Breaking the boundaries of the painting: a conversation with David Baltzer, Part Two

August 2023

You’ve presented a couple of pop-up exhibitions, with the Memetic-Self Portraits at the Neele Building in 2018 and most recently When Gravity Fails at the Arts and Culture Centre. Why do those?

It gets the work up, gets it on the walls, in a non-commercial space. I was able to get fifteen large pieces on the wall and just stand back and study the paintings and tryi to understand what I was trying to do and if I achieved it. In that sense it was good to move it out of the way and make room for [the new series].

What about the titular piece, When Gravity Fails? It’s such an intriguing composition, with all those floating circles.

That came out of one of my altarpiece ideas. The Diaspora Altarpiece. Bill Rose said I don’t normally like when you break the boundaries of the painting. But this one really works. That was nice.

Was it conceived that way?

Yeah. I built a panel. I had a nice bandsaw and I started cutting circles out of it. And then I reframed all of it with wood. I subtitled it things fall apart. It could have been subtitled entropy. The idea that unless you find some force that pulls things together, things fall apart. That’s the nature of the universe. I thought about my family. That is my grandfather’s family, he is fourteen or so when that shot was taken. The only person in that family that I have met is the little baby, Uncle Wesley. None of the others, they were just gone. And when my family moved from Michigan to California I lost connection with all the rest of my family. I never saw them again. I didn’t really know that I missed it until I moved here. Jennifer’s awash in her family. She sees them all the time. I don’t have that. I just don’t have that, those family bonds are not part of my DNA.

Can you tell us about your new series of paintings?

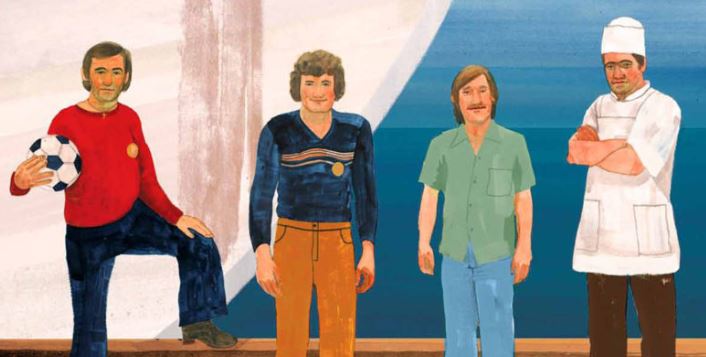

I did a couple of images in the Memetic series that I subtitled Child Of. Child of War, or Child of Conflict. Since I don’t have children I started thinking about childhood and the elements that form a person. Their roots. Essentially it’s called Origin Stories. They’re not real origin stories, they’re manufactured, created origin stories more to deal with psychological issues or cultural issues rather than personal issues. The genesis of it, I was driving cross-country once and somewhere in Tennessee I saw a moving truck that [was branded] So-and-So and Son’s moving company. And I started thinking about that fact that I don’t have children and I will never have children. And I thought, I’m an artist, I can create my own children. So I came back and started playing with compositive faces in photoshop, taking random faces – all of those have my face embedded in there with other faces. I have a collection of my faces through the years, that one was when I was 14, that one high school, that one my driver’s licence. I was surprised how easy it is to put three or four faces together and create a believable face. It isn’t a real person, it’s a combination.

When will we see this work?

Probably next year.

Can you name a visual artist that influences you, and a filmmaker that influences you?

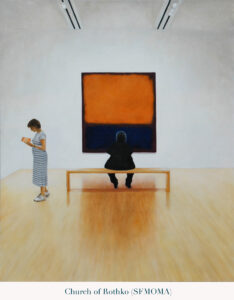

Early on I was very much influenced by Richard Diebenkorn. I went to his show in 2001 in San Francisco. Even though I don’t paint in any way like Mark Rothko I just love Mark Rothko. There’s a magic to his work. When I come to a museum with his work I just sit in front of it for as long as I can. [Diego] Velázquez. And filmmakers? I was very much drawn to Bergman when I was younger. Martin McDonagh, who wrote and directed The Banshees of Inisherin, and In Bruges.

Did you grow up in a house with a lot of art?

My dad drew for us, he drew pictures of things to entertain us. When I got to high school I took art classes but I didn’t draw very well. When I got to college, something clicked. But it didn’t stick with me because of a disgruntled art teacher*. It would be interesting to know how my life would have been different if I had stayed with painting. I was 20 years old and I was selling my work. [Soon]I was working in the semi-conductor industry as a test floor manager, and making a lot of money. And eventually I just said this is it I’m done.

*Who told Baltzer that painting was dead – see part one of this conversation.

Images: Underground Escalator, My Own Private Diaspora, Church of Rothko.

See more of Baltzer’s work here.