More Folly than Sense

BY Sharon Bala

January 2018

When I finished writing The Boat People, there was so much left behind on the cutting room floor – scenes and chapters, entire characters and storylines – that I sometimes joke it could fill a whole other book. It can be hard, as a writer, to take scissors to your work but I try to remind myself that nothing is a waste. All those passages that got deleted represent crucial quality time I spent with my characters.

The scene below is a standalone flashback that takes place in Sri Lanka 22 years before the novel begins. The main character, Mahindan, is a young boy, a lifetime away from becoming the widowed father who appears in The Boat People. Writing this anecdote from Mahindan’s past made me realize something important about his personality and I always thought that if readers had access to it, they would have a hint to solve a mystery that exists at the novel’s centre.

The scene below is a standalone flashback that takes place in Sri Lanka 22 years before the novel begins. The main character, Mahindan, is a young boy, a lifetime away from becoming the widowed father who appears in The Boat People. Writing this anecdote from Mahindan’s past made me realize something important about his personality and I always thought that if readers had access to it, they would have a hint to solve a mystery that exists at the novel’s centre.

They had taken a camping trip once, Mahindan and his cousin brothers, Shangam and Rama, with their tents and their bicycles, unchaperoned for four days. They travelled mainly on their own steam but hitched rides when they could, jolting over potholes in the wagon of a farmer’s tractor, the hot sun baking the tops of their heads.

They were on their best behaviour for these good Samaritans. Please, Sir. Thank you, Sir. And on their worst on their cycles – catcalling girls and throwing stones at the skinny brown cows that plodded dumbly along the roadside. They whizzed past old men tottering on canes – zipping by, one after another, so close their slip stream ruffled grey hair. Thirteen years old and full to the brim with more folly than sense.

On the last evening they ran short of money. Closing in on the beach, they stopped for rations in a village. It was a prosperous-looking place, full of familiar, comfortable sounds. Wood splitting under an axe blade, onions hissing in a frying pan, the rumble of a returning motorcycle, the creak of a swing – the gentle winding down of evening.

They peddled past whitewashed bungalows set in generous gardens. The roofs were tiled with orange terra-cotta. Palmyra trees wafted in a salty ocean breeze.

These buggers live well, Shangam said.

Rama sniffed the air. Do you get the smell of fried egg?

Not this again, Shangam said.

There’s a kade, Mahindan said.

The small shop was a timber-framed hut with rudimentary clay brick walls. The roof was a sheet of corrugated metal that jutted out several inches past the doorway, shading the inventory displayed on two wooden tiers outside.

Combs of plantains, still bunched on the branch, hung down from the rafters and underneath, pyramids of hairy shelled coconuts and green papayas. There was a basket overflowing with grapes, a round tray of mangosteens, and, on the ground, burlap sacks of rice. Plastic bottles, lukewarm to the touch, were displayed under a sign that read “cool drinks” – water on the bottom, Coca-Cola and Fanta at eye-level.

All the best things – the biscuits and cigarettes – were kept on a window sill, behind which the shopkeeper conducted transactions. He had a squat bulbous nose and a grey-flecked moustache and was serving a customer when they arrived, a woman with a sack of rice at her feet. He eyed them, suspicious.

A small girl in a frilly mint green dress stood barefoot in the doorway of the hut. Mahindan saw an untidy collection of overturned cardboard boxes in the shadowy interior behind her. The girl had a plastic clip, blue and in the shape of a butterfly, affixed to her bowl cut. There were gold studs in her ears.

They idled for a few minutes, while the woman at the counter asked about the carrots. These are a little small, no? she said. Can you not give a better price?

Half a dozen chickens clucked, pecking at the ground around their feet. Mahindan squeezed a papaya. Shangam fingered a grape, then glancing swiftly at the shopkeeper, twisted a cluster off and slipped them into his pocket while examining the mangosteens.

Rama picked up a bottle of Fanta and Shangam slapped his hand. We don’t have money for that. Get the sex bananas, he said with a leering, knowing look, and reached up to break off three of the stout red-skinned variety.

The little girl poked her toe at the ground, brushing at the tufts of grass growing out from between the cobblestones. Mahindan grinned at her and scratched the back of his head.

A stray dog barked from across the street, startling the hens. They rushed off, pushing past each other with throaty clucks and flapping feathers, wide backsides waggling like silly gossips. Mahindan and Rama leaned around the corner and watched them disappear into the garden of a house behind the shop.

Those are our chickens, the little girl said.

They chose six bananas, a litre of water and three papayas. At the counter, Shangam added a packet of biscuits to the pile.

Have you any eggs? Rama asked.

The shopkeeper reached under the window and brought out a half carton. Six perfect eggs, white and brown with freckled matte shells, sat nestled in their cardboard cups.

Shangam laid their money on the counter and the shopkeeper counted out the coins, flicking each one with an index finger into his upturned palm. They were short three rupees. Rama pointed out it was the end of the day.

Can sell tomorrow, the man said. He picked up a ruler in one hand and slapped it against the other, repetitively like a strict head master.

There was a flurry of feathers and noise as the chickens returned, rounding the corner, five falling on a sixth, pecking and clucking, their beaks attacking the victim’s head. The little girl ran at them, waving her hands. Go! Go! she yelled scattering the assailants.

But you’ll have new eggs tomorrow, Rama whined.

The man snatched the carton away. Get out! he barked. Before I take this ruler to your backsides.

They shot off on their cycles, spraying up dust and flashing rude hand gestures in their wake.

*

Rama wouldn’t shut up about the eggs.

Full-boiled, he said, longingly as they pitched the tent on the beach. A nice egg hopper with a bit of –

Shut up will you-men! Shangam threw a fistful of sand at his head and Rama ducked.

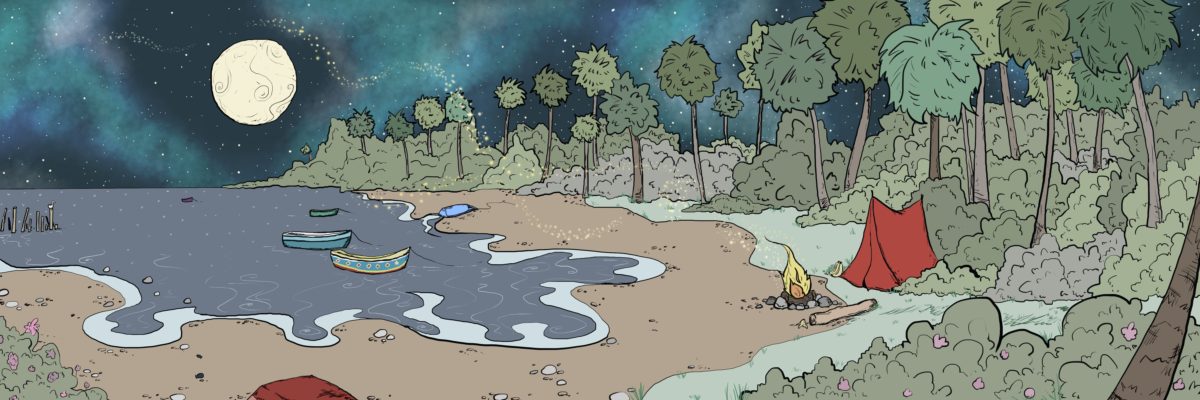

They changed into long pants and made a small fire as the sun disappeared and the sky flamed orange and red. The surf swallowed the shore before receding away, white and foamy. The beach was quiet, golden sand dotted with detritus – gnarled logs of driftwood and, closer to surf, a scattering of broken shells.

A woman pushed a bicycle along the shore. A couple flirted under the low hanging fronds of a palmyra tree. The boy leaned back with one foot on the trunk and spread his hands apart, palms turned up. The girl brought her braid over a shoulder, pulling at the end.

Mahindan finished his banana and wound his arm back over his head to toss away the peel. He dug in with his feet, feeling the sand grit up between his toes.

He and Shangam were engaged in a serious discussion they’d been conducting on and off all day. Shangam jumped up and posed, bent over an imaginary cricket bat. And then I would hit in over the boundary, he said. Six runs!

Egg scramble, Rama said. An omelet. With a bit of chili flakes on top.

It’s always food with this one, Shangam said.

Mahindan leaned over and pinched at the roll straddled around Rama’s midsection. As if you need another egg in there.

Rama crossed his arms mutinous. I’m hungry.

How has your Amma not drowned you yet? Shangam flopped down. He pulled the grapes out from his pocket and gave them to Rama.

The sky was dimming, the stars beginning to shine. Blue and yellow fishing boats bobbed offshore, nets cast out behind, their owners hoping for bountiful overnight catches. Crabs, cuttlefish and stingrays that would be hauled in at dawn. Gutted and salted, then spread out to dry in the sun, the whole beach ripe with the stink by noon.

Only three rupees short, Rama mumbled, his mouth full of grapes.

He looked a real mudalali, Shangam agreed. Miserly fellow.

Mahindan remembered the hens, the little girl with the party dress. Okay, okay, he said, using the English expression. Just keep quiet and tomorrow, I’ll get you an egg.

*

They left early the next morning, as the fishermen were heading out in their boats. The world was still dark when they strapped on their headlamps and cycled back to the village. Mahindan stood on the pedals, torso leaning forward over the handlebars, aerodynamic. The pre-dawn chill goose-fleshed his skin.

The village was different at night – shuttered and vulnerable. Dogs slept in doorways. The little shop was closed up, a board covering the window, a fat padlock on the door. The shelves sat naked, ropes hanging down from the rafters, bananas gone.

Stashing the bicycles in the bushes and switching off their headlamps, they approached on foot. The moon watched, conspiratorial.

They slipped through the front gate and took slow, careful steps toward the house, eyes still adjusting to the dark. Gradually, shapes began to clarify out of the shadows. A pile of coconut husks. An oleander bush. A chicken coop.

There, Mahindan whispered, and they made a beeline.

Something white shone between the bars of a back window, catching his attention. Mahindan glanced over and saw a glass bottle. The tapered neck, the perfect O of its mouth.

He made a sharp turn and the other two followed. The quart of milk sat on the window sill, tantalizing behind the iron bars. An unexpected boon.

He sidled up to the house and stood on tiptoe against the wall, craning his neck to look inside, but the window was too high.

Shangam and Rama were close at his sides. He could feel their excitement, the quick, shallow bursts of air they exhaled through slightly open mouths.

Stay back, he muttered.

Reaching up, he slipped a hand between the bars. The glass was cool. He grasped the bottle at its centre and lifted it carefully, straining to hear a sound from the house. The trees and the flowering bushes, all the foliage stood still, holding a collective breath.

Even before he eased his wrist out he knew, the bottle was too wide. It would not fit through the bars.

Rama groaned in frustration and Shangam shushed him. There was a rustle in the grass, a garden snake or a mouse.

Mahindan felt the yawning hollow of his stomach. He thought of the shopkeeper slapping the ruler against the flat of his palm. The bottle of milk was in Mahindan’s hand. He laid it down on its side, working with both arms high above his head. He eased the mouth and neck between the bars so that half the bottle stuck out the window.

Shangam and Rama tittered behind him, elbowing each other in the stomach and covering their hands over their mouths to muffle their mirth.

Mahindan positioned himself, torquing his body awkwardly until his mouth was directly under the bottle. Moonlight bounced off the milk. He peeled away the aluminum foil and held his mouth wide open. Milk poured in, lukewarm and sweet. He took quick gulps, liquid dribbling over his chin and down his neck.

Shangam poked at him and Mahindan stepped aside, wiping at his mouth and neck with the hem of his shirt. The stars were dimming, the sky swiftly turning from black to blue. He had not forgotten the eggs.

The chicken coop was a wooden construction lifted two inches off the ground with a peaked roof. The door frame was filled in with wire netting. It creaked when Mahindan eased it open.

The coop was warm, fat hens slumbering, their brown feathers rustling. Light shafted in through the netting on the door. It smelled faintly of ammonia.

Mahindan crouched in the straw and considered his options. He had found a thin stick in the garden and had it clutched in one hand. He counted six hens. No cock.

Carefully, he slid the stick under a hen, lifting away a wing and feeling with a blind hand, through the warm straw and feathers. The hen stirred in her sleep, then turning her head seemed to wake, blinking at him with a questioning, throaty gurgle. He remembered that chickens were blind in low light but his heart beat a little quicker and he gripped his stick. His hand closed around an egg and he scooped it into his pocket. The chicken lowered her head.

He worked his way around the coop, unhurried but efficient, anticipating the awe that would greet him when he returned with his purloined bounty. They had brought a little saucepan and could find a nice corner to cook a good breakfast. A feast of fried eggs, sunny yolks turned up, crisped, gathered edges.

He moved on his haunches, straw crunching underfoot. The hens gurgled, contented, in their sleep. They were prolific – two, sometimes three eggs in a nest. They bulged out his pockets. He turned up the bottom of his shirt, making a little basket to carry away more, then clambered out of the coop awkwardly.

Outside, the day was coming to life, the sky a mellow hue. Rama and Shangam were nowhere to be seen. Mahindan strutted out of the garden, feeling pleased with himself. In the bowl of his shirt the eggs formed a generous cache. Their shells clicked together, bits of feather and chicken shit crusted on a couple. He thought of all the ways he could exaggerate this story when he got home.

Rounding the house, he saw his cousins had left the gate unlatched. The fools. They must have gone back to the bicycles. Just wait until they saw his haul. He’d be the hero of the trip.

Mahindan noticed the shopkeeper at the same moment the man saw him. He stood on the door step in a sarong and white sleeveless undershirt, scratching his belly and yawning. Mahindan and the shopkeeper both startled when their eyes met. The man yelled and Mahindan bolted, still holding his shirt up.

You little devil, the shopkeeper bellowed.

Mahindan ran hard, down the length of the garden and out the open gate, eggs rattling in a panic. He saw the bush where the cycles were hidden but there was no time. If he stopped to pull up the handlebars, the man would … and anyway, the eggs …

He glanced over his shoulder. The man was coming at him, eyes bulged out, a single threatening slipper in hand. Mahindan hurtled forward, past the shop, past trees and storefronts, and people emerging out of houses to see the commotion. Shangam and Rama in hiding somewhere, clutching their stomachs, paralyzed by the hilarity. A stitch tightened painfully in his side. He leapt over a rock. An egg rolled free and landed splat on the ground.

Behind him, the man howled in a rage. Wait till I catch you. I’ll give you a hammering!

Mahindan’s heart was in his stomach. His pulse was in his ears. Eggs tumbled out both sides of his shirt, leaving a trail of broken shell and oozing yolk.

Little thief! the man yelled. I’ll give you properly!

Mahindan let go of his shirt and ran unencumbered, legs and arms pumping hard. The eggs in his pockets jostled. He felt yolk seeping, sticky against his leg. Somewhere nearby, a rooster crowed, mocking from a rooftop.

The Boat People is Sharon Bala’s first novel, and will be published by McClelland and Stewart on January 2nd, 2018.