Decidedly disinterested in Oscar buzz (“I feel like life is the prize,” Alice Walker once said), the author told me that she hopes the film prompts viewers to embrace “The Gospel According to Shug.”

March 2024

In his early review of the epistolary novel that would later win the 1983 Pulitzer Prize in fiction, a New York book critic declared The Color Purple a work of “permanent importance.” “Alice Walker excels at making difficulties for herself and then transcending them,” noted Peter Prescott in Newsweek. “Her story begins at about the point that a respectable Greek tragedy reserves for its climax … then works its way toward acceptance, serenity, and joy.”

Set in segregated Georgia, the novel traces the life of Celie Johnson, a Black, sexually exploited teenager who, in an effort to understand her plight, writes letters to God.

I’ve been reflecting on Prescott’s praise for the book that brought Walker global acclaim (she was the first Black woman awarded a Pulitzer for prose) since the announcement of the 2024 Oscar nominations. For The Color Purple musical movie, a highly touted, reportedly $100 million film version of the Broadway musical first staged in 2005, received only a single Oscar nod.

The Broadway production was, itself, a re-imaging of the 1985 movie (directed by Steven Spielberg) that was based on Walker’s landmark release.

“I’m very humbled by it … but I did not get here on my own,” Danielle Brooks told The Hollywood Reporter about her best supporting actress nomination for her role as Sofia. The feisty character was inspired, in part, by Walker’s mother who refused to be controlled by anyone.

Brooks continued: “I’m hoping that we can garner a win for the efforts of everybody that was a part of this beautiful production.”

Among the producers for the movie, Oprah Winfrey wore a dazzling array of purple outfits during the marketing campaign for the film. Like Brooks, Winfrey had also received a best supporting actress nomination for her portrayal of Sofia in the 1985 Spielberg movie. Angelica Huston took home the golden statuette for her role in Prizzi’s Honor.

Shortly before the release of the musical movie on Christmas Day 2023, I visited with Alice Walker, now 80, in her cozy northern California home. Decidedly disinterested in Oscar buzz (“I feel like life is the prize,” she once said), the author told me that she hopes the film prompts viewers to embrace “The Gospel According to Shug.”

By that, she meant a passage from her novel in which the singer Shug Avery (played by Taraji P Henson in the new movie) extols nature as she walks through a flower-filled meadow with a beleaguered Celie (played by Fantasia Barrino). Unapologetically bisexual, Shug — the name suggests sweetness — has initiated a romance with Celie that has slowly helped her endure an abusive marriage. Shug also sleeps with Celie’s anguished husband, Mister (played by Colman Domingo).

“I think it pisses God off if you walk past the color purple in a field somewhere and don’t notice it,” Shug tells Celie. “People think pleasing God is all God care about. But any fool living in the world can see it always trying to please us back. … Everything want to be loved.”

Readers will find an expansion of Shug’s Gospel in Alice’s subsequent novel, The Temple of My Familiar (1989).

As the official biographer of Alice Walker, I spent nearly a decade researching the art and activism of a writer whose signature work has sold more than five million copies and been translated into more than thirty languages. Moreover, The Color Purple sparked (and continues to provoke) vital conversations about race, domestic violence, gender, and sexuality in both the literary and public arenas.

Indeed, I was prompted to ask Alice to grant me permission to document her life after I witnessed her transform an insult (in my view) that she’d suffered at a posh reception into a paean to the dispossessed. The incident took place after Alice had read from and discussed the impetus for her novel Possessing the Secret of Joy (1992) which details the physical and emotional pain an African woman suffers after undergoing female genital mutilation (FGM).

By way of explaining the procedure, Alice had mentioned the words vagina and clitoris in her remarks. Allegedly speaking on behalf of guests who’d been “offended” by the words, a woman at the reception heatedly asked Alice for “advice” on how to address their expected complaints.

As I wrote in the early pages of my book, Alice Walker: A Life: “What was it … about [the author] and her work that always seemed to generate such intense emotion?”

In determined pursuit of answers, I interviewed (among others), Alice’s first-grade teacher in her rural birthplace, Eatonton, Georgia; the Japanese translator of The Color Purple, in Tokyo; admirers of Alice’s books in Cuba; an HIV positive woman from Uganda who, at a health conference in Brazil, told me (with tears in her eyes) that Alice’s stance against FGM gave her hope.

Marching on, I connected with Alice’s “rainbow coalition” of lovers. I snacked on cashews with her brother Bill and later accompanied Alice to his funeral in Boston. I helped Alice’s sister Ruth find dry ice when a blackout in Atlanta imperiled the hams she’d stockpiled in her freezers.

During a trip to Molokai to research Alice’s support of traditional Hawaiian healers, I was chased by wild moa kāne (roosters). I savoured Thai coconut soup with one of Alice’s literary peers (herself a celebrated Black poet, now deceased) who tried but could not conceal her envy of the author’s ascent.

Strolling with Alice’s nephew under a canopy of pecan trees near the Georgia homestead of Flannery O’Connor (read O’Connor’s story “Everything That Rises Must Converge”), I was stopped in my tracks when the young man declared: “Auntie Alice sees more out of one eye than most people see out of two.”

His reference was to the incident (detailed in Alice’s essay “Beauty: When the Other Dancer is the Self”) that left her, then age eight, permanently blinded in her right eye.

Forty-two years after the publication of The Color Purple and two decades after the release of Alice Walker: A Life —a narrative for which the subject did not request manuscript approval — precious memories, as the gospel song goes, ever flood my soul.

I enjoyed the musical movie. However, in the midst of the 2024 Oscar noise, I find myself revisiting an experience at a California eatery. My book was finally finished and Alice was soon to depart on a trip with a friend who’d taken the subway from her home, about 22 kilometers away, to join us, for dinner.

We were three women of colour who’d thoroughly reveled in each other’s company. Ditto for the “sisterly” attention of our server who bore a striking resemblance to author James Baldwin. Among the last guests to leave, we’d effectively closed down the joint.

Both Alice and I had driven to the restaurant that was near our then respective homes. But mass transit didn’t operate 24 hours in our locale. As none of us knew if the trains were still running, the woman who’d “come from away” was uncertain about how she’d make it home. Uber had not yet become a thing.

We’d been standing on the sidewalk for several minutes pondering the dilemma when Alice thrust a hand into her pants pocket and pulled out a wad of cash. Offering it to the woman, she said: “Take a cab.” Stunned, the woman immediately declined. “Thanks, but I could never,” she replied.

Alice stood pat with her outstretched hand. “Take it,” she insisted. The woman still refused. They went back and forth a couple more times. Finally, Alice, with the gentle southern lilt that remains in her voice, quietly said, with real feeling: “I know what money is for.”

With that, the woman peeled off several bills from Alice’s stash and I drove her to a nearby taxi stand. As with the exchange I’d witnessed at the high-toned reception, I knew that I’d been gifted, yet again, with a powerful image of Alice Walker in loving service to the health and safety of the most vulnerable in society.

In today’s Canadian dollars, the cab fare would have been about $130.

Upon arrival home, I replayed the scene outside of the restaurant, in my mind. “If I ever meet someone who wants to write another biography of Alice, I’ve got the perfect beginning,” I thought to myself and smiled.

Consider it free for the taking.

The 2024 Oscars will be broadcast March 10.

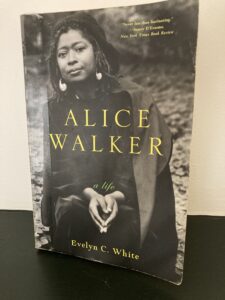

Evelyn C White is a journalist in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She has been widely published in Canada and the US.

(Photo: the author, left, and her partner, Joanne, at a screening in Oakland, CA.)