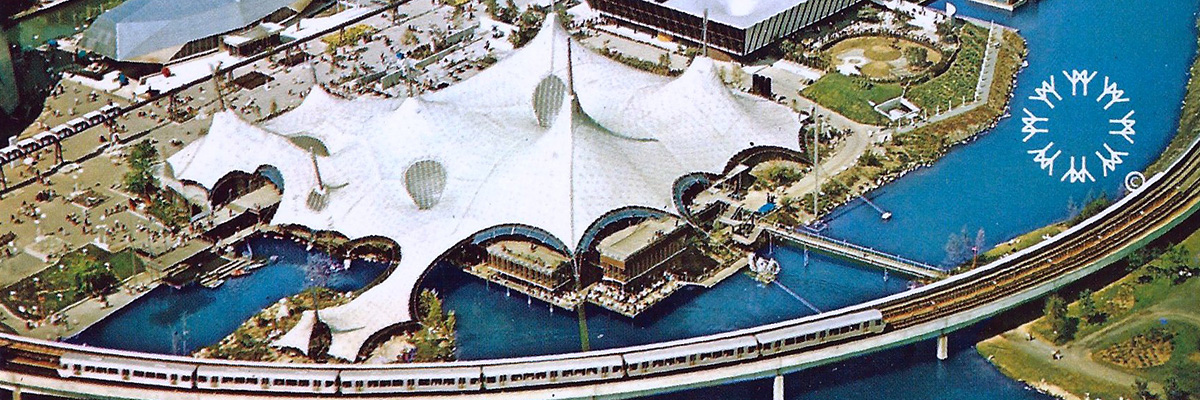

In aerial photos, Expo looks like an architect’s sketchbook sprung to life, with buildings shaped like spheres, inverted pyramids, and origami caterpillars. Whimsically cosmopolitan, bursting with the boundless techno-optimism of a world on the brink of the first moon landing, Expo’s futuristic fairgrounds attracted over 50 million visitors from April to October 1967. Canada’s population was only 20 million at the time. Fifty years later, it’s still the most successful World’s Fair.

From Canada’s ashtray-inspired pavilion to the Asbestos Plaza, it was all very Mad Men. Monorails zipped visitors to 90 pavilions representing dozens of countries, where they were treated to Space Age showrooms, multi-screen and interactive movies, music and theatre, and occasional sightings of celebrities such as Jackie Kennedy, Thelonious Monk and Yuri Gagarin. Smallwood, a visionary and a showman, would have felt right at home.

Even the site itself was shiny and new, having been constructed on an artificial island in the St. Lawrence River. While Expo 67’s freewheeling modernism might seem naive or even paternalistic today, it helped shape the international reputation of Canada, Quebec, and especially Montreal. Its architectural legacy includes the iconic Biosphère, Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, the Montreal Casino, and Parc Jean-Drapeau, and its success paved the way for the city to host the 1976 Summer Olympics.

Newfoundland’s presence at Expo was minimal. The four Atlantic provinces shared a schooner-shaped pavilion, Atlantica, which included a chowder bar, a boatbuilding demonstration, and a Viking longboat assembled out of whale bones from Trinity Bay:

“Whale Wall” by Witold Kuryllowicz and John Schreiber was an arrangement of whale bones in the shape of a Viking ship, part of the Atlantica pavilion at Expo.

Juxtaposed against the monorail overhead, our whale-boat looks more than a little kitsch. In any case, Expo’s grand modernist vision captivated Smallwood, who flew his entire family to Montreal for a visit. It wasn’t long before he began shopping for souvenirs.

Little Pieces of Eastern Europe

One of Expo’s most popular attractions was the Czechoslovakian pavilion, in part because of Kinoautomat, the world’s first interactive movie. At certain points during the film, audiences were invited to vote on which scene should happen next, but the movie always ended the same way – with a building on fire. It was intended as a satire on democracy, although I’m not sure Smallwood would have gotten the joke.

On September 5, 1967, at Gander International Airport, a Czechoslovakian airliner crashed on takeoff, killing 37 of the 69 people on board. By complete coincidence, Smallwood’s government had been negotiating with Czechoslovakia to purchase their Expo pavilion after the fair ended. In appreciation of rescue efforts by the people of Gander and Grand Falls, Czechoslovakia instead presented the structure to the province as a gift. It became the Grand Falls Arts and Culture Centre, now the Gordon Pinsent Centre for the Arts, and still contains artworks from the original pavilion. Part of it was also incorporated into the Arts and Culture Centre in Gander.

The Czechoslovakian pavilion at Expo 67, and today in Grand Falls-Windsor.

Photo courtesy of Jillian Parsons.

The interactive movie apparently didn’t come with the building, but Smallwood did acquire a large fountain that had been a centrepiece of the Pavilion. Designed by glass artist Bohumil Elias, it was incorporated into the lobby of the Sir Richard Squires Building in Corner Brook. The glass fountain collected coins and wishes for forty years, until in 2011 the Department of Transportation and Works tried to get rid of it, citing safety concerns. Thanks to a successful social media campaign, the fountain is still there, although it’s been placed behind a glass barrier.

Smallwood didn’t stop at Czechoslovakia. His government also arranged to purchase the Yugoslavian pavilion, a formidable triangular edifice that was converted into the Provincial Seamen’s Museum in Grand Bank.

The Yugoslavian pavilion at Expo 67, and today in Grand Bank.

After Expo ended, both pavilions were dismantled, shipped from Montreal to Botwood, and trucked across the island. Although neither had been designed to be moveable, and they required extensive retrofitting and winterization, both are still in use today.

Dandelion Seeds

In 2004, I moved to Montreal after completing the Visual Arts program in Corner Brook. I spent a lot of time exploring the city with my camera (see previously on NQ), especially the narrow streets and quays of the Old Port. Intrigued by the distant silhouettes of Alexander Calder’s massive L’Homme sculpture and Habitat 67, I took the metro to Saint Helen’s and Notre Dame islands to look around. The islands that hosted Expo 67 are now part of Parc Jean-Drapeau, named after the mayor who spearheaded the fair.

What I remember most is how empty it was. From the moment I stepped out of the metro, I seemed to be the only one on the island. Granted, it was late October, and the park is mostly used in the summer and for special events. But it was hard to imagine that millions of people had once milled through, or that monorails once whizzed overhead. Aside from the artificial island itself, the most prominent remnant of Expo is Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome. Originally the American pavilion, it survived a spectacular fire, and is now an environmental museum called the Biosphère. Inspired by its geometry, I lay on the grass to align a dandelion with its sphere, and took this photo:

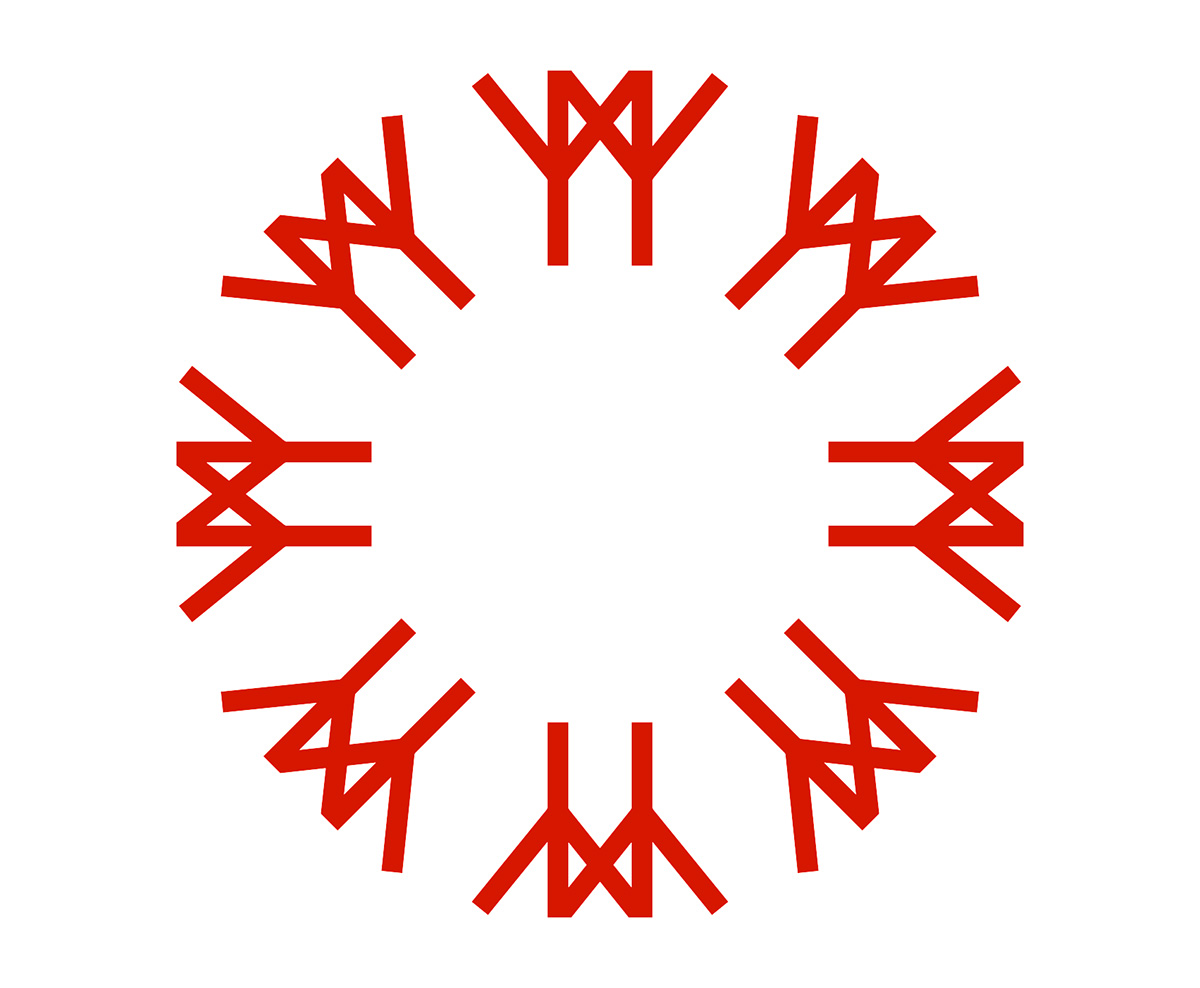

A few months later, visiting a graphic design exhibition at the Canadian Centre for Architecture, I was struck by how much Expo 67’s logo looks like a dandelion clock. Perhaps it’s not surprising that a few seeds of Expo’s momentous internationalism found their way as far east as Corner Brook, Grand Falls and Grand Bank.

Perhaps it’s also not surprising that Smallwood, who famously shmoozed with Fidel Castro and told post-confederation fishermen to burn their boats, chose Eastern European buildings as his Expo souvenirs. Any other politician in Newfoundland history, you can be sure, would have sprung for the whale-skeleton boat.