The Southside Hills in History and Song

April 2017

I’M NOT SURE who first referred to them as the “Dear Old” Southside Hills, or if anyone still calls them that. Possibly the name went out of fashion when the huge oil tanks were built. But the nickname seems to have stuck for a while in the early 1900s, a curious term of affection for the imposing hillside that gives shape to St. John’s Harbour.

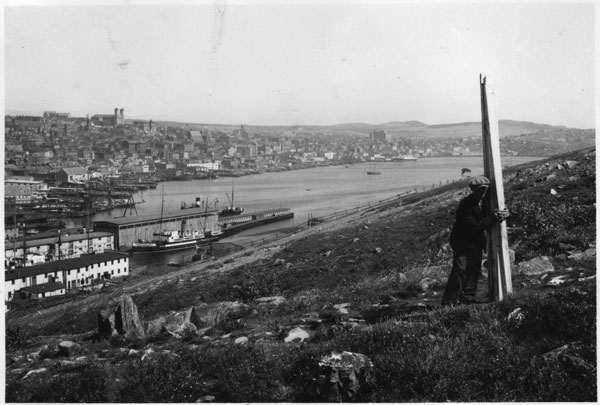

Southside, St. John’s. View of the Fort Amherst area with the harbour in the foreground (undated, from MUN DAI).

The term of endearment may have been popularized by M.F. Howley, a regular contributor to early issues of Newfoundland Quarterly. Later made Archbishop, he was “Rt. Rev. Bishop Howley” when he wrote Dear Old South-side Hill, a song printed in one of the earliest issues of NQ (March 1902). Here’s an excerpt:

I love each nook, each darling brook,

Each copse of russet brown,

Each gulley, pond and laughing brook,

That tumbles rattling down.

I love thee bathed in summer sun,

With opal light aglow,

Or robed in wintry garment, spun

From wool of silken snow.

Chorus:

Oh, dear old South-side hill,

Old rugged, scraggy hill,

I look with pride on thy sun-brown side

Oh, dear old South side hill!

Dear Old South-side Hill was “sung by Mrs. Harris at the C.C.C. ‘At Home’ with much success,” notes the magazine. The song was obviously appreciated, as just a couple of issues later NQ published a thank-you note from a reader in Boston. “This touches my heart,” wrote W.J. Carey, “as when I was a little boy at school the windows of the school-room of the old Orphan Asylum faced the hill. There was nothing to obstruct the view, and, of course, it was always the grand object of our scrutiny — even at our studies.” Carey even included a poem of his own, titled South-Side Hill, although it’s more about Howley’s song than the topography.

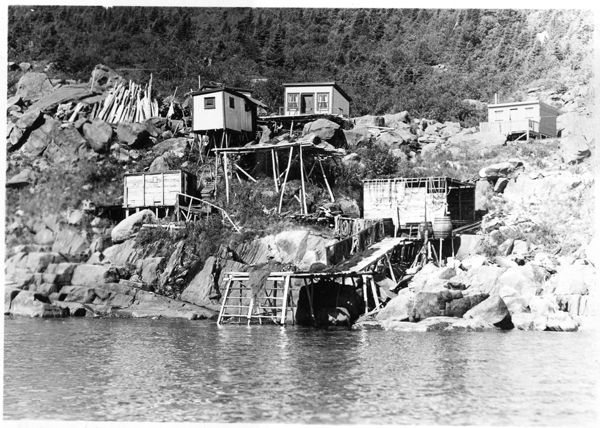

Houses and fish flakes, Southside, St. John’s Harbour, June 1893 (from The Rooms Archives).

In the December 1903 issue of NQ, as part of an article by H.W. LeMessurier called Ancient St. John’s, there’s a wonderfully detailed description of the Southside Hills from the 1800s (as a side note, LeMessurier himself is the songwriter of The Ryans and the Pittmans, or We’ll Rant and We’ll Roar).

“I propose to quote from a work called Family Recollections,” writes LeMessurier, “written by Miss Durnford, the daughter of Lieut.-Col. Durnford of the Royal Engineers, who was stationed here at the beginning of the nineteenth century.” Family Recollections was published in 1863. Here is the eloquent and precise Mary Durnford:

“Approaching Newfoundland we were at once greeted by a fragrant land smell, and soon the abrupt features of its wild fir-clad shores come in view.

The heights over-looking the entrance to Saint John’s are covered, almost from water-line to summit, with fir and spruce, and planted with batteries romantically situated. The raging surf of the Atlantic’s billows dashes against the embrasures of Amherst and Chain Rock Batteries; lobsters of the finest flavour, and other shell-fish are found in abundance amid the crevices of their shelving and slippery rocks, with hosts of mollusca.

Generally wherever the ground was laid open by clearance, the kalmia sprang up, an indigenous shrub or weed, brightening the wilderness with its pink clusters. Fantastic and delicate creepers present a trellised carpet to the feet that tread within the sombre shade of the woods; and varieties of graceful shrubs produce spontaneously the cranberry or oxycoccus, whose indian name is maskigo meino; the whortleberry or vaccinium; the partridge or mitchella, whose tiny wreath almost vies in beauty with that of the famed capillaire or linnæ, yet without the fragrance of the last; and the hardy little dogwood or cornus. There is much to admire in the decoration of its hills and valleys, its ferns and intricacies of wreathing foliage, clinging to and twining round tapering firs and valuable spruce trees. The beautiful white moss crushes beneath the feet, and another species hangs in tufts among the branches.”

Durnford might have enjoyed the company of the anonymous “Member of the Littledate Literary Club” who wrote about an autumn field trip to the Hills, published in the December 1906 issue of NQ. Her description of the view from the Southside brings to life just how much the city’s landscape has changed in 100 years:

To the north, the eye travels through vistas of shadowy fir trees to undulating pasture fields with cattle peacefully grazing in the sunshine. To describe this scene, or even to attempt such a description is beyond my skill, and far beyond my presumption; but I should like to convey some faint idea of its beauty — so brilliant was the foliage, so silvery and sparkling the river, meandering through the verdant slopes, so bright the sunshine and so exquisitely beautiful the whole stretch of country lying north, west and east. As we gaze with rapture, a tiny grey cloud seems to curl around the distant hill; presently it increases, until a soft, thick, white, fleecy cloud moves quickly and gracefully on, and very soon we are aware of the approach of the incoming train.

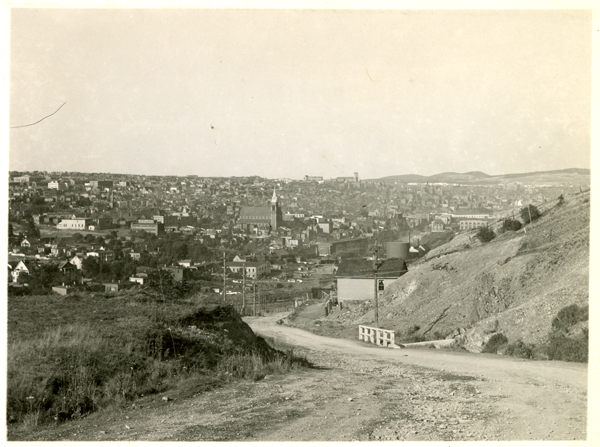

View of the Southside Hills and the west end of the harbour (undated, from MUN DAI).

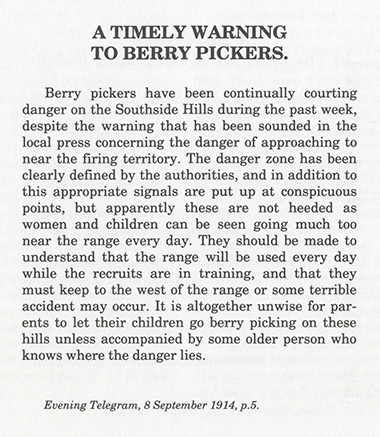

Anyone in St. John’s who picks blueberries has probably ventured up the Fort Amherst Trail packing a yogurt container or two. During the First World War, to the dismay of local berrypickers, part of the Southside Hills were turned into a rifle-training range. Notices were posted in the newspapers warning that the area was off-limits:

A notice from the Evening Telegram, 8 September 1914, as published in The Trail of the Caribou.

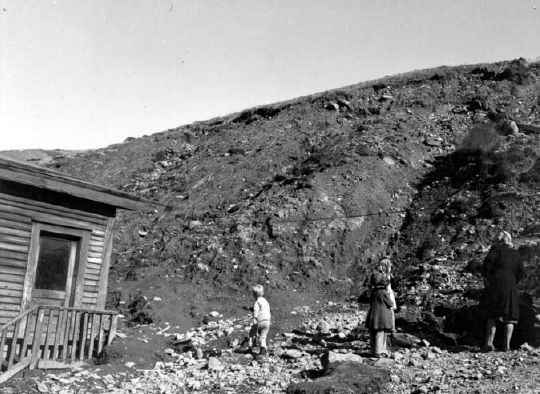

Luckily, there don’t seem to have been any berrypicking fatalities. There were, however, significant and sometimes deadly landslides along Southside Road in 1912, 1934, 1936 and 1948. I can’t help but wonder if this might have inspired the famed geologist (not the songwriter!) Hank Williams, who grew up on the Southside and went on to pioneer the concept of plate tectonics.

The scar left by the landslide of 15 September 1948 at 387 Southside Road (St. John’s City Archives)

The Second World War also left its mark on the Hills. Visitors to Fort Amherst have probably noticed the boarded-up entranceways along Southside Road. These lead to tunnels which were used to store explosives during the war (for a peek inside, visit Hidden Newfoundland). Military barracks and armaments were constructed on the hills, and “several houses were torn down to allow construction of improved docking facilities,” according to the Encyclopedia of Newfoundland and Labrador (1994). As a result, the population of the Southside began to decline. But Confederation brought even more drastic changes, as the Encyclopedia continues:

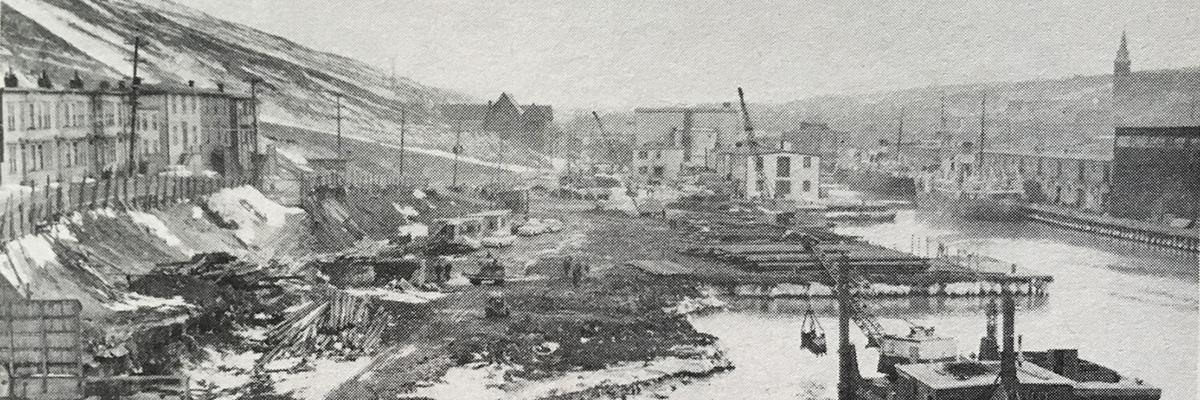

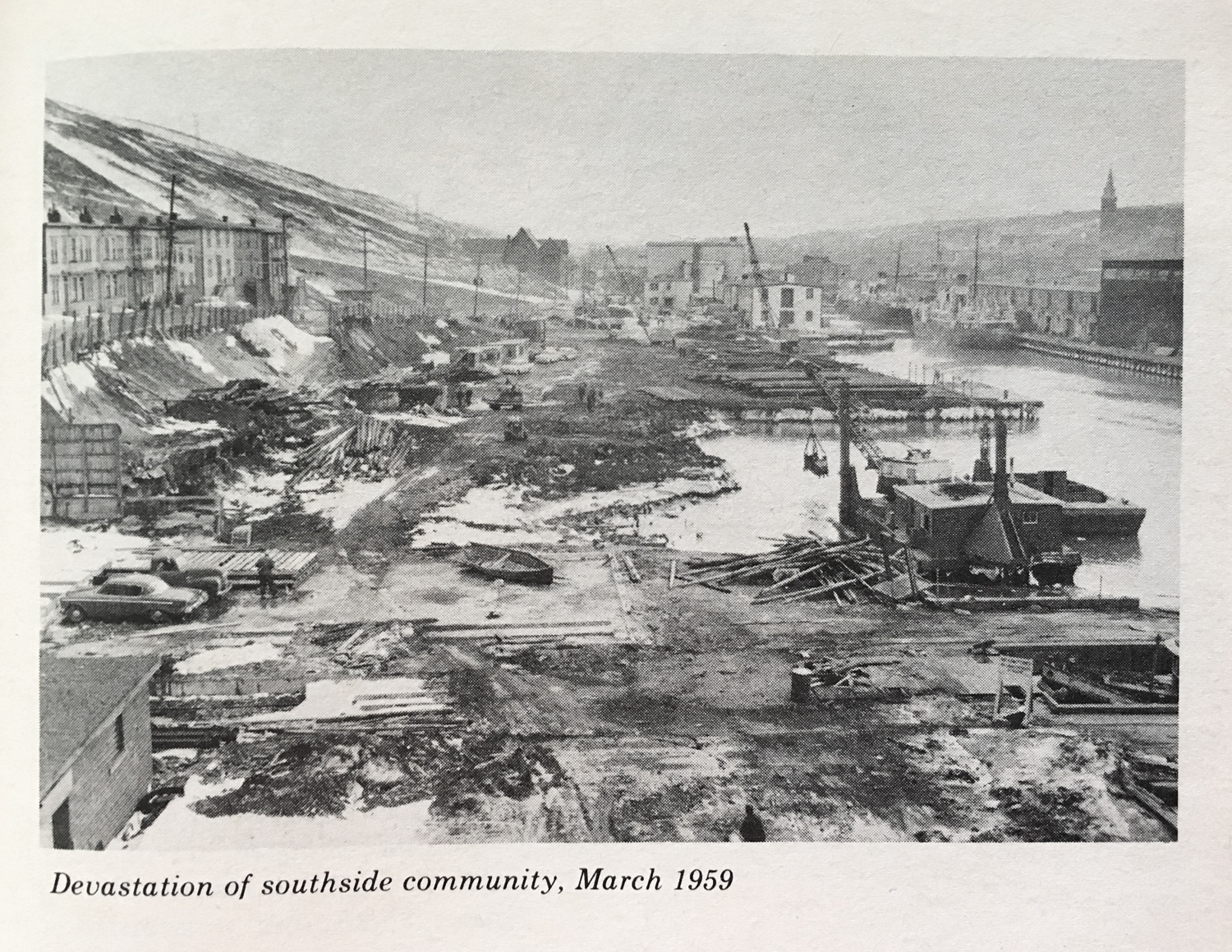

After Confederation, a major blow to the residential and historical Southside occurred when St. John’s was brought up to national harbour standards through a series of renovations. Between 1959 and 1964 many houses of Southside East were torn down and much of the Hill dynamited in order to widen the road. St. Mary’s Church was demolished, as was the grave of Shawnadithit, who had been buried in the Royal Navy’s Southside cemetery in 1829.

Devastation of southside community, March 1959, from Helen Fogwill Porter’s “Below The Bridge” (Breakwater, 1979)

The Southside shows up several times in the Dictionary of Newfoundland English. Under old, I found M.F. Howley again: “The ‘Old Man’s Beard’ is a patch of snow on the ‘Southside Hill,’ which from its position in a deep ravine is protected from the sun’s rays, and remains long after all the other ice and snow have disappeared and the trees have put on their summer’s verdure.” And, more ominously, under goat: “Billy goat, nanny goat: nicknames for people born on the Southside, St John’s.”

Writer David Benson addresses the stigma of the Southside, and the ruination of his childhood home, in a powerful essay titled Goats:

Of the destruction of the Southside, she cannot know, probably thinks Harbour Drive has been there forever, cannot comprehend water lapping the pilings under Bowrings and the London and every building on that side of Water Street. Cannot believe a whole community was rubbed out for rock and to fill in between the wharves of Beck’s Cove, Ayre’s Cove, Baird’s Cove and the rest. Does she wonder why these short streets are called coves? […] I remember the bulldozers and the wrecking gangs and the people terrorized into selling out for a few months’ rent; walls torn down when those in an adjoining house finally quit the racket and moved to the north side.

Benson’s essay can be found in his book And We Were Sailors… (2002). The writer himself can often be found on Duckworth Street, where he’s operated Afterwords bookstore since 2005. Here’s a little more from Goats:

“Our house? It was at the bottom of Ford’s Hill. We had two front gardens, terraced, with steps running up the middle. You wouldn’t know a house was ever there, if you wouldn’t know. It’s all gone now, the hill is like someone took an axe to it. Most of our land is at the bottom of the harbour, on the north side, under Harbour Drive, maybe under the heritage railway car.”

Southside St. John’s, 1940s (from The Rooms Archives).

Perhaps the most well-known chronicler of the Southside is Helen Fogwill Porter, who received the Order of Canada just last year. Today, the footbridge connecting the west end of Water Street with the Southside is named after her. In Below the Bridge (1979), her memoir about growing up on the Southside in the 1930s and 40s, Porter writes poignantly of losing her sense of place:

South Side Road East, or my South Side, as I secretly think of it, was wiped out in the late 1950s to make way for a national harbour. The people who lived there were evicted in the name of progress. The road itself is still there, or a new, improved version of the road, much wider now, paved and mud-free. It would be easier to keep the houses clean than it used to be, if there were any left there. …

When I walk down the revitalized South Side Road now, I don’t know where I am. Yes, that is the literal truth of the matter, I just don’t know where I am. And I don’t think I should have used that word “revitalized.” It implies that new life has been put into the place, when the truth is that life has gone out of it. It’s smooth driving over there now, yes, and there’s not much danger of being splashed by cars and trucks plunging through the mud, but where is everything? It’s not simply that the houses have all disappeared — it’s as if they never were. Where was Aunt Viley’s house, Whitten’s Shop, Morey’s premises, the house I was born in, the stone house where we lived when Dippy caught the huge rat, the hen house that was transformed into a club-house? Where was Hickman’s big warehouse, the Hundred Steps, the New Range, the house where Mrs. Walt Harvey’s parrot shouted greetings from the veranda?

St. John’s from Southside Hills, 1940s (from The Rooms Archives).

Helen Fogwill Porter also wrote a song called South Side Hills, which has been recorded by Phyllis Morrissey. There’s another lovely song by Mary Barry called Southside Hills of Home (you can find it on iTunes):

Crossing the bridges to St. Mary’s Church,

they could see the old city just round the perch.

A-courtin’ on Sundays under dad’s watchful eye,

But now the whole town’s gone, replaced by a sky.

Man carrying planks on Southside Hills above St. John’s Dry Dock, 1939 (from The Rooms Archives)

Juxtaposed with Porter and Benson’s passionate, personal writing about the Southside, Percy Janes’s poem The South Side In Winter feels distant and disconnected, as if it could be about any snow-covered hill. From the 1989 anthology Banked Fires:

The long-backed beast now settles down for a protracted rest:

slowly he stretches forward sandstone paws, gathers his granite shoulders in

and lets the snow-furred pelt on winter bind him round for polar sleep;

in bowel depths his heart may still be pulsing warm, but all along

that yielded frame, from corrugated tail to haunch and flank

and saurian-curving bouldered neck, an icy stillness rules.

Before the final freeze the monster slides his crusted eyelids down

and then from stony ledge of lip, slow-pointing day by day,

he grows his giant walrus teeth, that hang and hold

useless and beautiful, enamel-hard; till at spring-softening needle ends

pale blood of winter starts to drip, announcing soon

that old leviathan will wake and yawn his arctic armor off again.

View of the Southside: houses and St. Mary’s Church with the harbour in the foreground (undated, from MUN DAI).

This literary hiking tour through the history of the Southside has turned out to be longer than I imagined. I’m sure there’s plenty I’ve missed along the way, and we haven’t even gotten started on the future. But for now let’s wind our way home with another verse from Bishop Howley’s Dear Old South-side Hill:

I’ve seen the hills that proudly stand

And stretch from shore to shore,

In many a bright and favored land

Far famed in song and lore,

But, oh! there’s none so dear as thou,

Old shaggy South side hill,

For thy iron front and beetling brow

My soul with rapture fill.

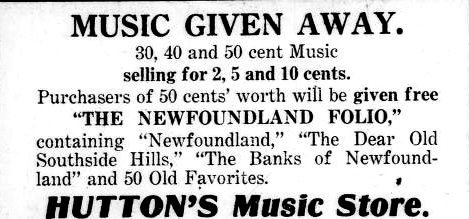

An Evening Telegram ad from 1914 hawking Howley’s song. As a songwriter, Archbishop Howley is perhaps better known today for writing the words to The Flag of Newfoundland.