No place for women: Hilda Dove in the Arctic

August 2018

In 1930, a Newfoundland woman celebrated her 20th birthday in Greenland. Her smile was wide as she posed for the camera. She was on board a ship skippered by Robert Abram Bartlett, who was world-famous as a result of his Arctic heroics.

Few environments were as masculine as Bartlett’s harsh forbidding Arctic. Here, men caught seals with their bare hands and sheltered, shivering, in tents ripped apart by relentless winds, their bellies half empty. As Margaret Atwood once wrote, “even though the North itself, or herself, is a cold and savage female, the drama enacted in it…is a man’s drama, and those who play it out are men.” These men were white, drawn from the elite of Britain, the United States, Canada, and Norway as well as other western countries. (Matt Henson, the African-American who made the final trek toward the North Pole with Peary, was an exception.) As they wrote of their adventures, they backgrounded the Inuit men and women whose hunting and sewing skills were crucial to their survival.

These men came from Newfoundland, too, with members of Bob’s family playing central roles in the history of Arctic exploration. Captain John Bartlett, Bob’s uncle and likely Newfoundland’s first qualified master mariner, brought the Isaac Israel Hayes expedition to Melville Bay in the Bartletts’ vessel, the Panther. His brother, Captain Sam Bartlett, skippered the Neptune in 1903–4, a voyage that culminated in Ellesmere Island being claimed by King Edward VII and the establishment of Canadian law and customs in the Eastern Arctic (with lasting consequences for the Inuit).

A few white women travelled to the Arctic; among their small number was Josephine Diebitsch-Peary who arrived in Greenland in her capacity as Admiral Robert Peary’s wife. Women were not welcome on the voyage. One noteworthy female explorer was the Californian Louise Arner Boyd, who went north with Bartlett during World War II. Boyd was loathed by Bartlett who held the view, typical for Newfoundland at the time, that women did not belong on board ships.

Bob made an exception for his niece, Hilda Bartlett Dove, who had grown up in St. John’s, spending many summers in Brigus at Hawthorne Cottage with her grandparents, Mary and Captain William. Hilda was the daughter of Bartlett’s sister, Beatrice Stentaford Bartlett Dove, born in 1876, a year after Bob, and known as Triss. Triss married Wilfred Dove of Twillingate and named her daughter after her own sister, Hilda Northway Bartlett, who had died in childbirth at age 26, taking her newborn with her.

Hilda’s mother, Triss.

Family loyalty was prized by the Bartletts and was one of the keys to their financial and reputational success. Bob often took his relatives on his trips north, especially after he acquired the Effie Morrissey. Among those who travelled with him were his brother, William, a Brigus farmer, his young cousin Sam Bartlett, and his nephews Jack Angel, Robert Dove, and Jim Dove.

Bob took 20 year old Hilda to Greenland at least once. In 1930, Hilda was pictured in the New York Times, which often reported on Bartlett’s voyages, in full Greenlandic Inuit dress on board the Morrissey. Thus, in violation of the age-old gendered code to which he enthusiastically subscribed, Bartlett had allowed a woman on his ship. This change of heart could have come only via Hilda for she and her uncle were extremely close and shared the same wanderlust.

No one would have accused Hilda of being ordinary. Unmarried at 28, she made a lengthy solo voyage from Newfoundland to the English countryside, then on to Lisbon, the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa, and then west again to South America where she journeyed to Rio de Janeiro, Montevideo in Uruguay, and, in her own words, “the great city” of Buenos Aires. “I have had one hell of a fine trip since leaving Newfoundland,” she wrote jauntily to Bob, “That does not sound very ladylike but you will admit it is descriptive—and to relate it in detail would fill a volume the size of Gone with the Wind.” Hilda relished the three-week crossing of the South Atlantic as “the abundance of sea air [was] better than any tonic.” In spite of the high temperatures in South America, reaching 107F, she was “A1.”

Hilda shared Bob’s curiosity and his talent for observation. She was fascinated by life in the foothills of the Andes, writing that “the agriculture and produce of the very fertile land, the cattle ranches, the mining of limestone, the growing of the sugar cane, and the manufacturing, the numerous species of birds, insects, animals, flowers and trees, the people themselves and their very primitive modes of living are all so very interesting and provide ample food for thought.”

Hilda was a graduate of the Methodist College in St. John’s, where Lady Middleton, fresh from London, attended basketball games and Lady Crosbie, who had married into the Crosbie family of Brigus, presented the trophies. Academic, athletic, and confident, Hilda would not have been intimidated by the college boys from New England who paid to act as sailors on the Morrissey, thus partly funding Bob’s trips.

It is not a stretch to imagine Hilda at Bob’s side as an explorer had she not been born female. But, as Ernest Shackleton once made clear in a curt response to women applicants, roles in polar exploration were the purview of men. That Hilda Bartlett Dove got herself to Greenland via the Morrissey speaks not only to her obvious family connections but also to her determined and adventurous spirit. To his credit and in spite of the hyper-masculine culture in which he lived and which he cultivated, Bob recognized and nurtured this spirit.

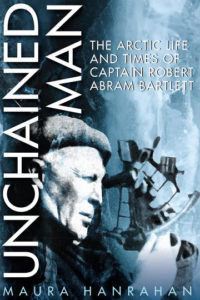

Maura Hanrahan’s new book, Unchained Man: the Arctic Life and Times of Captain Robert Abram Bartlett explores the life and complex character of the explorer. You can find more at her blog or by following her on facebook.

While you’re here:

… we hope you enjoy our website! Our online audience is growing every month, and that means that more people like you are seeing and reading incredible new work by Newfoundland and Labrador writers and artists. We want the people of the province to have access to high quality, contemporary writing about the unique and ever-evolving culture of this place, so we’re offering our online content for free. That said, if you’re able to help us keep providing this opportunity to both readers and creators in Newfoundland and Labrador, we encourage you to subscribe to our print magazine. Subscription details are here. If you ‘d like to support us with a donation or legacy gift (tax receipts available,) please contact us at rcohoe@mun.ca.