Seeing Through Glass, Plastic and Ice

April 2017

When I signed up for my first photography class in art school, my dad rummaged around in the basement and placed a heavy leather case in my hands. I unbuckled it to find his old 35mm camera, a Zenit EM, an indestructible Russian-built contraption. It had an enormous dent above the lens, as if it had deflected a bullet, and its selenium light meter, mysteriously, did not require batteries.

For months and years afterwards I wandered all around the trails and roadsides that defined the edges of my small town, seeing everything with new eyes: bright ice against a black brook, a handful of hollow reeds at Pasadena Beach, a dead dragonfly with wings like stained glass.

Photography swallowed me whole. The Zenit wasn’t quite my first camera, but it was by my side as I learned how to process film, mix darkroom chemicals, and make prints from my negatives. I learned film photography in the early 2000s, just as digital cameras were threatening it with obsolescence. By the time I finished my Visual Arts degree I had a digital camera and a photoblog and haven’t really looked back. But I’m happy to have learned how to think photographically through the quirks and constraints of darkrooms and black & white film.

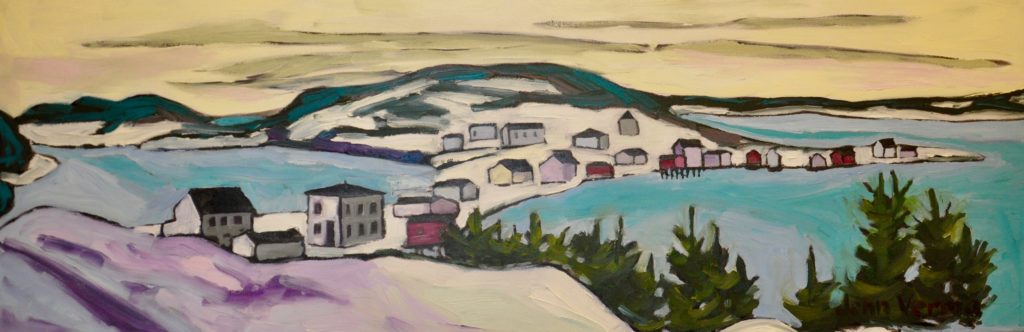

Tooton’s photography studio and shop opened in 1905, and was a staple on Water Street for ninety years. Its founder, Anthony Maurice Tooton, arrived in St. John’s from Syria in 1904. Tooton’s advertisements for cameras, film development and photo albums are some of the most beautifully illustrated in Newfoundland Quarterly in the 1910s and 1920s. In response, I thought I’d write about cameras I’ve owned, cameras that have been as essential as my contact lenses in shaping how I see the world.

If you’re thirty years or older you’ll likely remember how futuristic your first digital camera felt—clicking a button and instantly seeing the image seemed magical, even if the screen was smaller than a postage stamp. My first digital point-and-shoot was a Canon PowerShot a300 that I bought at the Valley Mall. I carried it with me everywhere in Corner Brook and in the halls of the Fine Arts building, started a photoblog and posted a photo every single day for a year and a half. Years later, as an art project, I digitally stitched together the first line of pixels from every photograph I ever took with that camera (5197 of them).

Later, in Montreal, I was nudged back into film when a Holga arrived in the mail from Massachusetts, a gift from a stranger who had stumbled across my photoblog. A toy camera, a Holga is little more than a plastic box with a plastic lens, and no matter how much I wrapped it in electrical tape, light always seemed to leak in one corner. Shortly after it arrived I moved to Halifax, and took it for long walks along the shipyard and railroad tracks, photographing colourful stacks of shipping containers, deep shadows beneath trestles, rails careening off to the horizon. A plastic lens has a way of making clouds cloudier, distance more distant, light more light. Even the flares caused by light leaks add a certain dreaminess.

In an antique store in Halifax I lucked into a Yashica-Mat LM, a twin-lens reflex that I still like to keep near my desk. It’s quite a character, a stout, serious camera with twin lenses like thick spectacles. It lifts its lens hood as if tipping its hat. It is observant, but slightly farsighted, and keeps a minimum distance of 3.2 feet from the subject of its scrutiny. It is polite to the point of being reticent, and a bit of a pessimist. Old-fashioned and opinionated, it relishes overcast days in autumn. It likes books without pictures, or books with nothing but pictures, but not both at the same time.

I remember how baffling it was to learn to use the Yashica. Taking a photograph involves a lot of fussing and adjusting. Its lens fails to focus on anything that isn’t at least three feet away. Its viewfinder shows a mirror image, so framing something feels a little like parallel parking. And in those days before Instagram, I wasn’t used to thinking in squares. But somehow all its little eccentricities turned into possibilities, and the camera became a crystal ball cupped in my hands.

Aside from those few experiments with the Holga and Yashica, though, I’ve mostly translated my surroundings into pixels, not film grains. My point-and-shoot gave way to a digital SLR, a Canon Rebel XT that I bought when I was still in Montreal. I’d sling it over my shoulder and seek out the far corners of Parc Mont Royal, or the quiet openness of the Old Port in winter. Along with my camera I started carrying a notebook, and I’d scribble bits and pieces of poems as I strolled. I was reading a lot of Thoreau and Bashō, seeking wisdom in walking and solitude, trying to be a kind of wandering observer of the world.

Today both camera and notebook have been replaced, for better or for worse, by my smartphone. But I still habitually walk, write things down and snap photos, and photography and poetry are intertwined forever in my brain. Here’s a poem along those lines, reworked from something I wrote in Montreal in 2005:

Morning Has Broken

In December the Saint Lawrence is a mirror

smashed over and over, a sharp-edged puzzle

of pack ice solving and dissolving itself

nightly, as if never quite satisfied

with the way it’s reflected the sky.

Bright sun jangles the dockside like a keychain

as I walk from quay to quay, photographing

the ice with its frivolous bird-footprint ballets,

crumpled paper clouds, and five Japanese tourists

who ask me to take their picture.

There’s no one else around, and from the belvedere

I can follow my footsteps all the way across the snow,

from the boardwalk’s far corner to the fresh impressions

hiding under my boots. Snow is the river’s

short-term memory, an emulsion I’ve left shadows in:

There’s where I backtracked when the sun broke

through the clouds, there’s where I almost lost

a lens cap, there’s where the tourists posed

in a row, and there’s where a dizzy seagull

seems to have disappeared