One Point, Two Points, Three Points Mi’kmaq

May 2017

THE SAME WEEK I received a rejection letter from Indigenous and Northern Affairs declaring I was no longer recognized as Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation, my back gave out.

My body’s entire support system collapsed and I was bedridden for days. Keeled over, physically capsized, I prayed to Creator for rest, and made offerings to the ancestors for healing.

According to the papers, I am only three points Indigenous. Registered government documents determine whether or not I officially belong to a band and can lay claim to a nation. I needed thirteen points in total to keep my status. I’ve officially been on the books as a landless Mi’kmaq for six years.

The Enrolment Committee’s criteria includes, but isn’t exclusive to, visits to members of a location of the Mi’kmaq Group of Indians of Newfoundland (2 points), frequent communications (0 points), residency on the Island of Newfoundland (0 points), membership to Federation of Newfoundland Indians prior to June 2008 (0 points), and maintenance of Mi’kmaq culture and way of life (1 point).

George River’s caribou herd moves towards the point of no return. Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation are turning away members, and the caribou is near extinction. In this shambolic state, an erasure of identity and colonial drain, I can’t even stand upright, but I am worried about the herd. Caribou are noble and dignified creatures, essential to the landscape of western Newfoundland, my ancestral lands.

In Mi’kmaw, Qalipu translates to caribou, and we’re in an uproar because the government doesn’t recognize us anymore. Every single painful movement is five hundred years of genocide shooting through my back. I can hear my ancestors weeping in my spine.

Our families are in fragments, relationships strain under the weight of shame, pathways are being lost. Roots systems are tangled up in colonial drama. Some of my cousins ranked zero points Indigenous, yet their children kept their status cards. Aunties had fewer points than me, yet father ranked only half, almost Indigenous.

In the era of Truth and Reconciliation, and the throws of Canada’s horrifying 150 year celebrations, our collective histories are being forgotten. The Canadian government doesn’t believe Newfoundland could have one of the largest Indigenous bands in the country. Joey Smallwood confirmed upon 1949’s Confederation, there were no Indians on the Island of Newfoundland, so today, Trudeau doesn’t believe I’m Indigenous enough. Neither are thousands of Mi’kmaq people.

You took our land, our language, our sacred rites, our crafts, our spiritual practices, and now you are taking back our status cards? You’ve already robbed us of our dignity, our synergy. George River’s caribou herd are dying out, and we, former Qalipu members, are being killed off a letter at a time.

Father drops by with medicines and news, something to help heal my back. He has called Chief, and we must gather strength, and recover in numbers, submit our papers for appeal.

I’ll never forget when father first showed me his status card. It took a plastic card with ten digits, a black and white mugshot photo, and a tiny Canadian flag in the corner for him to truly see himself — to recognize and honour our ancestors.

At 66 years old and six points Indigenous, father is having his card revoked. At 33 years old and three points Indigenous, I’m losing mine too. Trudeau, I can tell you, my Mi’kmaq culture means more to me than a registration number. You can keep your digits.

All my relations,

Formerly, Registration Number : 0341945201

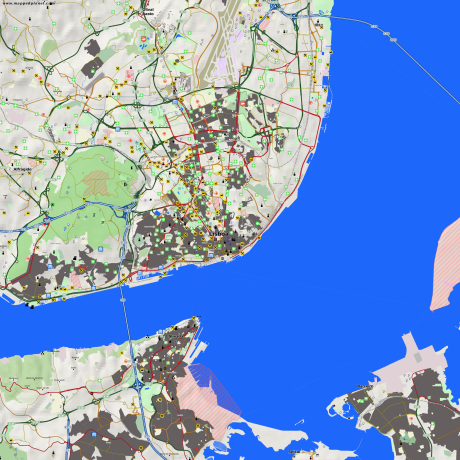

![[re]claim: magtogoeg / humber river](http://nqonline.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/MeaganMusseau-MAGTOGOEG-2017-1024x751.jpg)

[re]claim: magtogoeg / humber river: place name documented by the French while guided by the Mi’kmaq in Ktaqamkuk / Terre-Neuve / Newfoundland copyright 2017 Meagan Musseau