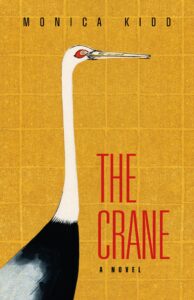

“It’s true that a lot of my day job involves hearing about trauma”: Monica Kidd’s The Crane takes flight

February 2025

I’ve always been fascinated by doctors who write – Chekov, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – at first glance it seems an odd match of skills, but what am I missing? That each requires a talent for observation, for example?

Observation is probably part of it, but I also think it has to do with the daily immersion in other people’s stories. A handy mnemonic for clinical encounters is SOAP: Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan. You start by hearing a patient’s experiences and thoughts, then you gather your own information from physical exam, investigations, etc. The diagnosis and plan come from balancing what someone else thinks, feels, believes, with what you think, feel, believe. In that sense it’s a kind of conversation. Allan Peterkin, a psychiatrist and writer in Toronto, likes to call medicine a narrative act. Maybe it’s also why many journalists become authors: even when trading in story is your day job, there will always be bits of stories that stick with you and interdigitate with your own life and imagination.

The Crane is deeply concerned with war(s) and trauma – is that focus coming from your medical background?

Maybe so, in ways that aren’t totally apparent to me. I’ve just always hated seeing people hurt. There’s probably an upstream reason that I went into medicine and am also concerned with war and trauma, something to do with wanting to make things less painful for others. (A therapist would probably go to town on that.) But it’s true that a lot of my day job involves hearing about trauma. Maybe if I can’t always ease someone’s real-life trauma, I can reach for some kind of healing in story.

The Vietnam War is the principle, but not only, conflict that backdrops the story. Why that time period? (And I liked how ‘timeless’ the first few pages were, to me; as James was coming into the train station, the reader was getting ‘clues’ to when this was taking place.)

Thanks! I think I borrowed that device from film, with an ambiguous establishing scene.

The Vietnam war has always haunted me. I was born in 1972, as the war was ending. Rightly or wrongly, the 1970s of my recollection (fabrication?) was time of ennui, with the continent-wide spectre of a “lost” war with its traumatized veterans, full of anger and prog rock, when it seems we stopped believing in the trustworthiness of institutions. My own early childhood involved a lot of secrets, and I think I must have had some spiritual overlap between trying to sort out what my own story was with the angry secrets of the adult world. I wanted to look at truth and lies, how lying can be done to manipulate and obfuscate, but also sometimes to spare people from the truth. I needed to examine my own assumptions about the war, any war. (I’m that annoying parent who would never let their kids play with guns.) I couldn’t write about the Vietnamese experience—it’s not my story to tell, but I had some kind of story that was mine that needed telling. The story of being a deeply affected, bewildered bystander. I wanted to look at how good people find themselves doing bad things, how a culture can be shaped by secondary trauma, the trauma of witnessing. How it can sometimes be healed.

This is your third novel, and you’ve also published poetry and non-fiction – not to mention directed a film, or your first career in broadcast journalism. Do you simply move from one to another genre and practice, or does each idea or inspiration demand a different approach?

I’m not sure if that creative omnivory has helped or hurt whatever a person might call my career, but it’s actually just the way I move through the world. I attribute that to a rural upbringing, where a person’s greatest value was in being able to help out with whatever was asked of them. I found that in Newfoundland and Labrador, too. Artists rarely just did one thing. It was a partly matter of making a living, but I think it was also part of a regional temperament, if there is such a thing: curiosity in other people and places, a desire for surprise. All of that to say I don’t see myself as an expert in anything, rather as someone just really interested in how a single question can be addressed with many tools, yielding different outcomes. I aspire to be the kind of artist — and person — who asks questions in different ways and acquires the tools I need to do it. I’m a freelancer by nature, and a freelancer has to have a few tricks.

In your Notes you reference materials about the late 1960s culture and counterculture; could you expand on your research a little in terms for example of the settings of Wyoming and St John’s at that time?

I love a reader who reads the Notes! I have a guilty admission here. I’ve never been to Wyoming. Montana and North Dakota and Colorado but never made it to Wyoming. I really tried to get there during the writing, but: well, life. I need my main character to be American, and I picked Wyoming because I felt it was close enough to where I grew up in Alberta that I’d be able to skish together a believable kind of world. Montana had already made a guest appearance in a previous book, and I didn’t want to pick on it again.

St John’s I had a bit of a start on, having worked as a CBC reporter there 1998-2004. Six years of traipsing around asking people questions, trying to understand the historic context of stories I worked on, people I came to know and love helped. Then another eight years of medical work in Newfoundland doing much the same. Beyond that there was just a whole lot of reading: old newspaper articles, folklore publications. Old photos I found quite helpful, too.

On that point of research, I have to share this little funny [story]. Since the get-go, I’ve thought of this book as a work of historical fiction. It took place before I was born, and I needed to find primary and secondary sources to construct the story. That’s historical work, right? But recently I was talking to a writer older than me, and he asked about this historical fiction book I had coming out. I told him it was set in 1968-9 and he laughed out loud. “That’s historical?” he asked, in all seriousness. We had an interesting conversation then about what constitutes history. To me, what happened last week can be considered history. But does “historical” means it has to be old? What’s old? Is something only history if it happened before you were born? In that case, is one person’s historical fiction another person’s plain-old fiction? Interesting question to ponder over sushi. But my publisher considers it historical fiction, so I’ll stick with that.

I won’t spoil where the title comes from – but was that always the title?

Nope! For years the title was — wait for it — The Terrible Discipline of Her Face. (Really rolls off the tongue, doesn’t it?) I had written myself into a corner with the book when I realized an assumption I’d made about Vietnam war resisters — that they had to hide in Canada, and what better place to hide than a recently resettled outport? — was completely wrong. The plot I’d constructed was implausible. But there was something vital I wanted to say about finding oneself in Newfoundland for whatever reason and finding healing there. It was also at a time when I was questioning what I actually wanted to say about war. I absolutely did not want to glorify war, or write a story set in actual battles. I realized I really wanted to think and write about the people who carried all that secondary trauma, which in most cases was (is, will be forever) the women: the mothers, sisters, daughters, lovers of people who went to war, and every single Vietnamese woman whose life was upended or destroyed. A version of the story finally came together for me when I read Jimmy Breslin’s “A Death in Emergency Room One,” (New York Herald Tribune, Nov 24, 1963) about the attempted resuscitation of President Kennedy after he was shot, with its refrain (referring to Jacqueline Kennedy’s witness), The terrible discipline of her face. I can’t pretend to know what she was thinking in those moments, but finally I knew that what I was exploring with this book were the walls people build around trauma.

But during a major rewrite I undertook in the summer of 2024 under the guidance of my editor Kate Kennedy, I realized that my preoccupation with the war-time experiences of non-combatant women hadn’t really worked its way onto the page in a way I would have been proud of. The women are there, and they’re hurting (and surviving), but I had to admit the book was really still about James. Which was my original intention. I don’t think my previous novels did a great job at creating three-dimensional male characters, and I wanted to improve on that. So as much as I loved the original title, it had to go. (Breslin’s story still makes a cameo, though.)

The new title also allowed designer Beth Oberholtzer to come up with a very snazzy cover, so I’ll take that as a win!

The Crane is published by Breakwater Books.