Textiles, tap shoes, and heirloom tomatoes: street tiles & high fashion of a California city

March 2025

BY EVELYN C WHITE

The life expectancy for Black women born in the US (such as myself) is 76.1 years compared to 80.5 for our white counterparts. Now age 70, I’m not long from my projected “use by” date.

Hence, barring dramatic shifts in the American political landscape over the next three election cycles (ie 12 years), it’s not likely that I — who’d then be age 82 —will witness a woman of African ancestry claim the highest position in the land.

I’d hoped to participate in the Kamala Harris inauguration festivities when I planned, last October, a lengthy retreat from my Halifax home to Berkeley, California, where the former vice president had once lived as a child. Nope.

Still, I’ve been cheered by the many Harris campaign signs that remain visible throughout the city despite her dispiriting loss. I’ve also kept my “sunny-side up” by boosting my supply of tie-dye in a locale where the attire is plentiful and the counterculture still holds sway.

Indeed, “The Berkeley Tie-Dye,” a sweet, heirloom tomato with swirling red and yellow stripes is a top seller at the city’s year-round farmers’ markets.

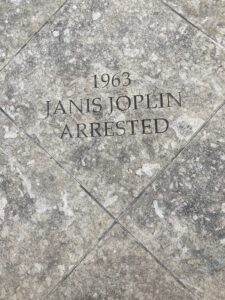

As for those gleaming commemorative plaques that honour notable people or places in municipalities from St John’s to San Diego? Visitors to downtown Berkeley will instead find a beloved street tile that marks the spot where singer Janis Joplin was arrested (cue: “Get It While You Can”) for shoplifting, at age 20.

On a nearby corner, in a continuation of the musical theme, stands “Earth Song for Berkeley,” a red steel tuning fork measuring 13.7 metres tall. Crafted by local artist Po Shu Wang and installed in 2002, the vibrating sculpture is reportedly the largest tuning fork in the world.

It’s a fitting symbol for the city that embraced the 1960s era “Turn on, Tune In, Drop Out” philosophy espoused by University of California at Berkeley graduate (and psychedelic drug guru) Timothy Leary.

Set to instantly recognizable music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (i.e.“The Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy”), The Nutcracker ballet traces its roots to works by writers Alexandre Dumas and ETA Hoffman. It premiered in Russia just before Christmas in 1892 and has since been mounted by classical ballet companies around the world during the holiday season.

But in Berkeley, the December 2024 performances of The Nutcracker were presented by Dorrance Dance, a New York-based ensemble that took to the stage in tap shoes instead of ballet slippers. I was among the multitudes in the audience who marveled at the talents of the multi-racial troupe as they time-stepped and cramp-rolled to a vocalist backed by a live jazz combo.

A program note read: “A rhythmaturgical evocation of the … enchantments of Duke [Ellington’s] … supreme adaptation of Tchaikovsky’s masterpiece.”

In addition to traditional hoofers in revamped Nutcracker roles such as “Sugar Rum Cherry,” the show featured break dancers busting moves in tap shoes. The crowd went “Berserkeley,” as the saying goes.

In a counter to the city’s madcap reputation, Berkeley is also home to the Lacis Museum of Lace and Textiles. The “old world” depository of countless specimens of lace was founded by Kaethe Kliot (1930-2022), a native of Germany who became proficient in the needle arts as a child.

After suffering the death of family members during the Second World War, Kliot made lace doilies that she sold to American soldiers. She later used earnings from her handiwork to emigrate to Windsor, Ontario, where she met her future husband. The couple moved to Berkeley in the mid-1950s and, in 1964, opened the emporium that celebrates the history of lace from the prized French Chantilly to factory-made pieces for “everyday use.”

I visited the museum with a friend whose late mother, Caroline, had worked as a pattern editor for a major needle crafts company. The elegant woman was also skilled at tatting, crochet, quilting, knitting, and embroidery. “She would have loved this place,” my friend said.

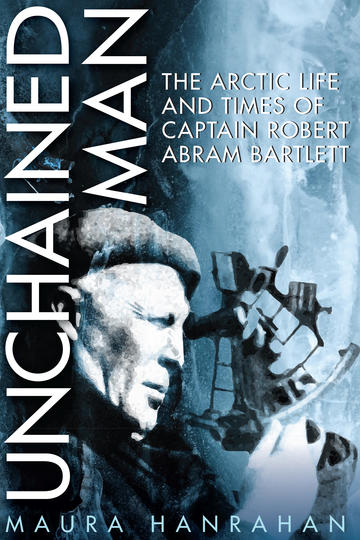

My sojourn at the Lacis Museum was fresh in my mind when I later noticed a coffee table book on display at the Berkeley Public Library. The volume? Ann Lowe: American Couturier, the catalogue from a 2023 Delaware museum exhibition of the same title.

The absorbing collection of essays chronicles the life of a Black woman born impoverished in rural Alabama who dropped out of school at age 14. But undaunted and inspired by several gifted seamstresses in her family (including an enslaved great-grandmother), she forged a career as a trailblazing fashion designer who was later dubbed “Society’s Best-Kept Secret.”

Why the sobriquet? Among other achievements, Ann Lowe (1898-1981) designed (and painstakingly hand-stitched) the ivory silk taffeta dress that Jacqueline Lee Bouvier wore when, in 1953, she married future US President John Fitzgerald Kennedy. However, Lowe’s part in “Camelot” — a reference to the hit 1960 Broadway musical — that epitomized the hopes of the ultimately, ill-fated Kennedy administration, was not immediately publicized.

Why not? Reportedly because of her race.

African-American scholar Margaret Powell (1975-2019) was the first to research the couturier’s life and art. Writing in Ann Lowe, she noted: “The New York Times covered society’s wedding of the year on its front page. … For the dress designer, this type of international exposure should have represented a turning point in her career. Detailed photographs of the gown … should have brought priceless name recognition and waves of profitable business opportunities …Yet in all of the coverage … the designer … was not identified.”

Powell continued: “Even today, as the Kennedy wedding gown resides in the permanent collection of the John F Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston … very few people realize that this dress is the work of an African American dressmaker and that it is just one example of the countless dresses she designed for members of the Social Register, an elite segment of the American upper class.”

In addition to a riveting account of Lowe’s completion, twice, of Bouvier’s wedding dress (and that of her bridesmaids), the book is resplendent with images of the designer’s other custom garments. Among them: the aqua tulle, hand-painted floral gown that Olivia de Havilland wore when she accepted the Best Actress Academy Award for her role in the film To Each His Own (1946).

Delighted by my discovery of Ann Lowe: American Couturier and online videos about her career (especially a 1964 television interview with tantalizing reveals), my disappointment over the failed presidential bid of Kamala Harris lost some of its bite.

And I’m mindful that Harris, born of immigrant parents to the US, will forever stand as the first woman to serve as vice president of the country.

Hence, in celebration of International Women’s Day 2025 and the landmark accomplishments of both women, I made my way to a popular Berkeley alehouse to savour a pint. The brew? Midnight Silk Black Lager.

Booyah!

(Images: Lowe’s acclaimed dresses courtesy the Smithsonian; all others from Evelyn White)