The Healers

December 2017

It’s winter now, but in mid-September we were still swimming in lakes in rural Quebec. One afternoon two friends and I took a day trip from Montreal to Rawdon. While I was in the water, swimming across Lac Rawdon, a few butterflies fluttered by, making me think of the spirits and ancestors who continuously surround us. Quebec’s wilderness reminds me of Newfoundland in a way, it’s something about the ruggedness and wildness of the trees. The water and mountain ranges echo the west coast of the Island.

My maternal grandfather, Robert Beattie, is from Quebec. He was orphaned, and reared by my great-grandmother Mary Beattie, a Bell telephone operator in Montreal. Years ago they had a cottage in the Laurentians on Lac-Connelly, less than an hour from Rawdon, and I think of my grandfather Beattie, who fell in love with a Bell Islander (they met in Toronto), wooed her with tickets to an Ella Fitzgerald concert; their union brought forth three daughters, five grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren.

While I was home in Newfoundland this past summer, I was given a copy of a series of graphic novels by David Alexander Robinson dubbed Tales from Shadow River, illustrated stories about Indigenous people (Highwater Press). The Healer: Mary Webb, retells the life of my paternal great-great-grandmother, Mary Webb, a Mi’kmaq healer and midwife to 700 babies around Bay St Georges on NL’s west coast.

There’s an honour and a surrealism seeing your ancestors depicted in print, especially when they are

Mary Webb. Image courtesy of author.

visually brought to life. I have only a single photo of Mary Webb : she is standing an overgrown field filled with fern, wildflowers and weeds, wearing a white apron and a scarf wrapped around her head. Her hands are near her womb, and she is looking directly into the camera. She’s a petite, fair-skinned, elderly woman with a spirited ease.

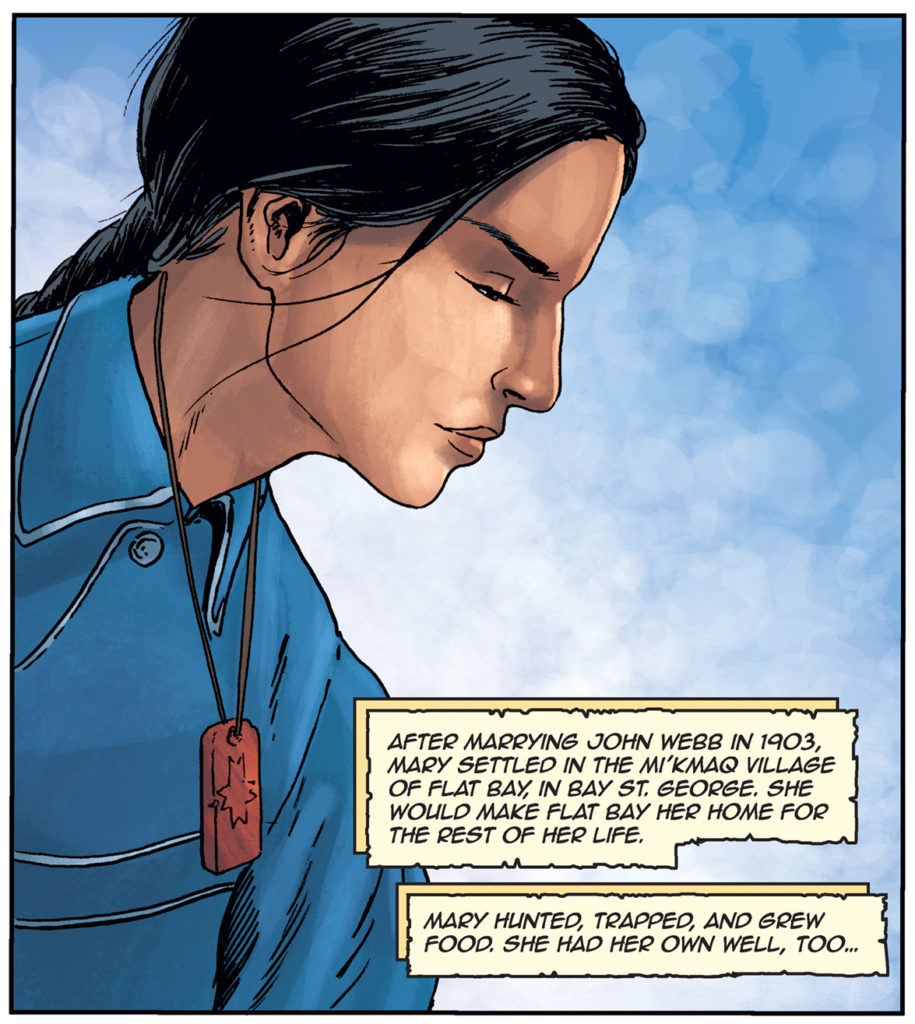

In The Healer, written by Robertson, a renowned mixed-Indigenous (Cree) artist, and llustrated by Scott B Henderson and colour artist Donovan Yaciuk, Mary Webb is much darker, with a long dark braid, and is dressed in more traditional Mi’kmaq dress. In fact, she looks like “a real Indian,” and nothing like her photograph. I wonder if this was a conscious choice, an attempt to make her more authentic. Another colonial construct to erase fair-skinned, blue-eyed Mi’kmaq, which is how the majority of my Aunties, Uncles, cousins, and ancestors, and certainly what my great-great-grandmother Mary Webb (Grammie, as my father calls her) actually looked like.

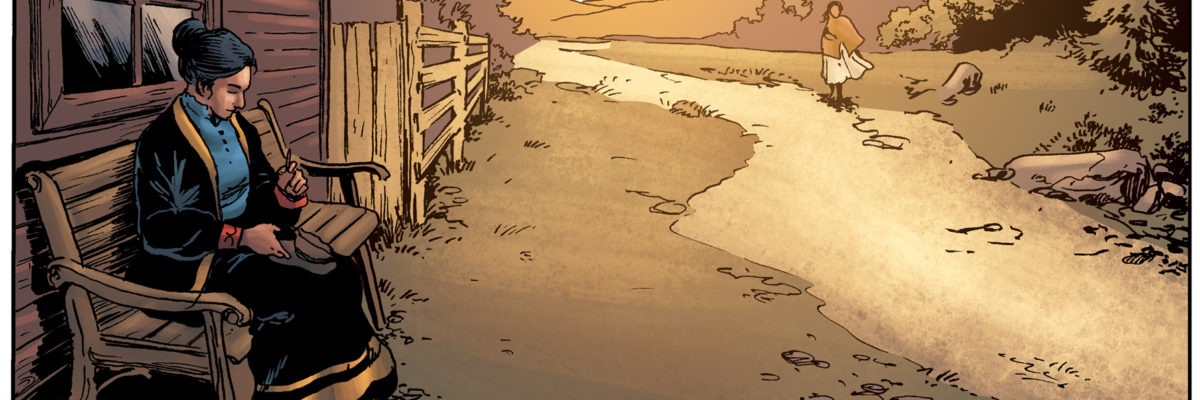

From The Healer: Mary Webb, by D.A. Robertson, illus. Scott Henderson, 2017. Reprinted by permission of HighWater Press

As The Healer portrays the story of her life : her birth in the Codroy Valley in 1891; her marriage to John Webb in 1903, which brought her to the Mi’kmaq village of Flat Bay, where she lived out her days hunting, trapping, growing food, and helping expectant mothers. She helped birth 700 babies, and not a single child died in her care. She’d travel for days by horse and sled, dog team, or snowshoe, and stay with the family for a week or more to make sure the mother and child were well. She tended to the meals and laundry to leave the mother to rest. Her first language was Mi’kmaw, but she learned English, French, and Gaelic in order to connect and communicate with the various families in the region.

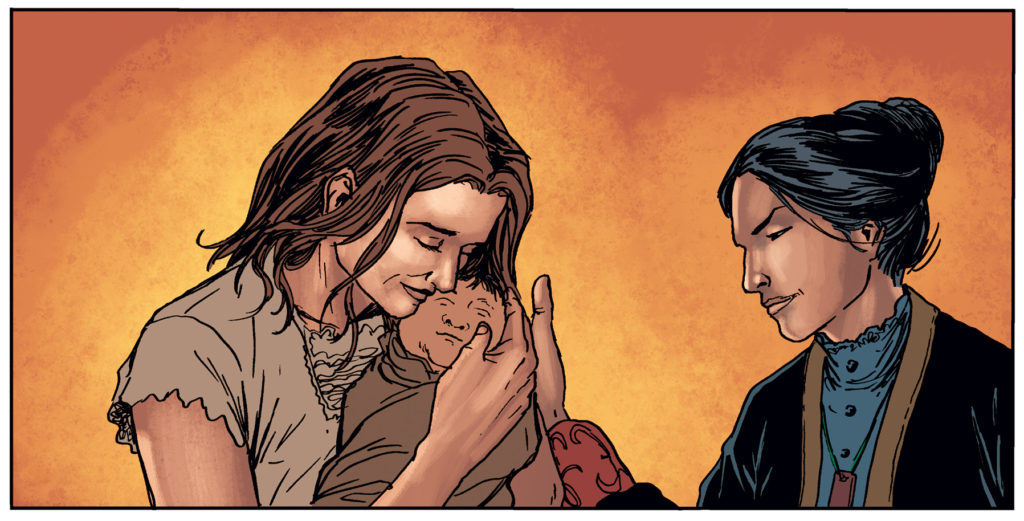

At one point in the book, during a difficult birth, she helps deliver a colicky baby, who upon arrival is instantly, almost magically, named Amelia. This brought me to tears, as Amelia is my maternal grandmother Beattie’s name, and my favourite. For years, I’ve said if I ever have a baby girl I am naming her Amelia, which translates to striving and industrious. In fact, my middle name is Leigh, a nickname for my grandmother.

I remember telling my grandmother Amelia about Mary Webb before she died, at age 78, four years ago on Fall Equinox. She was surprised, as she never heard tell of Mi’kmaq people in Newfoundland. Back when she was a girl, Indigenous people were called Jackatars, a pejorative Newfoundland term that refers to French and Mi’kmaq ancestry, which had connotations of being lazy promiscuous liars.

From The Healer: Mary Webb, by D.A. Robertson, illus. Scott Henderson, 2017. Reprinted by permission of HighWater Press

According to The Healer, Mary Webb also treated all sorts of people for various illnesses, and used traditional medicines to heal. She buried the placenta in the earth after childbirth, an offering to honour the remarkable organ that connects mothers to unborn baby in the womb. In 1930, Mary’s husband John Webb died, and she later found companionship with Norman Young. She remained in Flat Bay, and continued to heal people, and share Mi’kmaq culture and language. In 1978, aged 97, she got sick and was hospitalized, where the nurse cut off her braids, and she died on June 3, five years and four days before I was born.

Perhaps it’s alchemy, or a touch of ancestral wisdom, but reading The Healer embodied all my grandmothers in one form or another. Reading about my great-grandmother helping give birth to all these babies resonates and leaves me to question what it means if I choose not to have children. There are hours when I’ve felt certain I am not going to be a mother, yet the thought of never becoming a grandmother breaks my heart. I’d certainly never have been swimming in rural Quebec, where my great-grandmother spent time before the harvest, carrying one grandmother’s name, and honouring another grandmother’s medicines, if it weren’t for all the women who make up my grandmothers.