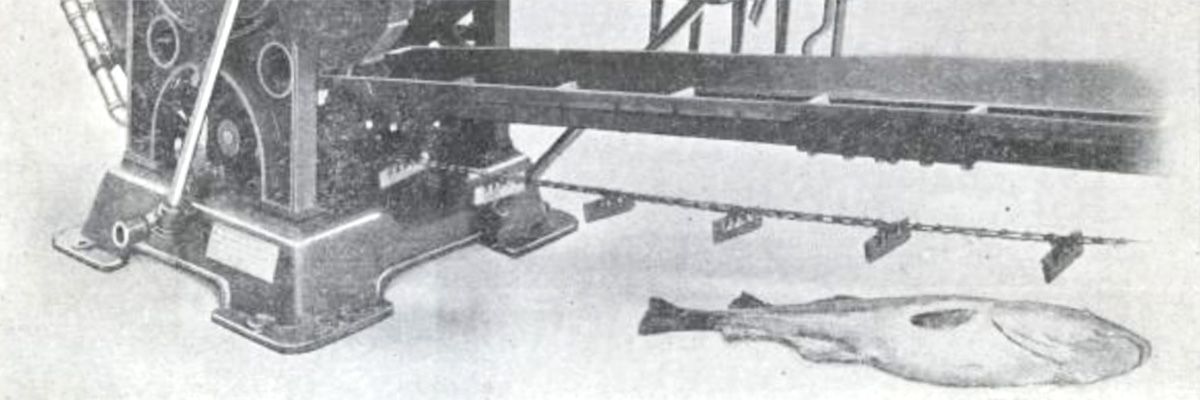

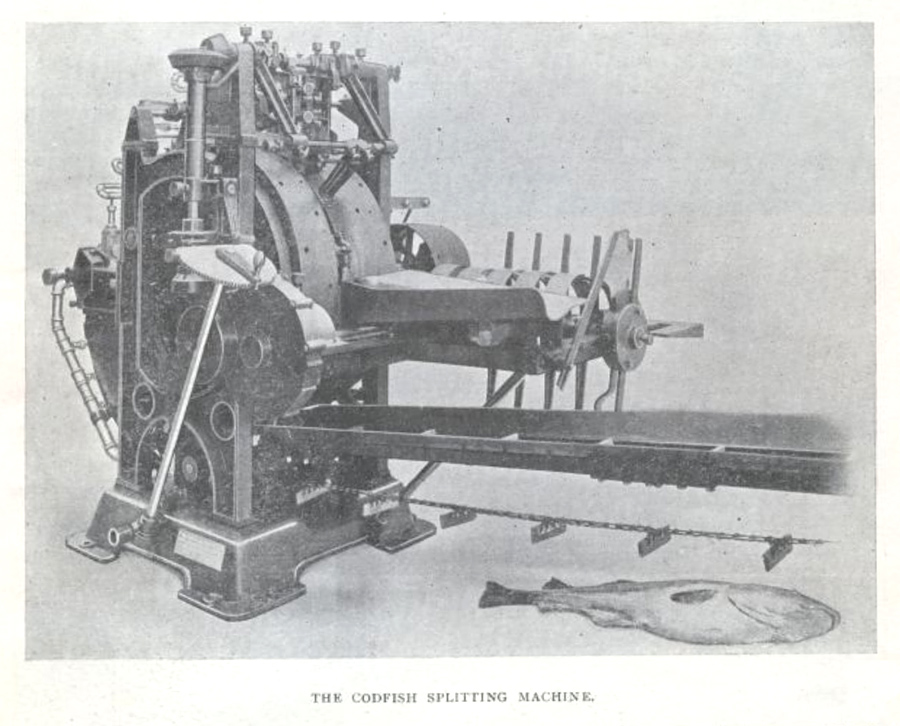

The Codfish Splitting Machine

April 2017

IN THE FALL 1922 ISSUE of Newfoundland Quarterly, anchored between a lament for the drowning of a local businessman and a brief history of Puerto Rico, I found a curious article titled “The Iron Splitter for Dressing Codfish.”

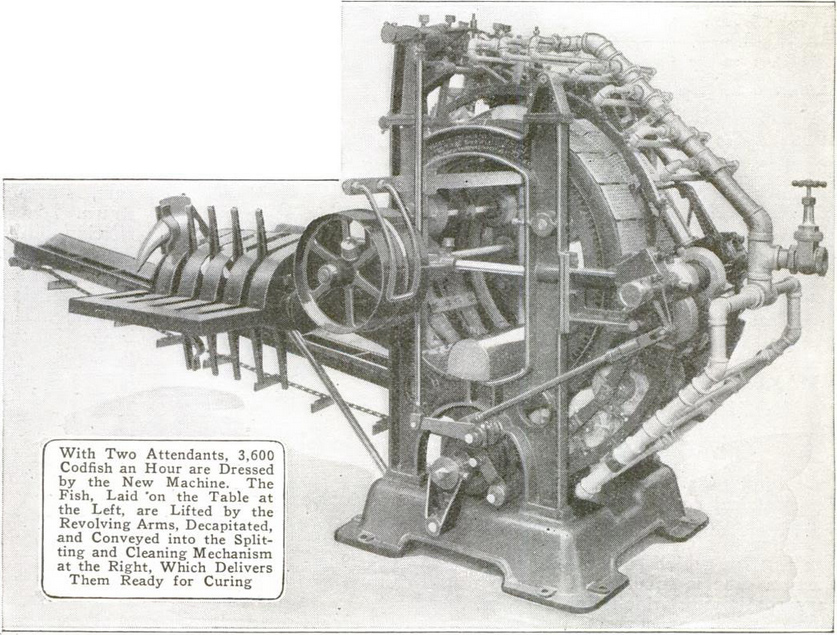

Its anonymous author salivates over the wondrous machines that were then transforming fisheries around the world. “On the Pacific coast of America the salmon which swarm up the river for a week or two each spring are transferred by the million into cans almost before they have time to look surprised,” they explain, “and all by machinery; the product reaches the consumer untouched by human hands.”

A description of the salmon-canning machine follows:

It consists, in outline, of a sort of revolving drum, round which the fish is dragged by its tail, meeting on the circuit with saws, knives and other devices which perform the various operations.

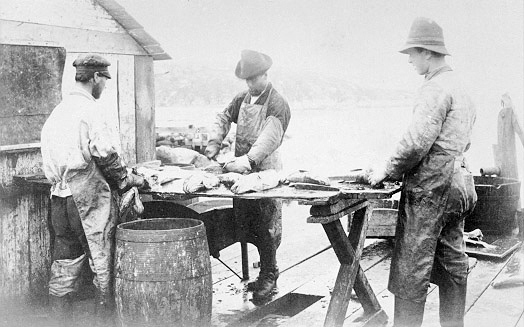

In the 1920s, codfish in Newfoundland were still processed much as they had been since the 1800s. “The staple industry of Newfoundland has stood still. There has been no advance in methods for the past four hundred years,” laments the author, who writes under a rather unimaginative pseudonym:

As “Progress” tells it, around 1917 a company in St. John’s, Job Brothers & Co., asked the manufacturer of the salmon-canning machines whether a similar device might be designed to process cod. The result, after years of prototyping and fine-tuning, was the codfish splitting machine.

A Popular Mechanics article from May 1921 trumpeting the same codfish splitter describes the machine’s convolutions:

“The cod are placed on the table of the machine and arms lift them through an odd-shaped concave knife, which severs the head. They are then dropped in a trough, where talons on a revolving drum grasp and drag them through a splitting saw, which scoops out the entrails, and through a cutter that removes the backbone as far as the vent; then they go down through a series of cotton-faced washing rolls, which remove the slime, finally delivering them, ready for drying or salting, to a conveyor near the point where they first went into the machine.”

It’s interesting to compare these detached, mechanical descriptions with the language of someone describing splitting a fish by hand (which I found in a 1996 MUN thesis called Making Fish). There’s a kind of loving precision in the hand-splitting instructions. Rather than the fish moving through a machine, we move through the fish, almost as if it is a landscape:

“The splitter holds the fish by the “vin” with his left hand, against a small stick nailed to the table. The stick helps to keep the fish in place as the necessary cutting is done. He enters the splitting knife, on the side of the sound bone furthest away from him, at the point where the head came from the body. From here a cut is made, at the depth of the bone, right back to the tail, slicing the fish so that it lies open flat all the way. Then the fish is held by the sound-bone and the bone is cut at about the middle and the tip of the knife is moved back up the fish and the bone is removed completely. The fish then drops into a puncheon tub of water, right below the splitter’s hands where it is washed before salting.”

Back to NQ and its cod-carving robot of the 1920s future:

“On one day thirty-five thousand fish were put through the machine, which means an average of fifty fish a minute for twelve hours continuous running. How many men it would take to get through this amount of fish by hand can be left for those interested in the fishery to calculate. It is no longer necessary to work by torchlight far into the night and rise again at daylight to finish the fish before it gets stale.”

“The machine dresses the fish swiftly, uniformly and untiringly as long and as fast as successive gangs can feed it. It has no need for meals or sleep; it finds no difficulty in the flickering torchlight; its knife never slips through weariness, to leave a “round tail.” The last fish comes out exactly like the first, and indistinguishable from the work of any but the oldest and most skilful hand-worker.”

I love the image of the codfish splitting machine labouring away “in the flickering torchlight.” There’s something so quaint about it… especially compared with what fish splitting looks like today.