The Grammarians War

March 2020

If I understand this correctly, The Grammarians War was a 16th-century, Tudor-era conflict (1519-1521) between rival methods of teaching Latin. The opposing sides were led, respectively, by schoolmasters William Horman (of Eton College) and William Lily (of St Paul’s School), and Robert Whittington, who taught in London in the 1510s. They attacked and counterattacked through a series of publications (pamphlets) and vindictive theatrical gestures like Whittington nailing his satirical verse to the doors of Old St Paul’s Cathedral. What was at stake in this quarrel?

The war waged between the defenders of prescriptive pedagogy, which emphasized rule-based learning and was associated with medieval forms of instruction, and the representatives of the ostensibly imitative methods promoted by humanists who encouraged the reading and critical analysis of classical texts. Moreover, the participants in the Grammarians’ War offered pedagogical as well as literary models for future educators, and their poetic anthologies printed in relation to this fictional battle considerably enhanced their self-representation and reputation as Neo-Latin poets. The controversy, however, was not restricted to issues of grammar, pedagogy, and literary self-fashioning, but was also motivated by the ongoing struggle to secure position and patronage for these socially well-connected schoolmasters at the Tudor court. After this public intellectual debate, Lily and Whittington in particular were rewarded with prestigious commissions from the royal court.

How was their choice of typography significant?

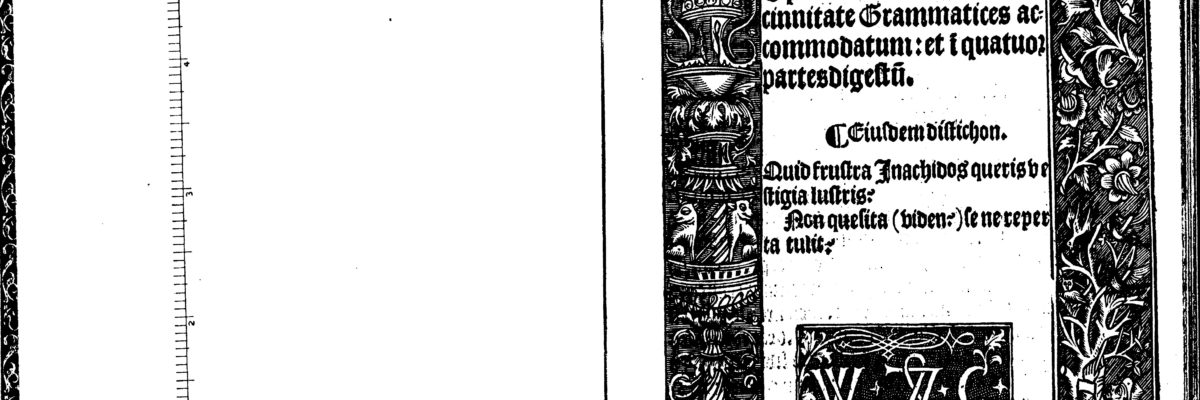

In their respective pamphlets, both Lily and Horman isolate typographically Whittington’s poems through the use of black letter or Gothic type, which was associated with medieval manuscripts. The Gothic type suggests that Whittington is a representative of a by-gone era and that he does not share their humanist mindset, a mindset that was visually expressed through Roman type in contemporary print publications. Interestingly, during the Grammarians’ War, the typography of Whittington’s textbooks and even his poetic response to Lily and Horman were updated and, as the attached title pages illustrate, the black letters was replaced with Roman type to make him look more progressive which also made him more marketable.

I liked this comment you made: “I try to focus on the literary but you can never separate it from the political.” Can you expand a little on that?

Through these hotly debated humanist educational methods, students acquired important practical skills in rhetorical strategies, which formed the basis of a variety of early modern discourses, including literary, philosophical, legal, religious, and political writings. Moreover, the techniques of language instruction entailed not only the inculcation of grammatical rules, but also the internalization of a set of moral values (derived from classical moral philosophy), which equipped students to become effective political and religious leaders and counsellors of rulers. This complex set of skills was indispensable for political advancement and courtly preferment. In fact, when we consider the disciples of these schoolmasters, we find among them many members of the governing classes and leading intellectuals of the early Tudor period. Emulating other Renaissance courts in Europe, the Tudors prided themselves on creating opportunities for social mobility based on intellectual merit rather than merely noble birth. A thorough humanist education was therefore a valuable asset for a broadening class of people throughout 16th-century England.

Do you secretly sympathize with one side over the other?

Since I am currently working on a critical edition of Lily’s poetical works and, for a number of years, I have focused on the scholarly and literary activities of schoolmasters who were, in one way or another, related to the Lily-Horman circle or studied at their schools, I am more familiar with their side of the story and perhaps inevitably more sympathetic or biased towards them. But as a result of my recent research on the Grammarians’ War, I became quite intrigued by the figure of Whittington, who was generally regarded less favourably by later generations of scholars. I hope to explore in more detail his perspective on this peculiar battle, which eventually led him to abandon publishing grammatical handbooks and to reinvent himself as a popular English translator of classical Latin works.

Ágnes Juhász-Ormsby is Associate Professor with MUN’s Department of English, with a special interest in Early Modern Studies.